Economic Methodology Meets Interpretable Machine Learning - Part I - Interpretability, Explainability, and Black Boxes

In this series of posts, we will develop an analogy between the realistic assumptions debate in economic methodology and the current discussion over interpretability when using machine learning models in the wild. While this connection may seem fuzzy at first, the past seventy years or so of economic methodology offers many lessons for machine learning theorists and practitioners to avoid analysis paralysis and make progress on the interpretability issue - one way or the other.

This post is the first entry in Economic Methodology Meets Interpretable Machine Learning and briefly introduces the ideas of black boxes, explainability, and interpretability for machine learning models and offers arguments for and against deploying only interpretable models in the wild when interpretable models are available. The debate over interpretable models in machine learning is far from settled and has been getting much attention in recent years.

There is no clear consensus on what exactly black boxes, explainability, and interpretability mean as evidenced by (and despite) the dozens of review articles (that are hopefully not all saying the same thing). See here, here, and here for a few. Take my approach as one perspective among many.

Black Boxes

Black box models often refer to one of two ideas. The first references models that are opaque to human inspection - think random forests with thousands of trees or neural networks with millions of weights. On this usage, opaque black boxes play the foil to transparent interpretable models as opposing ends on the translucency spectrum.

While the first usage is usually taken to be a pejorative, the second refers not to the contents of the model itself but to the epistemic state of the developer/user with respect to the model. Putting the characterization in terms of the relative ignorance of the developer/user separates the context of the model’s construction from the model itself.

For instance, we can imagine being handed a model (perhaps behind an API) without any information about how it was built except knowing its inputs/outputs and labeling such a model a black box. For all the developer/user knows, the model is arbitrarily complex. A good example of the second usage is with the LIME paper which offers a method for “explaining the predictions of any classifier.”

I find it most fruitful to use opaque for the first meaning and reserve black box for the second usage.

Explainability

Explainable models are an odd and interesting class of machine learning models. They encompass interpretable models as well as most (but not all) of the middle-ground between opaque and transparent. A model is explainable if it belongs to a class of models for which a reliable explanation method exists.

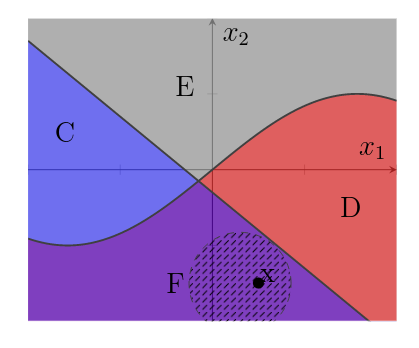

This begs the question of what even is an explanation! While some define explanations narrowly, I want to broadly define an explanation as a reason for a model’s behavior. This approach recognizes that there is a multiplicity of explanation types and methods for generating those explanations. For instance, the notion that I’m most interested in is local explanation which looks at the behavior of a model immediately around a point of interest in the feature space when explaining a model’s prediction at that point. My current work involves studying the local explanation of classifiers from a topological perspective.

While some explainability approaches try to work for all applications, e.g. LIME, others are domain-specific such as methods for NLP and computer vision.

You may notice that we were vague about what it means to be a reliable method above. This is because reliability is a fuzzy notion that comes in degrees. Broadly speaking, a method is reliable if it is able to often produce faithful explanations of model behavior within its intended domain.

Finally, let’s note that not all models are explainable. Practitioners may have the intuition that all machine learning models are explainable, but this is likely because most model architectures commonly used in practice permit explainability methods (the jury is still out for complex neural networks, especially those with discontinuous activation functions). Here are two cases that will likely not allow for reliable explanation methods. Consider a single variable classifier that labels irrational numbers “A” and rational numbers “B”. For a more extreme example, let us consider a single variable classifier that assigns an algorithmically random set of real numbers “A” and all else “B”.

Interpretability

Interpretable models are the counterpart to opaque models and are transparent on the translucency scale to continue the analogy above. Their architecture is sufficiently simple to allow the developer/user to reliably predict the model’s behavior with a reasonable amount of effort. Common interpretable models include decision trees, linear regression, and GLMs, though not all instances of these models are interpretable.

Similar to explainability, interpretability is domain-specific with different approaches used for varying tasks, so there is no single unifying notion. For instance, see here for work on interpretable computer vision models.

Unlike explainability, however, interpretablility makes direct reference to the cognitive limitations/ability of humans. Interpretable models tend to have human-readable features (so much for PCA) and a limited number of features overall, often fewer than 10 features.

Given the transparency of interpretable models, explanations are built into their architecture so-to-speak and do not require a mediating explanation method. These explanations may take the form of comparing the signs and magnitude of coefficients in a linear regression or counterfactual paths through a decision tree. Explanations generated from interpretable models are always reliable in the sense used above, excluding operator error.

The Case for Interpretability in the Wild

Recently, an argument has popped up in favor of using interpretable models rather than explanation methods when models are used in applications that inform decisions or affect users. While other arguments for interpretable models exist, I want to focus on this one in particular. Here’s what I take to be a convincing rendition of the argument:

Machine learning models are increasingly being employed to support high-stakes decisions in healthcare, the court system, and so forth. To trust a model to support these decisions in the wild, users and developers alike are interested in the reasons for a model’s prediction. Explainable models and interpretable models both offer such reasons: the former through domain-specific explanation methods, and the latter in virtue of its transparent structure. While reasons from interpretable models are justified sui generis, what justifies the reasons provided by the particular explainability method chosen? Isn’t this just passing the buck from the model to the explainability method? This generates a justification regress of sorts (not uncommon to epistemologists) that overburdens both developers and users and that can be avoided by using interpretable models when interpretable models are available. Therefore, we should deploy only interpretable models in the wild when interpretable models are available.

This argument is a strengthened version of the one given in Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead (That argument undersells explainability methods by narrowly defining explanations as global approximations and, in doing so, assumes what the author is trying to prove: explanations are at most as trustworthy than the models they’re trying to explain).

The Case Against Interpretability in the Wild

One interesting argument posits that interpretability is a means and not an end. The ends in question for machine learning models are fairness, privacy, stability, causality, and so forth. With the focus on interpretability, we may be (implicitly) assuming both that interpretability is a means at getting at these ends and, more strongly, that interpretability is the only means to get at these ends. At the very least, this should be suspect, since interpretability is domain-specific and lacks a unified definition.

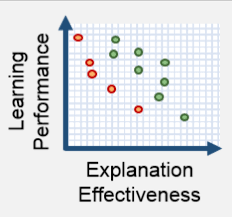

Here are some consequences of a potential undue focus on interpretability. Firstly, by constraining our model’s architecture to meet interpretability requirements, we are sacrificing some accuracy (though this amount is sometimes over-exaggerated as in the graphic to the right and sometimes under-exaggerated.) Secondly, legislating interpretability beyond a “best practice” in some contexts would conform to some interpretability notion(s) at the expense of others.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee