Economic Methodology Meets Interpretable Machine Learning - Part III - Responses to Friedman's 1953 on the Realism of Assumptions

In this series of posts, we will develop an analogy between the realistic assumptions debate in economic methodology and the current discussion over interpretability when using machine learning models in the wild. While this connection may seem fuzzy at first, the past seventy years or so of economic methodology offers many lessons for machine learning theorists and practitioners to avoid analysis paralysis and make progress on the interpretability issue - one way or the other.

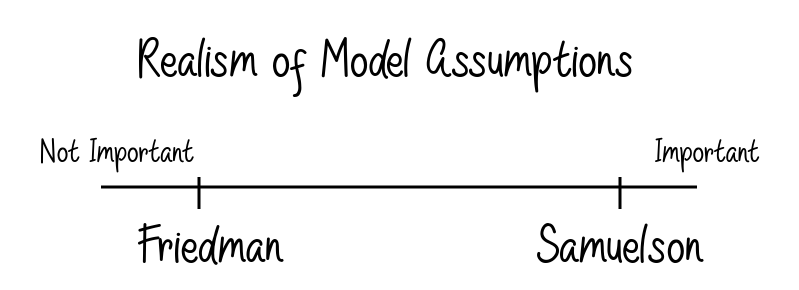

This post discusses three responses to Friedman 1953 (which we introduced in Part II). Friedman’s contention, termed the “F-Twist” by Samuelson, is that economic theories should be evaluated only on their predictions within some specified domain. The F-Twist puts Friedman on the instrumentalism end of the realism of assumptions debate. The responses by Paul Samuelson, Stanley Wong, and Dan Hausman discussed below provide various lenses though which to view the problem of the realism of assumptions and, ultimately, in my view, renders the F-Twist untenable in isolation.

Samuelson’s Logic

Much like Milton Friedman, Paul Samuelson is one of the preeminent economists of the post-war period (though he is perhaps not as well known today). Samuelson and Friedman differed in their methodology just as they differed politically (Samuelson with a Keynesian bent and Friedman toward libertarianism). Samuelson’s critique of the F-Twist is spelled out in a discussion paper from the 1963 American Economic Association meeting where he argues for a sort of realism about assumptions.

Samuelson takes a deductivist position in his critique and, essentially, charges the F-Twist with affirming the consequent. Let’s walk through Samuelson’s setup. He takes a model B to be a set of propositions in some formal language. Friedman’s analysis suggests that there exists a set C that are the consequences of B and a set A that is the assumptions of B. The assumptions A of the model B are logically equivalent to B but may be more succinctly expressed. Similarly, the consequences C of the model B is logically equivalent to B but is likely larger, since C contains B. On this view, A = B = C (at least up to deductive closure). Here is where Samuelson offers his interpretation of the F-Twist:

A theory is vindicable if (some of) its consequences are empirically valid to a useful degree of approximation; the (empirical) unrealism of the theory “itself,” or of its “assumptions,” is quite irrelevant to its validity and worth.

As Friedman points out, we’re often interested in predictions within a limited scope which we can call C-, a subset of C. Notice that C- is logically equivalent to some fragment of the model B, which we will call B-, and a fragment of the assumptions A, which we will call A-. Samuelson’s critique is that, on the one hand, the empirical adequacy of C- has no bearing on the empirical adequacy or reasonableness of A. On the other hand, the falsity of a proposition in A- implies that the propositions in C- are not necessarily true.

So realism of assumptions does matter! Samuelson’s view acts as a realist counterpart to the F-Twist. It looks like this is a reasonable summary:

One thing to note here is that Friedman and Samuelson may have been talking past each other a bit. While Friedman’s setup seems to mesh better with econometric models and statistical analyses, it’s not clear how Samuelson’s deductive methodology works in practice in a stochastic world. Samuelson’s approach seems much more focused on formal reasoning.

Wong’s Explanations

Stanley Wong’s 1973 AER paper The “F-Twist” and the Methodology of Paul Samuelson argues that Friedman vs Samuelson in methodology is a false dichotomy. There’s more on the menu than instrumentalism and descriptivism (what Wong calls Samuelson’s methodology). Moreover, Wong argues that both theories are inadequate because they lack an essential component of models: explanatory content.

Here is how Wong closes his article:

the descriptivist goal of logical equivalency denies a theory any explanatory content while the instrumentalist’s particular obsession with predictions disregards the explanatory content of a theory. The choice, then, is not between instrumentalism and descriptivism but between them both and the view that a theory is explanatory and informative, one which provides an answer, albeit a tentative one, to the question,”Why?”

There are two ways to read this quote on how the above graph is wrong. The first is that methodology is multidimensional and requires a second axis for explanatory content. While interesting, it’s not clear that we have to introduce this complexity. The second reading is that we should care about the realism of assumptions of a model inasmuch as they increase or enable the explanatory or informative content of the model.

Hausman’s Extensions

In Why Look Under the Hood?, Dan Hausman offers a simple and compelling argument for why we ought to care about the realism of assumptions to some extent. He offers us a reconstruction of the argument for the F-Twist:

- A good hypothesis provides valid and meaningful predictions concerning the class of phenomena it is intended to explain. (premise)

- The only test of whether an hypothesis is a good hypothesis is whether it provides valid and meaningful predictions concerning the class of phenomena it is intended to explain. (invalidly from 1)

- Any other facts about an hypothesis, including whether its assumptions are realistic, are irrelevant to its scientific assessment. (trivially from 2)

Now, consider an argument of same form but regarding evaluating used cars rather than economic models:

- A good used car drives safely, economically and comfortably. (oversimplified premise)

- The only test of whether a used car is a good used car is to check whether it drives safely, economically and comfortably. (invalidly from 1)

- Anything one discovers by opening the hood and checking the separate components of a used car is irrelevant to its assessment. (trivially from 2)

Just as there is something to be gained by looking under the hood of a used car, there is utility in inspecting the assumptions of models!

Similar to how Wong argued that explanatory content is an essential part of a scientific or economic model, Hausman argues that models/theories are used to guide us in new circumstances and should be judged accordingly:

Similarly, given Friedman’s view of the goal of science, there would be no point to examining the assumptions of a theory if it were possible to do a “total” assessment of its performance with respect to the phenomena it was designed to explain. But one cannot make such an assessment. Indeed the point of a theory is to guide us in circumstances where we do not already know whether the predictions are correct. There is thus much that may be learned by examining the components (assumptions) of a theory and its “irrelevant” predictions. Such consideration of the “realism” of assumptions is particularly important when extending the theory to new circumstances or when revising it in the face of predictive failure.

Hausman’s take should be intuitive to machine learning practitioners, for instance, when considering the behavior of a model a weird points in the feature space. Perhaps, for some application, we choose a tree-based model over a polynomial regression if the distribution of our data is wide and the regression is asymptotic in some directions.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee