Top Articles I've Read in 2019

∷

Books: 2025 - 2024 - 2023 - 2022 - 2021 - 2020 - 2019 - 2018

Below are the top eleven articles I’ve read in 2019. A theme of methodology runs through this set of papers, especially statistical methodology. There’s also some fun miscellany mixed in with blockchain (whose craze seems like a lifetime ago now), unicorns, and the history of the English language. To my surprise, all of these articles are from the present decade. They are presented in chronological order.

The Credibility Revolution in Empirical Economics: How Better Research Design Is Taking the Con out of Econometrics

Authors: Joshua D. Angrist and Jörn-Steffen Pischke

Publication: Journal of Economic Perspectives

Published: Spring 2010

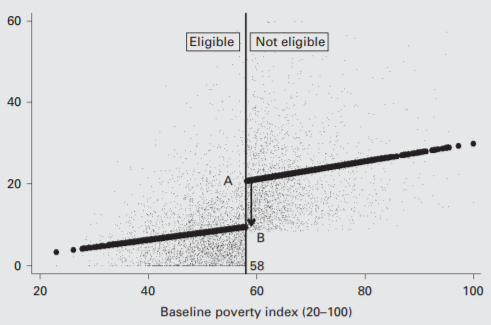

DOI: 10.1257/jep.24.2.3

This paper is in some sense a response to Ed Leamer’s 1983 Let’s Take the Con Out of Econometrics that questioned the methods of econometrics both in theory and in practice for parading as objective science when in reality several hidden judgements are made by practitioners. Angrist and Pischke argue that, since Leamer’s critique, a focus on research design, i.e., the way in which studies are formulated and data is collected, has led to a revolution in econometrics. Specifically, the use of quasi-experimental methods such as instrumental variables, regression discontinuity design, and difference-in-differences has led to more robust estimates of causal effects. Whereas Leamer proposed sensitivity analysis as a solution, the authors contend that better design better addresses Leamer’s worries.

Angrist and Pischke give several examples with a focus on applied microeconomics, specifically labor and education, since these fields adapt easily to the quasi-experimental methodology. This paper sheds light on the current practice of econometrics, or at least how one influential party sees it. The authors remark that these methods may not be sexy or directly and quickly get at the “big” questions, but the quasi-experimental approach to econometrics proceeds by accumulation and small gains in understanding, similar to how we think about the hard sciences.

This paper gives one a nice introduction to the ideas and context of Angrist and Pischke’s text Mostly Harmless Econometrics or their more friendly Mastering ‘Metrics.

English is not normal

Author: John McWhorter

Publication: Aeon

Published: Nov 2015

Link: aeon.co/essays/why-is-english-so-weirdly-different-from-other-languages

This is a quirky essay about the history of the English language. The author argues its unique place among languages is largely an artifact of history. Here are two interesting tidbits. For the first, Old English is basically unrecognizable from contemporary English; witness the following: “Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon” is Old English for “So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore”. While that sentence seems a bit contrived, you get the point. For the second tidbit, over time, English adopted French and Latin words along with a natural scale of refinement and formality: for example, kingly (English), royal (French), regal (Latin) all denote the same idea but express it with increasing regard.

The author leaves us with this summary:

“The common idea that English dominates the world because it is ‘flexible’ implies that there have been languages that failed to catch on beyond their tribe because they were mysteriously rigid. I am not aware of any such languages. What English does have on other tongues is that it is deeply peculiar in the structural sense. And it became peculiar because of the slings and arrows – as well as caprices – of outrageous history.”

The Need for Cognitive Science in Methodology

Author: Sander Greenland

Publication: American Journal of Epidemiology

Published: Aug 2017

DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwx259

There has been much recent literature on the deficiency of current statistical methods; however, not much attention has been paid to cognitive biases of practitioners using these methods. Greenland describes three such biases:

1) dichotomania, the compulsion to perceive quantities as dichotomous even when dichotomization is unnecessary and misleading, as in inferences based on whether a P value is “statistically significant”; 2) nullism, the tendency to privilege the hypothesis of no difference or no effect when there is no scientific basis for doing so, as when testing only the null hypothesis; and 3) statistical reification, treating hypothetical data distributions and statistical models as if they reflect known physical laws rather than speculative assumptions for thought experiments.

While these points have been brought up by Gelman and others in some form, Greenland provides a cohesive and convincing account of when it is that the tools themselves aren’t the (only) problem. He argues in favor of the methodological position that “Statistical analyses are merely thought experiments, informing us as to what would follow deductively under their assumptions” (Gelman agrees). While an interesting philosophical position (and one have sympathies for), this view certainly doesn’t match my experience with how practitioners treat statistical analyses in the wild. Perhaps, that’s additional evidence that we ought to be thinking about the cognitive status of practitioners.

Amusing quotes are peppered throughout: “This null obsession is the most destructive pseudoscientific gift that conventional statistics (both frequentist and Bayesian) has given the modern world.”

Greenland also takes a swipe at formal methodology and philosophy of science: “thinking that parsimony is a property of nature when it is instead only an effective learning heuristic, or that refutationism involves believing hypotheses until they are falsified, when instead it involves never asserting a hypothesis is true”. While I buy much of what Greenland has to say, I may be too much of an ideologue to go this far.

Blockchain is not only crappy technology but a bad vision for the future

Author: Kai Stinchcombe

Published: Apr 2018

This is a followup to Ten years in, nobody has come up with a use for blockchain. The author argues two points: people often confuse blockchain the idea with blockchain the technology; and we actually do not want fully trustless transactions. On the first point, people want a way for correct information to be entered into a tamperproof database, e.g., tracking fruit to ensure it’s organic; however, nothing stops bad data from being entered into the database. On the second point, the author defends the value of social trust and points out examples where even major uses of cryptocurrencies, e.g., the Silk Road and Ripple, rely on trust measures, e.g., seller reviews, rather than smart contracts or anything else of the sort. These social institutions are better than having to trust the code of someone offering a smart contract or from having to write one’s contract every time one wishes to make a transaction. Trading this trust for other ends leads to a world that’s “not a paradise but a crypto-medieval hellhole.”

Why Data is Never Raw

Author: Nick Barrowman

Publication: The New Atlantis

Published: Summer/Fall 2018

Link: www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/why-data-is-never-raw

This article applies the idea of theory-ladeness of observation from the philosophy of science to the idea of raw data in statistics and data science. Just as the presuppositions of an observer affect how one interprets what is observed, how data are captured (not just given) affect what the data say.

“For example, rates of domestic violence were historically underestimated because these crimes were rarely documented. Polling data may miss people who are homeless or institutionalized, and if marginalized people are incompletely represented by opinion polls, the results may be skewed. Data sets often preferentially include people who are more easily reached or more likely to respond.”

For this reason, the method of data acquisition is highly relevant to its interpretation and use whether for survey data from such and such a population, measurements in a lab, or transaction logs from a production system. To sum up, the author offers the words of Geoffrey Bowker of UC Irvine: “Raw data is both an oxymoron and a bad idea; to the contrary, data should be cooked with care.”

The Bias Bias in Behavioral Economics

Author: Gerd Gigerenzer

Publication: Review of Behavioral Economics

Published: Dec 2018

DOI: 10.1561/105.00000092

This article is an attack on the current state of behavioral economics. Since the work of Kahneman and Tverksy in the 1970s, behavioral economics has largely focused on the identification of biases and heuristics for decision making. Biases are consistent and widespread departures from the rational choice model. The author argues for the bias bias: attributing a bias to behavior that is potentially well-motivated.

The most interesting bias discussed is the law of small numbers: “People think a string is more likely the closer the number of heads and tails corresponds to the underlying equal probabilities. For instance, the string HHHHHT is deemed more likely than HHHHHH.” When we consider six coin flips, this intuition is clearly incorrect since each possible outcome is equally likely and the events are independent. Consider, instead, if there are seven coin flips. We still have that all outcomes are equally likely; however, HHHHHT appears as a substring in four outcomes, while HHHHHH only appears in three. This result holds for any number of coin flips greater than the length of the substring. This potentially explains people’s otherwise confused intuitions.

The paper concludes by suggesting that behavioral economics abandon its current research program and follow the alternative bounded rationality vision set out by Herbert Simon in the latter half of the 20th century. Rather than focusing on departures from the expected utility model, Simon focused more on descriptive models and included notions of choice under uncertainty rather than exclusively choice under risk.

Intellectual Control

Author: George Fairbanks

Publication: IEEE Software

Published: Jan/Feb 2019

This article is about the notion of control in software development. The current practice of test driven development provides statistical control, i.e., if all of the test cases pass, then there likely is not a problem. In contrast, an alternative notion is intellectual control, i.e., being able to explain what the code/program/system is doing. There are obvious tradeoffs: intellectual control doesn’t scale well; statistical control can be effective if executed well; etc.

The author provides an effective analogy that differentiates the two notions of control:

“imagine driving a car on a road with guardrails. In this metaphor, the guardrails are tests and driving the car is us writing programs. He then wondered if it’s OK to successfully arrive at our destination after hitting the guardrails during the journey. His audience laughed because having a car under control means we are able to drive without hitting the rails.”

Tony Hoare said it best in his Turing Award lecture, “There are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies, and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.”

Unicorns, Cheshire cats, and the new dilemmas of entrepreneurial finance

Authors: Martin Kenney and John Zysman

Publication: Venture Capital

Published: Mar 2019

DOI: 10.1080/13691066.2018.1517430

This paper examines the rise of the unicorn: a start-up with a private valuation of over one billion USD. Many of these unicorns came about due to the low barrier to entry of starting a firm and raising capital. Often these firms are technology-focused with lots of intangible assets, e.g., Uber, AirBnB, etc., and are, thus, easily scalable. To scale up and gain market share, these companies often burn through massive amounts of capital while in a growth-phase. An ecosystem of funding, including traditional VC, angel investors, incubators, etc., has developed to progress these firms through their growth-phase with the eventual goal of selling their stake to another investor or to the public.

A result is that incumbent firms in traditionally stable industries have been “disrupted” by growth-phase start-ups aiming to take market share. The attempt to capture market share is often done by offering lower prices, e.g., an Uber or Lyft ride is usually cheaper than getting a taxi. At the same time, the start-up is using capital money to fund this behavior. The fight for market share is motivated by the winner-takes-all nature of many industries, since there is not necessarily an market need for several search engines, social media platforms, etc.

From an economic perspective, it is not clear if this method of producing firms is beneficial overall, since the goal for investors appears to be to raise the private valuation to sell to another investor or the public without concern for the long-term stability of the start-up.

The authors provide a nice summary for their paper’s goal: “to interrogate the enthusiasm for backing entrepreneurial start-ups, losses or not, and for seeking to turbo-charge their growth to the point that they become the so-called ‘unicorns.’”

This paper shared much in common with Capitalism without Capital which made the 2019 Top Books list. I came across this paper from an article in The Economist.

A New Americanism

Author: Jill Lepore

Publication: Foreign Affairs

Published: Mar/Apr 2019

Link: www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2019-02-05/new-americanism-nationalism-jill-lepore

This short article argues that nations look to an origin story to explain their existence and that this story changes with the times. It wasn’t until the 1840s that the people of the United States viewed themselves as a nation (not sure what population this applies to). These shared myths continued to be developed until the second half of the twentieth century where they fell out of fashion for historians as nationalism yielded way to globalization, first politically then economically.

Just because academic trends changed does not entail that the nation no longer looks for its founding myth; rather, these myths are just not provided by historians. The author alludes to this being the origin of the nativist, so-called nationalist movement observed in the US as well as in other countries. The author urges historians to write about the nation once more.

Lepore’s history of the United States These Truths was released in late 2018.

The Dangers of Post-hoc Interpretability: Unjustified Counterfactual Explanations

Authors: Thibault Laugel, Marie-Jeanne Lesot, Christophe Marsala, Xavier Renard, and Marcin Detyniecki

Publication: Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-19)

Published: Jul 2019

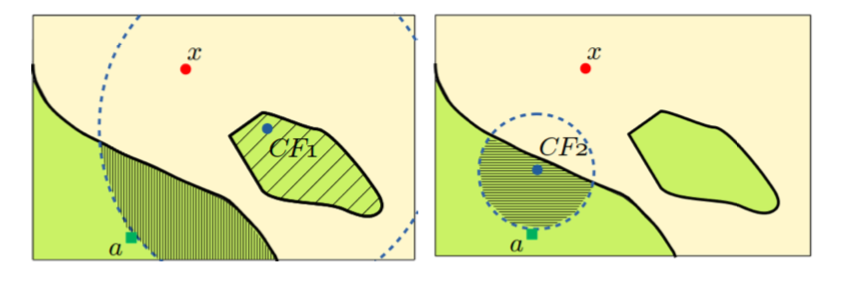

Link: ijcai.org/proceedings/2019/0388.pdf

This paper extends the idea of a local explanation of a classifier’s prediction to counterfactually-justified local explanations to provide a link between the classifier and the training data. For an explanation to be justified for a given point in the feature space $x$, there must exist point $z$ in the training data, perhaps the nearest point to $x$, that’s correctly classified where $x, z$ belong to the same label and are topologically path connected with respect to the euclidean topology on the feature space. The intuition is that a local explanation for a prediction cannot be justified in this stronger sense if the point in question is isolated from correctly predicted instances in the training data. This leads to the amusing corollary that no explanations are justified if the predictive model classifies all instances in the training data incorrectly.

The authors operationalize this through an approximation algorithm to provide an estimate of whether or not a point is path connected to a correct prediction of an observation in the training data sharing the same label. A followup paper by this group appeared at KDD in August.

I find this paper particularly compelling since it connects closely with my work studying the topological properties of explanations of classifier predictions.

Mistaken: I think, therefore I make mistakes and change my mind

Author: Daniel Ward

Publication: Aeon

Published: Oct 2019

Link: aeon.co/essays/i-think-therefore-i-make-mistakes-and-change-my-mind

This article is about the notion of human infallibility and how it is antithetical to rationality. On this conception, being rational is being able to give reasons for one’s actions and that involves the possibility of error. The author argues that the notion of human infallibility underlies both moral relativism in anthropology/sociology and revealed preference in economics, both of which the author finds objectionable.

The case of revealed preference is the more interesting of the two. Revealed preference is the notion that an agent reveals their preferences for goods through their choices, a behaviorist approach to choice/decision theory. The author argues that this theory does not account for genuine mistakes. We may think that is because the agent in the model is more rational than humans; however, this turns on the specific notion of rationality. On the reason giving account, mistakes are the hallmark of rationality.

“To err is human. Missteps, misapprehensions, misspeakings, momentary lapses and mess-ups are part of the fabric of life. Yet we are capable of making mistakes precisely because we are thoughtful, intelligent beings with complex goals and sincerely held values. We wouldn’t be able to if we were otherwise. Regrets: we’ve had a few. But we are the wiser for them.”

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee