Economic Methodology Meets Interpretable Machine Learning - Part II - Friedman's 1953

In this series of posts, we will develop an analogy between the realistic assumptions debate in economic methodology and the current discussion over interpretability when using machine learning models in the wild. While this connection may seem fuzzy at first, the past seventy years or so of economic methodology offers many lessons for machine learning theorists and practitioners to avoid analysis paralysis and make progress on the interpretability issue - one way or the other.

This post introduces Milton Friedman’s 1953 essay The Methodology of Positive Economics which takes the position that economic theories should be evaluated only on their predictions within some specified domain. This article has been called “the most cited, the most influential, and the most controversial piece of methodological writing in 20th century economics” and plays the foil (and occasionally the bogeyman) in much of the economic methodology literature. This is so much so that it is often referred to as Friedman 1953 or even F53.

To illustrate this point, one influential commentator sums up his view on Friedman’s methodology:

“if what you are doing looks like Popper or Friedman (1953), you are doing something gravely wrong. Friedman’s positive economics essay is so influential, though, that we need continue battening down the hatches as its destructive tempest swirls.”

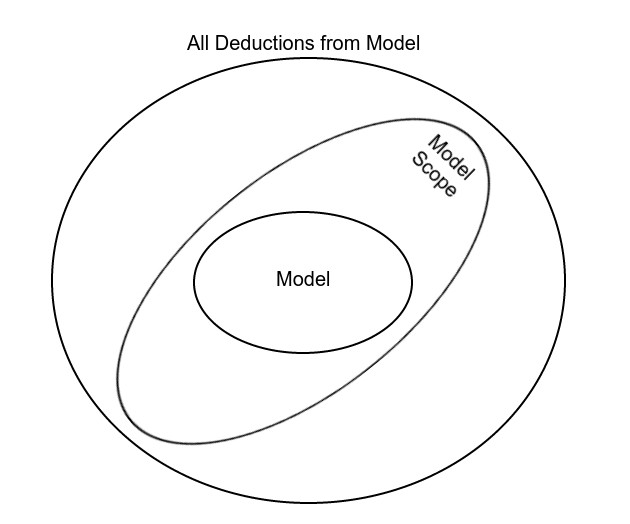

For Friedman, economic theories consist of two parts: the model and the scope of the model. A model may be thought of as a set of propositions, and the scope is the range of instances that the model can be evaluated on for predictive accuracy. In this setup, predictions are just deductive inferences from the model. The scope component is necessary to combat the position that assumptions of models ought to be as realistic as possible, since a model always deductively predicts/entails its assumptions. This leads to the as if interpretation of economics where consumers and firms behave as if they satisfy the assumptions of economic theory in some instances.

Motivating Example

Friedman offers the following example:

“Consider the problem of predicting the shots made by an expert billiard player. It seems not at all unreasonable that excellent predictions would be yielded by the hypothesis that the billiard player made his shots as if he knew the complicated mathematical formulas that would give the optimum directions of travel, could estimate accurately by eye the angles, etc., describing the location of the balls, could make lightning calculations from the formulas, and could then make the balls travel in the direction indicated by the formulas. Our confidence in this hypothesis is not based on the belief that billiard players, even expert ones, can or do go through the process described; it derives rather from the belief that, unless in some way or other they were capable of reaching essentially the same result, they would not in fact be expert billiard players.”

In this example, we are attempting to model the behavior of expert billiard players. The model itself may be some sort of optimization solving for force and direction given the placement of balls on the table, and the scope of the model is limited to the force and direction of a given shot. Friedman argues that this optimization model for expert billiard players is good insofar as it accurately predicts shots which seems trivially (and maybe circularly) true in this instance. It’s not that the expert billiard player actually solves this optimization problem with each and every shot; rather, the billiard player acts as if their behavior was determined by some solving a mathematical program. (As an aside, I wonder how much this example was influenced by the Quadrangle Club.)

Theory Choice

Friedman ventures into the philosophy of science with a wider discussion of theory choice. On Friedman’s view, predictive accuracy within the model’s/theory’s scope is the primary criterion for choice between models/theories. This signals that his view is akin to instrumentalism about scientific theories. Rather than being concerned with the truth or falsity of scientific theories, instrumentalist views hold that theories that better perform according to some metric(s), e.g. predictive accuracy, should be preferred to those that do not. While predictive accuracy takes primacy, if two models/theories are similarly accurate with respect to a defined scope, then we may appeal to other theory virtues such as simplicity and so forth.

A bit more daringly, Friedman also argues that “the more significant the theory, the more unrealistic the assumptions” (I believe he is heavily influenced by Karl Popper’s the more significant the theory the less likely it is to be true in saying this). If two theories are similarly accurate but the former has a wider scope than the latter, then the former will require a more complete description of reality, so its assumptions must be less accurate or more unrealistic. But we don’t need to worry about this dubious proposition here.

In Practice

On the one hand, Friedman’s methodology is not only difficult for the practitioner/economist to follow, but Friedman did not always follow it. On the other hand, Friedman’s economic methodology looks a lot like machine learning when viewed as an engineering task. Friedman seems to talk about economic theory the same way that data scientists and machine learning engineers talk about black-box models. Machine learning models are associative rules between variables that may or may not reflect actual relationships in the wild, and we restrict the scope of our models to distributions of data similar to the training data. (More on this analogy in future posts in this series.) In this way, Friedman seems to consider the practice of economics to be model building rather than explaining relationships between economic variables or isolating causal mechanisms (which both may just be a product of accidental historical trends).

Closing Thoughts

Kevin Bryan summarizes Friedman’s view succinctly: “He thought that when theories say assumptions A implies consequence B, and A is wrong, we need to save the inference by claiming that we only care about B.”

Friedman 1953 is the first essay in the collection Essays in Positive Economics of the same year.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee