Economic Methodology Meets Interpretable Machine Learning - Introduction

In this series of posts, we will develop an analogy between the realistic assumptions debate in economic methodology and the current discussion over interpretability when using machine learning models in the wild. While this connection may seem fuzzy at first, the past seventy years or so of economic methodology offers many lessons for machine learning theorists and practitioners to avoid analysis paralysis and make progress on the interpretability issue - one way or the other. But first, what’s going on with these two debates?

Interpretable Machine Learning

Machine learning models are increasingly prevalent in our lives from credit scores to autocomplete. Interpretable machine learning limits the types of predictive models available to the practitioner to those that allow humans to understand how the model inputs affect the model outputs. Put another way: interpretable machine learning models allow one to reliably predict the behavior of a model with a reasonable amount of effort. For instance, fixing the number of features, a linear classifier is more interpretable than a large random forest, since calculating a weighted sum is more transparent and simple than navigating hundreds of decision trees.

There have been recent arguments for using only interpretable models in the wild when available. Among other reasons, since humans build and deploy these predictive models (in most cases at least), using interpretable methods allows the practitioner to better trust the accuracy of predictions across all possible inputs. While this argument has its merits, there are many grades of translucency between the opaque black box and the crystal-clear interpretable model in the form of explainable models.

This debate asks where to draw the line of permissible translucency. Should we restrict ourselves to a small set of highly interpretable models when predictions are used for important decisions? If we take human understandability out of the equation, how reliable and simple should an explanation of a prediction be?

Realistic Assumptions for Economic Models

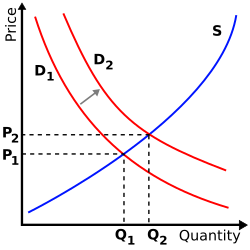

Economic models are built to capture some social interaction from the dynamics of a marketplace to strategic behavior between two parties. In instances where there are competing models for the same phenomena, it’s not immediately clear which of the models we should prefer and which to reject. One historically important position advanced by Milton Friedman in the 1950s holds that the veracity of an economic model is not relevant to its evaluation; only the predictive success of a model within a specified scope is relevant, a variant of a position called instrumentalism in the philosophy of science. We can imagine the other extreme would be to insist that good models should be descriptively accurate, a position called realism.

There are few economic methodologists today who hold these sorts of instrumentalism and realism. On the one hand, many have the intuition that economic models should capture the causal mechanism at work in the wild. Perhaps, this means being descriptively accurate for crucial assumptions of the economic model. On the other hand, simplifying assumptions are often included in models for a variety of reasons such as analytical tractability, so we don’t expect economic models to be always fully accurate. This debate asks where to draw the line between instrumentalism and realism, how to choose between a predictively accurate but unrealistic model and a descriptively realistic but inaccurate model, and so forth.

Plan for Future Posts

If you want keep up to date with this series, you can subscribe by email in the box at the top of this page. Here is a brief summary of each entry:

Part I gives an overview of black box, explainable, and interpretable machine learning models. We sketch a few arguments focusing on model trust against using black box models in the wild. While some argue for using explainability techniques such as LIME, others push for restricting practitioners to only deploying interpretable models when available and appropriate.

Part II introduces Milton Friedman’s 1953 article The Methodology of Positive Economics. This article is regarded as “the most cited, influential, and controversial piece of methodological writing in twentieth-century economics”, arguing that the assumptions of an economic model are unimportant so long as the model is predictive within its domain.

Part III looks at responses to Friedman by Paul Samuelson, Stanley Wong, and Dan Hausman which capture the some of the intuition of what’s problematic with Friedman’s argument.

Part IV considers the current state of the realistic assumptions debate and introduces two contemporary arguments: one in support of instrumentalism and another which holds that economists follow a middle position in practice.

Part V ties together the analogy that’s been building during the first four entries. We’ll argue for two conclusions for interpretable machine learning: one practical and the other theoretical.

Part VI considers some objections and pain points where the analogy breaks down. For instance, we will look at how differences in the aims of economics and machine learning affect our conclusions.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee