Interesting Articles I've Read in 2025

∷

Books: 2025 - 2024 - 2023 - 2022 - 2021 - 2020 - 2019 - 2018

Below are some interesting articles I’ve read in 2025. They fall into a few categories: the mathematics of data privacy, popular mathematics, politics, and nineteenth century philosophy. For data privacy, we look at how technical details may be hindering adoption of differential privacy as well as scaling laws for differentially private language models. Next, we look at excellent popular math articles introducing the Collatz conjecture and the Busy Beaver numbers. In politics, we explore paranoid eighteenth century political rhetoric as well as John Maynard Keynes’ reflections on the Liberal party after a disastrous election in 1924. Finally, we look at two philosophical movements in mid-nineteenth century America and an 1875 article on the relation between the verifiability and discoverability of truths.

If you have some thoughts on my list or would like to share yours, send me an email at brettcmullins(at)gmail.com. Enjoy the list!

Setting $\epsilon$ is not the Issue in Differential Privacy

Author: Edwige Cyffers

Publication: NeurIPS Proceedings

Published: 2025

Link: arXiv

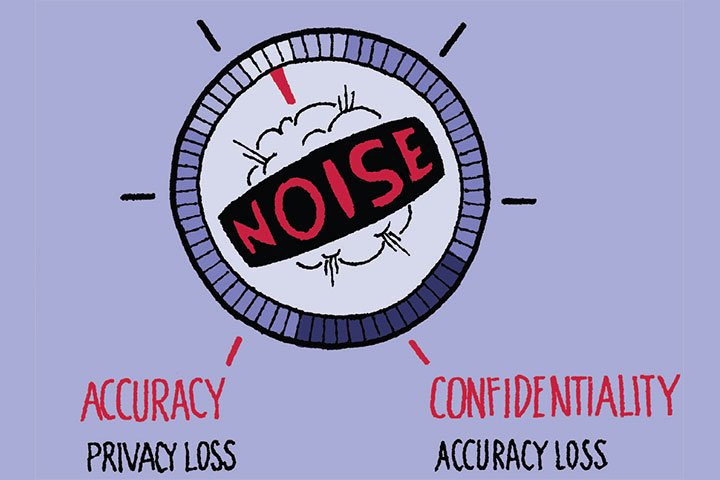

When one hears about a deployment of differential privacy, the usual followup question is “under which privacy budget?” The privacy budget $\epsilon$ refers to the parameter in differential privacy that quantifies how much information from one’s dataset is leaked in the worst case. A smaller $\epsilon$ means stronger privacy guarantees, while a larger $\epsilon$ allows for more accurate results but weaker privacy protection. The early literature on differential privacy often suggested values for $\epsilon$ between 0.01 and 1. However, in practice, many deployments of differential privacy have used much larger values, sometimes exceeding 10 or even 100. In empirical DP research, we often seek to design mechanisms that work well for both large and small privacy budgets and often evaluate them on a grid of values between $\epsilon = 0.01$ and $\epsilon = 100$.

The choice of $\epsilon$ is often viewed as a critical decision in deploying differential privacy; however, reasoning about the privacy loss is difficult, especially for non-technical policymakers and business partners. Cyffers argues that focusing too heavily on the choice of $\epsilon$ can unfairly hinder the adoption of differential privacy. Instead, she contends that this difficulty is inherent to any rigorous privacy risk assessment and that DP simply makes these trade-offs explicit. Moreover, this focus may lead decisionmakers to adopt less rigorous privacy-preserving techniques that are easier to understand but offer weaker (or no) privacy protection other than security by obscurity.

The Dangerous Problem: the century-long struggle to prove the Collatz conjecture

Author: Joe Kloc

Publication: Harper’s Magazine

Published: 2025

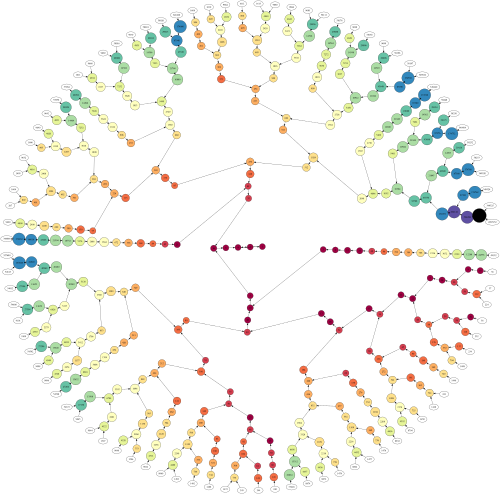

Consider a sequence of natural numbers generated by the following rules: starting with a natural number, if the number is even, divide by two; if the number is odd then multiply by three and add one. Rinse and repeat. An interesting property is that all known cases eventually yield a repeating cycle of $4, 2, 1$. The Collatz conjecture, introduced by Lothar Collatz in 1937, is that this property holds for all natural numbers.

playground for visualization

We may find it comforting that the conjecture holds for the first several quintillion numbers (checked using solvers). However, it is possible that the first counterexample is quite large. For example, the Pólya conjecture held up through an exceedingly large number of cases. This problem has an allure to it emanating from its simplicity of presentation but evasion of any solution. Kloc concludes by intimating that this and other such unresolved number theoretic problems are possibly independent of ZFC (the standard axioms of set theory).

This short article is an excellent example of math communication (and in Harper’s of all places)! The writing is engaging and easy to follow yet bursting with context and excitement. In just two pages, Kloc explains the problem, its appeal and resistance to solution, and prospects for solving it. This sort of excitement and energy always reminds me of Language, Truth and Logic by A. J. Ayer, which I read in undergrad and was drawn to like a magnet.

Philosophy of the people: How prairie philosophy democratized thought in 19th-century America

Author: Joseph M. Keegin

Publication: Aeon

Published: 2024

Link: Click here

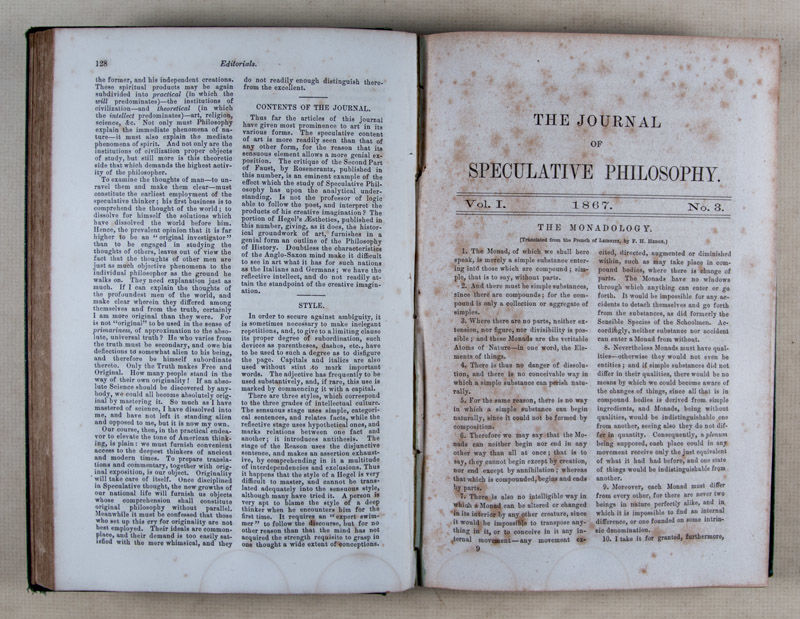

This article describes two midwest philosophic schools in the mid-nineteenth century: the St. Louis Hegelians and the Illinois Platonists.

The St. Louis Hegelians were started by the German immigrant Henry Clay Brokmeyer, who was interested in studying and disseminating the ideas in Hegel’s Science of Logic. William Torrey Harris was a St. Louis teacher who joined Brokmeyer’s circle. Harris served as the editor of their Journal of Speculative Philosophy, the first American philosophy journal, founded in 1867. Harris would later become United States Commissioner of Education and instrumental in modeling American education after the German Bildung model, e.g., by introducing Kindergarten in public education.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, Jacksonville, Illinois was a hotbed for intellectuals, including “literary clubs, feminist and antislavery groups” as well as the newly founded Illinois College. One such group was led by Hiram Kinnaird Jones and focused on the study of Plato, Greek philosophy, and the classics. Similar reading groups quickly spread to neighboring towns. By the final decade of the century, Jones’ club, now called the American Akademe, operated three journals.

Keegin offers these groups as examples when thinking about how philosophy may be practiced in the future. As Philosophy increasingly finds itself on the chopping block at universities, it’s possible that there will be far fewer professional philosophers in the near future. Keegin notes that the current university organization has only existed since the end of the Second World War, so there’s no reason to think it will continue in the current form forever.

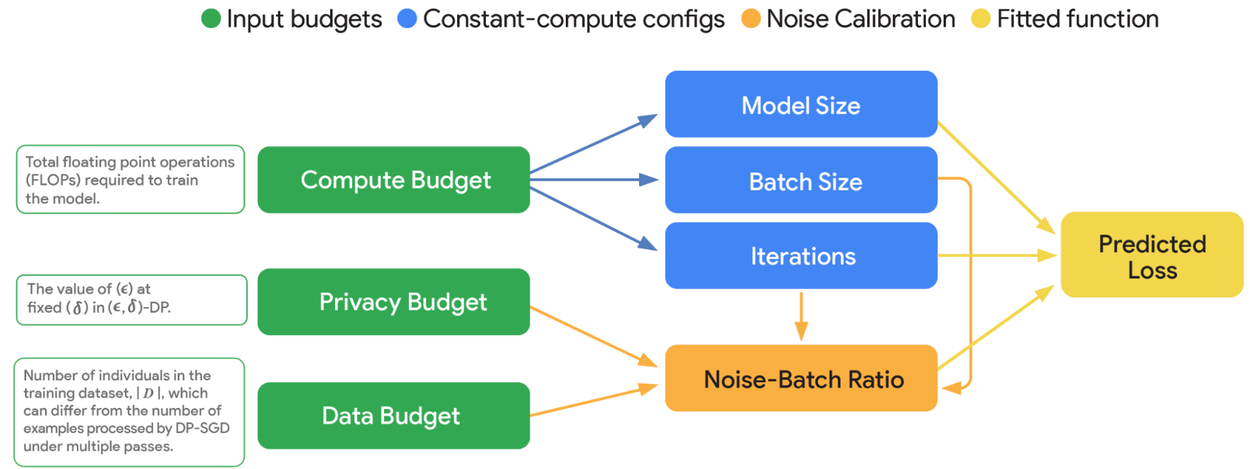

Scaling Laws for Differentially Private Language Models

Authors: Folks from Google Research and DeepMind

Published: 2025

Link: arXiv

Neural scaling laws are empirical regularities with neural network architectures that describe the relationship between model parameters and model utility. The usual citation here is Kaplan et al. (2020), which finds that model utility depends strongly with a power law relationship on each of dataset size, number of model parameters, and compute budget. These laws can guide model training by suggesting which knobs to turn and are an excellent example of a stylized fact in computer science.

This paper studies how scaling laws change once privacy is introduced to the equation. In particular, the authors compare how compute budget (a combination of batch size, number of model parameters, and number of epochs), data budget (number of observations), and privacy budget affect model utility. To this end, they fit a model to predict validation loss as a proxy for model utility by training several BERT models on a grid of parameter settings and fitting a linear interpolation model to the parameter space. Using this model, they look at what happens when we turn knobs and find that some scaling laws look quite different when privacy is added. For example, for a fixed compute budget, the optimal private model is a few orders of magnitude times smaller than the optimal non-private model. Using these scaling laws as a guide, they trained and released VaultGemma, an open language model with 1.3 billion parameters fully satisfying differential privacy.

Illuminating Conspiracy

Author: S. Jonathon O’Donnell

Publication: History Today

Published: 2020

Link: Click here

Conspiracies in American political rhetoric are not a recent phenomenon, e.g., the Illuminati scare in the late eighteenth century. The Illuminati originated as a small Enlightenment society in Bavaria in 1776 and, a decade later, was formally quashed by the conservative Catholics. Approaching the turn of the century, the Illuminati became a hidden force of lore upending society and the cause, e.g., of the age of revolutions. In the late 1790s, various conservative preachers, including Timothy Dwight, the President of Yale, used the Illuminati to rail against the recent wave of French and Irish immigrants as well as the campaign of future president Thomas Jefferson. This fervor died down in 1799, however.

As with the European witch hunts, in both the Illuminati panic and its later echoes, the real threat came from the counterconspiracy rather than from any conspiracy itself. Imagining themselves at risk of dark powers, Federalist preachers and the press organised in opposition to those powers. The immediate result was a threat not just to those it targeted but to free speech. While this threat passed, the moment left scars that have not faded as readily. As one of the earliest incidents in America’s long history of political invocations of the demonic, the Illuminati scare warns that the danger of demonology is not the demon, but the demonologist who imagines demons to be fought.

Who Can Name the Bigger Number?

Author: Scott Aaronson

Publication: Shtetl-Optimized

Published: 1999

Link: Click here

Consider a game where two players quickly write down the largest number they can. One may write a number with lots of digits or more compactly using exponentiation. Writing even more compactly, we have the Ackermann function which, given input $n$, applies an order $n$ operation $n$ times. Then $f(1) = 1$, $f(2) = 2+2 = 4$, $f(3) = 3^3 = 27$, $f(4) = 4^{4^{4^4}}$, etc. The order 4 operation is called tetration and applies exponentiation to the fourth power four times. From four onward, this function grows extremely fast. It’s the standard example of a function that’s recursive but not primitive recursive (it grows more quickly than any primitive recursive function).

Aaronson now introduces the Busy Beaver function. The $n$-th Busy Beaver number $BB(n)$ is the maximum number of steps that a Turing machine with $n$ states that halts takes before halting. Note that this is the maximum over all Turing machines with a given number of states that compute a function. Unsurprisingly, $BB$ grows very quickly. Since the Ackermann function is computable, the Busy Beaver function is strictly larger (at least asymptotically). At the time of writing, only up to the fourth Busy Beaver number was known; however, it has since been shown that $BB(5) = 47176870$.

It’s important to note that the Busy Beaver function is not computable. Suppose $BB$ was computable. Consider an arbitrary Turing machine $M$ with $n$ states. Then, for any input, we can determine if $M$ will halt by observing that it either has halted or has run for at least $BB(n)$ steps. But the Halting Problem is undecidable! Is it possible to go bigger than the Busy Beaver numbers? Not in the standard model of computation. Hypercomputation refers to problems belonging to point classes of the arithmetic hierarchy beyond $\Delta_1$. These point classes are closed downward under inclusion, so “hyper” Busy Beaver numbers for higher point classes are strictly larger than the Busy Beaver numbers for recursive sets. But, in general, these “hyper” Busy Beaver numbers require a worked out account of hypercomputation to be well-defined.

This is an excellent blog post that introduces the reader to a breadth of ideas while having a lot of heft. I aspire for my writing to approximate this!

Can Truths be Apprehended Which Could Not Have Been Discovered?

Author: W. R. Greg

Publication: The Contemporary Review

Published: 1875

Link: HathiTrust

Imagine one obtains an idea in some way like from an apple falling on one’s head. Supposing the proposition expressing this idea is true, Greg asks if we could have discovered the proposition through human faculties and empirical evidence irrespective of its content. For propositions that we can verify, he answers in the positive, since the cognitive tools used to verify the proposition are the same used to arrive at it, i.e., verifiability implies discoverability. His evidence for this is a bit shaky so far, but Greg points out that this explains the futility of attempting to verify religious, spooky, or supernatural propositions using rational or empirical methods. Since these ideas are not discoverable by humans - being outside the scope of our cognitive architecture - they are not verifiable.

I thought that Gödel sentences present a counterexample to Greg’s claim, at least within the scope of formal theories, which I wrote about as part of my look back at research from 1875. Gödel’s first incompleteness theorem states that any theory sufficiently strong enough to model arithmetic contains a true sentence that’s not provable, called a Gödel sentence for the theory. The Gödel sentence is verifiable by its construction; however, it’s not provable, i.e., discoverable, from below. A reader noted that Gödel sentences are consistent with Greg’s claim, since a Gödel sentence is only verifiable from a meta-theoretic perspective, i.e., from outside the theory.

Am I a Liberal?

Author: John Maynard Keynes

Publication: The Nation and Athenaeum

Published: 1925

Link: HET Website

The 1924 UK General Election saw a crushing defeat for the Liberal party, who lost 118 of its 158 seats in the House of Commons. This election split the electorate between Labour and Conservatives, a situation that has persisted (mostly) ever since. Foreseeing this, Keynes asks to which of the two parties he should switch his allegiance. On one side, he finds the Conservatives unpalatable whose hard-core is focused on preserving their accumulated power, status, and wealth, even at the expense of new ideas that would benefit everyone. On the other, he calls the hard-core of Labour “the Party of Catastrophe”, who only see the possibility of progress through tearing down existing institutions, even at the expense of new ideas that would benefit everyone.

Keynes sees room for a third party focused on addressing ever-changing economic issues through institutions, which are somewhat insulated from politics. This new Liberal party would need to shed the baggage of its predecessor, which remains mired in nineteenth century policy debates, to focus on economic issues currently facing the voting public, including the increasing role of women in the economy. Rather than forming a new coalition from the ashes of the Liberal party, both left and right parties in the West throughout the twentieth century adopted aspects of Keynes’ technocratic view. This article is prescient today as many Western democracies face similar issues of political polarization and disaffected voters. I read this article as part of my look back at research from 1925.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee