Top Articles I've Read in 2018

∷

Books: 2024 - 2023 - 2022 - 2021 - 2020 - 2019 - 2018

Here are the top eleven papers I’ve come across in 2018.$^*$ These papers are mostly recent publications (within the last two years) with some older ones peppered in. They are in chronological order below.

Pick the Largest Number

Author: Thomas Cover

Publication: Open Problems in Communication and Computation

Published: 1987

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4808-8

This short note describes a solution to the two-card variant of a game called Googol. In this variant of the game, Player 1 writes down two distinct rational numbers $x_1, x_2$ and Player 2 guesses which of the two is larger after seeing the first number $x_1$. The principle of indifference gives a probability of success of one half by random guessing. The paper offers a strictly better solution. Pick a threshold $T$ from density $f(t)$ where $f(t)$ has support on the reals, e.g., the standard normal distribution. If $x_1 < T$, then say $x_2$ is larger and vice versa. Since there is a non-zero probability that $T$ is between $x_1$ and $x_2$, this strategy strictly dominates random guessing.

On a first reading, this is an unexpected result that took a bit to wrap my mind around. Note that this conclusion does not violate the principle of indifference since Player 2 is not in a state of ignorance; they have observed the value of $x_1$. What makes this problem interesting is that $x_2$ does not depend on the value of $x_1$ so knowing $x_1$ seems irrelevant to determining the size of $x_2$.

I came across this paper by way of the Fermat’s Library Journal Club.

The Trouble with Psychological Darwinism

Author: Jerry Fodor

Publication: London Review of Books

Published: Jan 1998

Link: www.lrb.co.uk/v20/n02/jerry-fodor/the-trouble-with-psychological-darwinism

Jerry Fodor reviews “How the Mind Works” by Stephen Pinker and “Evolution in Mind” by Henry Plotkin. These thinkers fall in line with the New Rationalism view of the mind which holds that the mind functions from modular structures and is partly innate (or the structures are anyway). This is in contrast to the blank-slate, social constructionist, plastic empiricist view. Fodor lays out four principles of Pinker’s and Plotkin’s views and points out where they deviate from his own. Here are the four: 1. the mind is a computational system; 2. the mind is largely modular; 3. a lot of cognitive structure is innate; 4. a lot of mental structure is an evolutionary adaption. Fodor contests the fourth point by adding that 3. doesn’t imply 4.

A wonderful read that I couldn’t endorse more. Fodor’s writing is both lucid and highly entertaining. Here is a passage characteristic of this:

“Psychological Darwinism is a kind of conspiracy theory; that is, it explains behaviour by imputing an interest (viz in the proliferation of the genome) that the agent of the behaviour does not acknowledge. When literal conspiracies are alleged, duplicity is generally part of the charge: ‘He wasn’t making confetti; he was shredding the evidence. He did X in aid of Y, and then he lied about his motive.’ But in the kind of conspiracy theories psychologists like best, the motive is supposed to be inaccessible even to the agent, who is thus perfectly sincere in denying the imputation. In the extreme case, it’s hardly even the agent to whom the motive is attributed. Freudian explanations provide a familiar example: What seemed to be merely Jones’s slip of the tongue was the unconscious expression of a libidinous impulse. But not Jones’s libidinous impulse, really; one that his Id had on his behalf. Likewise, for the psychological Darwinist: what seemed to be your, after all, unsurprising interest in your child’s well-being turns out to be your genes’ conspiracy to propagate themselves. Not your conspiracy, notice, but theirs.”

Jerry Fodor passed away in late 2017.

A Mathematician’s Lament

Author: Paul Lockhart

Published: 2002

Link: http://mysite.science.uottawa.ca/mnewman/LockhartsLament.pdf

This essay is an indictment of the modern K-12 math curriculum primarily because mathematics is presented as unmotivated, algorithmic drudgery by educators who have never done mathematics. This is a wonderful and hilarious read! The author argues that mathematics classes should be less structured, more argument based, and concepts and distinctions should be situated in their historical and philosophical context.

The author runs with the analogy of painting where we would never teach painting without having the students actually paint. The proper analogue with the current mathematics curriculum would be having the students memorize colors, brushes, styles, and terse terminology with no motivation or context and not ever really have them paint except in some rigidly defined sense, e.g., painting by numbers or tracing from a stencil.

The view is pushed that mathematics is an art whose practical consequences are a biproduct rather than an end. This is similar to those who argue that philosophy is an activity rather than a subject.

To Explain or to Predict

Author: Galit Shmueli

Publication: Statistical Science

Published: Aug 2010

DOI: 10.1214/10-STS330

This paper covers the difference between prediction and explanation in depth. It discusses the difference in the modeling process from conception to model validation featuring two case studies with the Netflix Challenge data and auction data. The author distinguishes descriptive modeling from the tasks of prediction and explanation; however, descriptive modeling is not covered in depth.

While this paper is not groundbreaking, it provides an excellent overview between different sorts of modeling especially for those coming from machine learning-heavy or statistics-heavy backgrounds. The appendix provides an example of when a properly specified model, i.e., the true model, may not be the most predictive. Though counterintuitive at first, this result demonstrates the fundamental difference between the tasks of prediction and explanation.

Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on

Authors: Benjamin Djulbegovic & Gordon H Guyatt

Publication: The Lancet

Published: Feb 2017

DOI: doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31592-6

This article introduces Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) and it’s three main tenets: 1. not all evidence is created equal; 2. all relevant evidence should be used in decision making; 3. clinical decision making should consider patients’ values and preferences. Initially, the field pushed for practitioners to remain up-to-date on the latest research in their field; however, this is too tall of a task, so the movement changed emphasis to systematic studies and literature overviews.

One prominent criticism addressed is that this leads to algorithmic decision making that is divorced from the human element. This is true is two respects: 1. the reasoning may be too complex for the patient to understand; 2. the individual practitioner’s influence is greatly reduced.

I found this paper particularly interesting given that there’s an close analogy between EBM and data science that would have not been apparent prior to working in industry.

This paper was featured in the EBM column of an issue of The Reasoner.

Understanding Deep Learning Requires Rethinking Generalization

Authors: Chiyuan Zhang, Samy Bengio, Moritz Hardt, Benjamin Recht, & Oriol Vinyals

Publication: arXiv

Published: Feb 2017

Link: arxiv.org/abs/1611.03530

In this paper, the authors present empirical and theoretical results on generalization error and the capacity for memorization in deep learning models, specifically with convolutional neural networks (CNN). CNN architectures exist that achieve near-perfect performance on standard image datasets, e.g. CIFAR10, with low generalization error. The authors found that by randomly permuting the image labels, the same architectures produce models with near-perfect accuracy on the training data but, correspondingly, a high generalization error. They summarize their finding as follows:

Deep neural networks easily fit random labels.

To put this result into context, the authors explore how different regularization techniques, e.g., dropout, weight decay, etc., affect generalization error. The conclusion is along the lines of we don’t know what causes neural networks to generalize well. I do want to emphasize that while I found this paper interesting, readable, and helpful to understanding deep learning models, it may have received more hype from the ML community than it deserves.

I crossed paths with this paper while browsing the morning paper.

Stuck! The Law and Economics of Residential Stability

Author: David Schleicher

Publication: Yale Law Journal

Published: October 2017

Link: https://www.yalelawjournal.org/article/stuck-the-law-and-economics-of-residential-stagnation

This article discusses the phenomena of declining interstate mobility and some of its potential causes and effects. To summarize the decline:

Americans are not leaving places hit by economic crises, resulting in unemployment rates and low wages that linger in these areas for decades. And people are not moving to rich regions where the highest wages are available.

The author examines the state and local policies that affect interstate mobility both those that impede entering a new state, e.g., differential licensure requirements, and those that impede leaving one’s current state, e.g., encouraging homeownership through the mortgage interest deduction and other subsidies. One effect discussed extensively of the sluggish labor market resulting from decreased interstate mobility is the decreased effectiveness of federal macroeconomic policy. Consider two neighboring states where one state is booming while the other busts but there is little population movement between the states. In this case, there may not be a uniform monetary policy beneficial to both states.

This article is interesting primarily as a dip of one’s toes into the depths of economic mobility.

I came across this article in the Further Reading from the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

TOP5ITIS

Author: Roberto Serrano

Status: Working paper as of Jan 2018

Link: www.econ.brown.edu/Faculty/serrano/pdfs/wp2018-2-Top5itis.pdf

This paper is a commical commentary on both the academic economists’ infatuation with the Top5 economics journals and the recent discussions of them at the AEA meetings. The author charges the practice of focusing primairly on Top5 publications as arbitrary gatekeeping that potentially stifles innovation that is not clearly a good measure of either one’s performance as an academic or one’s expertise in a topic. A sample of the goodness:

Since the disease is a simple application of the counting measure (typically a person learns to count in primary school), through a process of contagion, top5itis spreads quickly to affect people outside economics, including schoolchildren offspring of economists who get together in the playground to make disparaging remarks about each other’s parents.

Learning is a Risky Business

Author: Wayne C. Myrvold

Publication: Erkenntnis

Published: Feb 2018

DOI: 10.1007/s10670-018-9972-0

This paper advances an argument against the principle of indifference. Roughly, the principle of indifference says that absent evidence to the contrary one should assign equal probability to each possible state of the world. The author’s argument proceeds by introducing time into the partitioning of the state space. Simply put: consider a year where each day either $\phi$ or $\neg \phi$. Then there are $2^{365}$ possible histories. The principle of indifference assigns equal probability to each; however, this implies that the assessment of probabilities on each day is independent of what happened on prior days, i.e., one does not learn from experience.

It’s a compelling argument that may require the notion of learn to be tightened up. Also: the paper’s leading example involves a SuperBaby.

Anchors: High-Precision Model-Agnostic Explanations

Authors: Marco Túlio Ribeiro, Sameer Singh, & Carlos Guestrin

Publication: Proceedings of The Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-18)

Published: Feb 2018

Link: https://aaai.org/ocs/index.php/AAAI/AAAI18/paper/view/16982

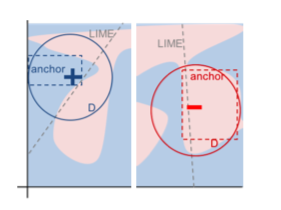

This paper introduces an approach to prediction explanation called anchors as a refinement of the LIME approach. With LIME, model behavior is assessed by sampling points around the observation of interest and building an interpretable model on the sampled data to find out which variables are driving the prediction. More on LIME here. One difficulty with building local models for post-hoc prediction is that it is not clear how far out from the observation of interest that the local model generalizes. This concern is addressed by introducing anchors, topologically simple regions of the feature space where a prediction holds with high probability. Think of anchors as a sufficiency condition. This method can better generalize because it is essentially claiming less. Note that at present the anchor approach only works with binary classification models.

The GitHub repo to test out these techniques can be found here.

Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials

Authors: Angus Deaton and Nancy Cartwright

Publication: Social Science & Medicine

Published: Aug 2018

DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.005

This article evaluates the benefits and limitations of randomized control trials (RCT). In practice, the goal of running an RCT is to obtain an estimate of the average effect from some treatment employing as few assumptions as possible; indeed, estimating the average treatment effect (ATE) is a nonparametric method. We often think of an RCT is the “gold-standard” evidence for the existence of a causal effect in medicine, economics, etc.; however, the effectiveness of an RCT comes from having no prior evidence. If we have more information about the underlying causal mechanism, then we can perform more accurate inference by stratifying our randomization by causal pathways, for instance, or employ various other causal modeling techniques. The value of RCTs is in when we do not have the same assumptions; however, once we agree on assumptions, we can leverage those assumptions to use other estimation methods.

Applying the results of an RCT is tricky. Generalizing from a sample to a population is suspect in the social sciences due to all of the potential differences between groups, e.g., the sample may not have been random or there may be been post-randomization confounding, also called realized confounding. Often the estimated ATE is applied to the individual; however, this is entirely erroneous, since the ATE is an average and an individual’s characteristics will differ from the average.

“In these conversations, the results of an RCT may have marginal value. If your physician tells you that she endorses evidence-based medicine, and that the drug will work for you because an RCT has shown that ‘it works’, it is time to find a physician who knows that you and the average are not the same.”

See here for comments on this paper from Judea Pearl.

$^*$Since we’re likely not Pythagoreans, there’s probably not a good reason for preferring ten articles to eleven.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee