An Utterly Incomplete Look at Research from 1824

This series looks at research from years past. I survey a handful of books and articles in a particular year from math, economics, philosophy, international relations, and other interesting topics. This project was inspired by my retrospective on Foreign Affairs' first issue from September 1922.

The French Revolution cast a long shadow over early nineteenth century thought. Many of the selections below are concerned with the aftermath of the Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars both economically and intellectually. The pseudonymous Piercy Ravenstone critiques England’s system of public finance and its handling of the massive debt resulting from the wars. John Stuart Mill reviews a debate about the effects of war-time spending on prices. His father, James Mill, offers analyses of government, jurisprudence, freedom of the press, and international law along utilitarian lines for the Encyclopedia Britannica. William Stevenson argues that the moral convulsion among the people caused by the French Revolution opened the door for intellectual progress.

A minor strand of thought is a critique of the Enlightenment project. The philosopher Mary Shepherd argues against David Hume’s empiricist and skeptical account of causation. Alexander Blair critiques encyclopedias as obstructing progress in thought and homogenizing knowledge.

by Richard Parkes Bonington

Throughout reading for 1824, I became annoyed with the prolific writer Thomas De Quincey. On the one hand, he presents himself as the unquestioning adherent of the economist David Ricardo. On the other hand, he arrogantly muses on extensions and improvements on Ricardo’s work, in his eulogy no less. I hold out some hope for the future, however, since De Quincey’s analysis of Macbeth from last year was quite good and his autobiographical account of opium addiction is well regarded.

I most enjoyed reading John Ramsay McCulloch’s history of economic thought and William Stevenson’s analysis of periodicals and the public intellect. McCulloch’s short book tells an interesting story and provides context on how an influential classical economist viewed their enterprise. Stevenson’s article studies the interplay between periodicals and intellectual progress, which is not so far off from what I’m doing with this project.

I came across a very interesting book Sketches of the Philosophy of Apparitions by Samuel Hibbert-Ware too late in the year to actually read it in time. This book is one of the first to offer a materialist explanation of ghosts and apparitions as pathologies of the human mind. I will catch up with this and other interesting reading that I initially overlooked in a future post. If I’ve missed anything interesting from 1824 that you enjoy, shoot an email my way at brettcmullins(at)gmail.com.

Economics

Discourse on Political Economy by John Ramsay McCulloch

Thoughts on the Funding System and Its Effects by Piercy Ravenstone

The Services of Ricardo to Political Economy by Thomas De Quincey

Review of Von Jakob’s Principles of Taxation

War Expenditure by John Stuart Mill

Dialogues of Three Templars on Political Economy by Thomas De Quincey

Philosophy

An Essay upon the Relation of Cause and Effect by Mary Shepherd

On the reciprocal influence of periodical publications by William Stevenson

Review of History of Philosophy

Thoughts on some Errors of Opinion by Alexander Blair

Math

On the apparent direction of eyes in a portrait by William Hyde Wollaston

International Relations

Essays for the Encyclopedia Britannica by James Mill

Mr. Ingersoll’s Discourse

Observations on Parliamentary Reform by David Ricardo

Economics

A Discourse on the Rise, Progress, Peculiar Objects and Importance of Political Economy

Author: John Ramsay McCulloch

Link: Google Books

This short book is regarded as the first history of economic thought from a classical economist but is as much an argument for the field of political economy itself. McCulloch presents economics as approximating a completed science and spends much of the book sketching its development. He begins with the mercantilists who thought about the right things in the wrong way by, among other issues, advocating for restrictive trade policies. Dudley North is credited with turning the tide toward liberal thinking in the late seventeenth century.

from the Online Library of Liberty

François Quesnay and the Physiocrats were the first to systematize economics as a science of wealth i.e. think in terms of general laws. With The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith offered the first comprehensive treatment of economics. McCulloch argues that Smith’s work was a great leap forward but that the field was still incomplete. He credits David Ricardo with filling in most of the gaps such as with the labor theory of value. This chronology is not substantially different than other texts such as Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers from 1953.

Though often confounded with political theory, McCulloch argues that political economy is a distinct field. He defines it as the science of wealth and the laws governing its production, distribution, and consumption. Political economy is indispensable to the legislator from taxation and regulation to trade between states. Doing otherwise is essentially being willfully ignorant.

Thoughts on the Funding System and Its Effects

Author: Piercy Ravenstone

Link: Google Books

From North America to the European continent, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw Britain continually at war. In the course of funding these efforts, the government accumulated considerable debt and suspended the convertibility of bank notes into gold, generating the so-called bullionist controversy. This short book critiques England’s system of public finance along with its strategies to reduce the debt burden.

Ravenstone argues that government borrowing has the potential to be unjust since the burden of the debt falls on future taxpayers. With debt resulting from the wars, he charges that a great deal was squandered and what wasn’t did not yield sufficient returns. Troubles are compounded by the plan to pay off the debt through introducing a temporary tax tied to debt reduction. Not only is such a fund ripe for abuse, but economic growth is hindered by transferring money to the wealthy that hold bonds. Instead, he recommends reducing spending, taxing the idle classes, and promoting economic growth.

The wealth of a nation should be measured by its productive capacity rather than its accumulated capital. This follows from viewing labor as the ultimate source of value, which was commonly held by classical economists. Both labor and capital are important to economic growth, particularly relevant since this was written during the latter bit of the first industrial revolution. Financing government spending through public debt distorts the market by giving an outsized return to capital and the idle classes that own it.

This book has a bit of mystery to it since the identity of Ravenstone is not known. Though often labeled as Ricardian socialist, this book leans more anti-capitalist; however, it influenced nineteenth century socialist economists such as Karl Marx.

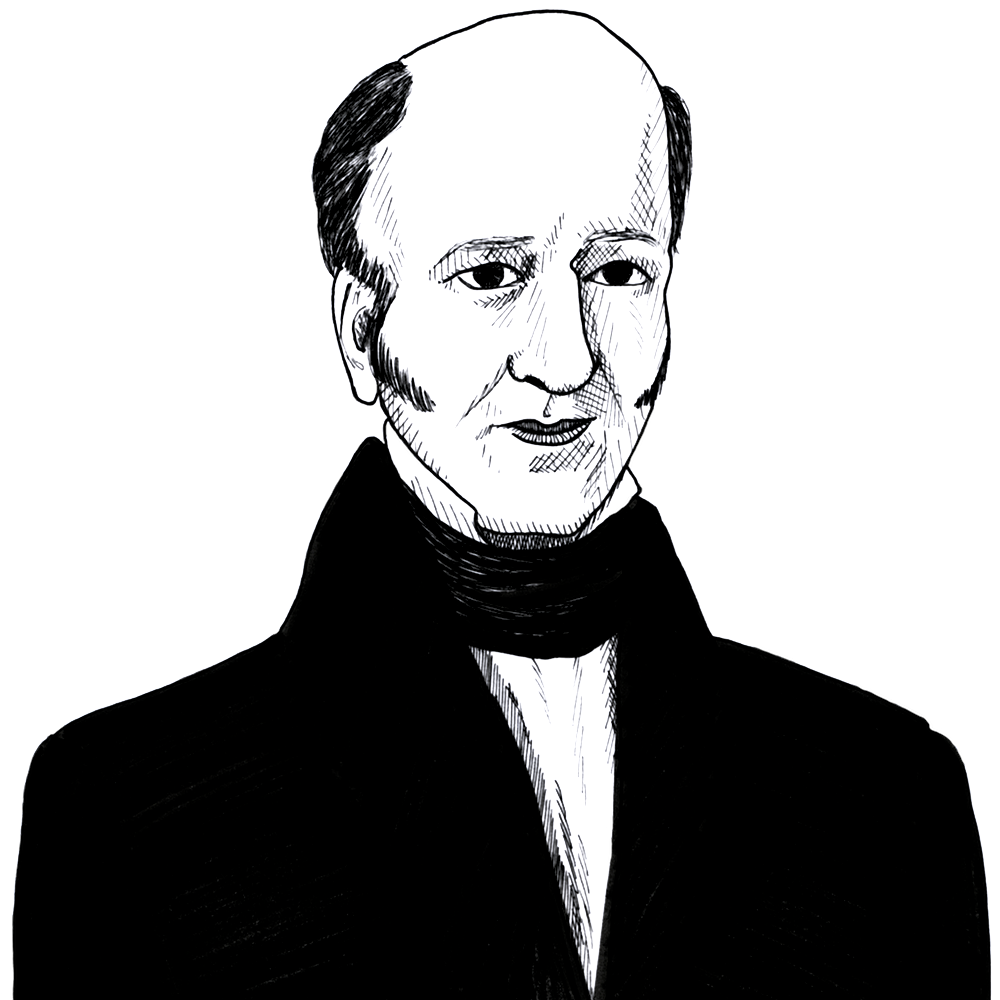

The Services of Mr. Ricardo to the Science of Political Economy, briefly and plainly stated

Author: Thomas De Quincey

Publication: The London Magazine

Link: Google Books

Leigh Guldig (2016)

In his autobiographical Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), De Quincey describes learning political economy by studying David Ricardo’s text On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), which generated criticism from some readers. De Quincey laments Ricardo’s death in 1823 along with his opportunity to learn and work with the economist. On the one hand, De Quincey pledges himself to the Ricardian school of thought; on the other hand, he arrogantly muses on extensions and improvements. This is a weird and self-indulgent article that makes the author’s excellent On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth from the prior year seem like a distant memory.

Review of Von Jakob’s Principles of Taxation

Publication: North American Review

Link: JSTOR

Prior to the development of political economy in the eighteenth century by Adam Smith and others, public finance was characterized by haphazard and unequal taxation as well as irregular and erratic expenditure. Ludwig Heinrich von Jakob’s tome Die staatsfinanzwissenschaft (1821) argues that taxes ought to be judiciously levied, spending should advance the commonwealth, and government action should be transparent and predictable.

The science of public finance balances justice, expedience, and prudence in funding the state. To this end, von Jacob holds that taxes should primarily be derived from income on both capital and labor. Moving from the domain of theory, this book surveys public finance schemes on the continent and their various follies such as the handling of paper (or inconvertible) money. This is particularly relevant given that the recent Napoleonic Wars left states saddled with debt.

War Expenditure

Author: John Stuart Mill

Publication: The Westminster Review

Link: Google Books

by Thomas Phillips

In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, the effects of government policy on the economy were increasingly put under the microscope. The pamphlet Observations on the Effects Produced by Government Expenditure during the Restriction of Cash Payments (1823) by William Blake - but not that William Blake - argues that increased spending during the war and its subsequent decrease after 1815 explains the observed pattern of high prices followed by low prices for goods. In particular, he posits that increased market stimulation led to overproduction and a general glut of goods, which then depressed prices.

In his review, John Stuart Mill sides with economist Thomas Tooke by arguing that other explanations such as seasonal variation in crop yields are sufficient to explain price trends. Mill defends an economic principle called Say’s Law that says roughly that supply creates its own demand, implying that a general glut is impossible. Moreover, Mill argues that not all spending is equal: unproductive war-time spending would not generate the same economic growth as investments in one’s industry.

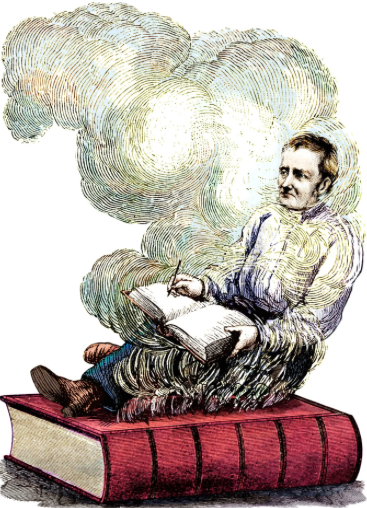

Dialogues of Three Templars on Political Economy, chiefly in relation to the Principles of Mr. Ricardo

Author: Thomas De Quincey

Publication: The London Magazine

Link: Google Books Part I Part II Part III

When we think about the value of a good today, we think about its market or exchange value. In the nineteenth century, economists also debated a notion of natural value, which can roughly be thought of as the long-run market value or value as the cost of production. In the Dialogues, De Quincey defends the position that the natural value of a good is the quantity of labor required to produce it or, in his words, “the ground of the value of all things lies in the quantity of labor which produces them”. This is the “one principle in Political Economy, from which all the rest can be deduced”, which he attributes to David Ricardo’s On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817).

De Quincey’s goal is to refine the presentation of Ricardo’s principles, which he finds to be too abstract and nuanced for the lay reader, and fend off criticism such as from Thomas Malthus. He makes the first clear with the following passage:

For the fact is - that laborers of the Mine (as I am accustomed to call them), or those who dig up the metal of truth, are seldom fitted to be also laborers of the Mint, i.e. to work up the metal for current use.

The dialogues feature three characters: a disciple of Ricardo (himself), a disciple of Malthus, and, loosely speaking, a disciple of Adam Smith. The first interlocutor spends much of the time demolishing the arguments of the others, particularly on the distinction between value being a function of quantity of labor in contrast to the cost of the quantity of labor. This is a better effort from De Quincey but struggles to get out from under his ego.

Philosophy

An Essay upon the Relation of Cause and Effect

Author: Mary Shepherd

Link: Google Books

The eighteenth century philosopher David Hume advanced a skeptical account of causation. Hume was part of the British Empiricists who viewed sense experience - as opposed to reason - as the foundation of knowledge and metaphysics. On Hume’s view, we never observe causation outright; rather, we observe the constant conjunction of events and infer causation as a matter of convention. This leads to the problem of induction, among other issues.

In this book, Mary Shepard argues that Humean causation is hollow and misses the part of causation that makes it central to knowledge. Shepard’s account sees causation as a necessary relation between properties of objects or events. We infer causation by reasoning about the properties of objects. Importantly, some properties that figure into the causal relation will be hidden from the observer (think hidden states in a probabilistic model), thus illustrating the poverty of a strong empiricist view. Along similar lines, Shepard critiques the views on cause and effect from the Humean philosopher Thomas Brown and the English surgeon William Lawrence.

by Richard Bankes Harraden

Without a more comprehensive notion of causation, Shepard holds that there is no foundation of “scientific research, of practical knowledge, and of belief in a creating and presiding Deity”. Despite being influential among an elite circle at Cambridge, Shepard’s work was largely forgotten until recently. This book received a reprint from Oxford University Press in late 2024.

On the reciprocal influence of the periodical publications, and the intellectual progress of this country

Author: William Stevenson

Publication: Blackwood’s Magazine

Link: Google Books

One way to measure how the intellect of a country changes over time is to look at what’s published in its periodicals. By intellect, Stevenson is not as much talking about scientific advancements as the overall quality of discourse. Looking back at the literature from the 1770s, Stevenson observed a dramatic rise in the quality of articles published in London periodicals over the fifty year period. Is published writing merely a reflection of changing intellect, or does causation go both ways?

by Johan Christian Dahl

Stevenson finds the literature from fifty years prior to be a bit pedestrian with respect to both topics and quality relative to the writing of his day. One driver of this is the notion of a moral convulsion. This is an event that causes radical social upheaval and a reevaluation of one’s moral landscape, which Stevenson compares to a volcano erupting and leaving fertile soil in its wake. During the time period in question, a moral convulsion was brought on by the French Revolution and the resulting turmoil.

How might periodicals influence the public intellect? Unlike books, periodicals often expose the reader to a variety of topics and the occasional gem of an article that might not have been sought out otherwise. In this way, ideas can diffuse through society. There are other avenues as well. As the number of published articles grew, outlets specialized to differentiate their collections and capture a specific audience. The resulting exclusivity increased both the prestige and utility of publishing one’s writing in this format, leading brighter minds to contribute to periodicals.

On this latter point, I couldn’t help but think that today we’ve seen some harmful effects emerge from this process of specialization insofar as the public intellect becomes fractured into echo chambers, cognitive islands, and epistemic bubbles. Regardless, this article lays out a strong case for why one should read periodicals, both then and now, and especially broader interest magazines such as The Atlantic and Harper’s.

Review of History of Philosophy

Publication: North American Review

Link: JSTOR

Histoire comparée des systèmes de philosophie, considérés relativement aux principes des connaissances humaines (1804) by Joseph Marie de Gérando is an in-depth history of philosophy from the Presocratics to the end of the modern period. This review discusses the first of three volumes upon the release of the second edition, which covers up to the early Renaissance. The reviewer laments that no such survey is available in English and provides translations of several lengthy passages.

Gérando claims to structure his history around the so-called terrible question of how we can know anyone or anything exists. Our reviewer delights in pointing out the numerous deviations from this plan. Overall, Gérando’s chronology is fairly standard and reminded me quite a bit of Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy (1946). The greatest divergence from Russell’s account, however, is Gérando’s partiality for Plato over Aristotle:

The manner of Plato is warm and enthusiastic. He thinks with all his soul, and inspires us with emotion even in his coolest moments. The other is always didactic. There is no heat in the light which he throws on the subject. The severest reason presides in all his lessons; he addresses himself to the understanding, and puts us on our guard against any kind of excitement. Plato, in short, is the high priest of philosophy, and the father of his pupils, while Aristotle has the character of a judge and a schoolmaster.

Yet, both advocate a sort of perennialism that attributes the ideas of Plato and Pythagoras to the Egyptians and the Ancient Near East.

Thoughts on some Errors of Opinion in respect to the Advancement and Diffusion of Knowledge

Author: Alexander Blair

Publication: Blackwood’s Magazine

Link: Google Books

Constructing an encyclopedia by gathering and organizing all knowledge is a strong expression of Enlightenment ideals. By the 1820s, several encyclopedias were available such as Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie (1751-1772), several editions of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and the recently published Encyclopaedia Metropolitana (1817-1845). Blair critiques these and other comprehensive projects, arguing that they promote a superficial understanding and homogenizing of information rather than deep knowledge.

by Hugh Carter

Blair argues that knowledge is highly personal and can only be advanced through willful acts of researchers that gain mastery in a particular field. He sees knowledge as more resembling know-how rather than know-that. Examples of the former include knowing how to ride a bike or bake a cake, while the latter can be expressed as propositions. Reducing one’s knowledge from the former to the latter sort diminishes it and steamrolls progress. On Blair’s account, increasing intellectual specialization is the key toward progress in the arts and sciences.

Math

On the apparent direction of eyes in a portrait

Author: William Hyde Wollaston

Publication: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London

Link: Royal Society

Have you ever been strolling around a dimly lit library at night in an old country manor and felt the eyes from a portrait of a long-dead prior owner following your every move? This short paper seeks to explain this phenomenon as an optical illusion created by the artist. We may think that we can determine the direction a portrait is looking by the shape of the irises of its eyes. The reasoning goes that the closer their gaze is to us the more circular the iris, the farther the more elliptical. This approach fails since humans are quite bad at approximating iris shape!

World War I recruitment poster

Rather, as Wollaston shows through several examples, the relative position of the iris and other facial cues determine the direction. He demonstrates this by providing several illustrations of the same eyes but with different cues, producing variation in direction. Even if this is so, why do the eyes seem to follow us? So long as we are within a cone of the portrait’s vision, we will interpret it as looking at us. The cone is largest if the face is gazing orthogonal to the painting’s plane and diminishes as the angle of the face approaches a side profile. Of course, there’s also another possibility.

International Relations

Essays for the Supplement to the Encyclopedia Britannica

Author: James Mill

Link: Internet Archive

from the Online Library of Liberty

In early nineteenth century Britain, the philosophical radicals were a group of thinkers who sought liberal reforms for the political system. Following the work of Jeremy Bentham, they held that government should be based on utilitarian principles, i.e. the best course of action is the one that maximizes the greatest good for the greatest number, and deplored the influence exerted by the aristocracy. Mill was a prominent member of this group and advocated for radical and liberal views in several essays for the Supplement to the fourth, fifth, and sixth editions of the Encyclopedia Britannica. These articles were released piecemeal from 1815 to 1824, and the four entries discussed below were collected into a single volume in 1824.

Essay on Government

How does one structure a government based on utilitarian principles? Both monarchy and aristocracy incentivize a small group to act in favor of their interests and against the majority of people. Though there’s clearly some zero-sum reasoning here, Mill quickly dispatches with these options. Direct democracy, however, is seen as infeasible and too chaotic.

Mill eventually lands on representative democracy with checks on power in the form of term limits. Without such checks, the chosen representatives are yet another form of aristocracy, since their interests are not necessarily aligned with the people. Next, Mill argues that we can restrict enfranchisement to specific subgroups but still represent the interest of the people. Notably, women are excluded! The system Mill describes looks suspiciously like the House of Commons.

Essay on Jurisprudence

The purpose of law is to define individual rights, set out punishment or sanctions for undesirable behavior, and outline rules for the administration of justice. The most important aspect of law is that it should be clearly articulated to inform decision making. That this is held to be of central importance implies that utilitarianism is meant as a descriptive account of decision making as much as a normative account of moral philosophy.

Essay on the Liberty of the Press

Similar to David Ricardo’s view discussed below, Mill holds that a free press is an important safeguard against abuses of government. Without the press, people would not know if an MP was representing their interests, possibly breaking an important feedback loop. Moreover, it’s not possible for a government body to abridge speech without doing so arbitrarily and causing harm.

The notable exceptions to a free press are in cases of libel against individuals. Just like other laws, it’s important to clearly set out what’s meant here and what sanctions one could face. I find it odd though that Mill downplays the danger of the press inciting violence.

Essay on the Law of Nations

While I find Mill to be thinking about the right things mostly in the right way, he paints a rather rosy picture of international cooperation that certainly was not warranted at the time.

Mill begins by applying the approach above by treating nations as people and defining the scope of rights, sanctions, and administration. Compared to the prior cases, his reasoning relies more explicitly on the impartial observer model to resolve disputed rights claims. He considers a case of a river that flows through many states but all want to use the waters to ship goods. The proposed utilitarian solution is that all relevant states should be granted navigation access. On its face, this sketch of a solution is reasonable but hides much of the complexity of what such access entails.

The analogy between nations and people is strained by sanctions, since there is no clear authority analogous to the state. Mill suggests the establishment of a tribunal to adjudicate disputes. While states need not cede their sovereignty to the tribunal, disregarding an unfavorable ruling would cause reputational damage and make it less likely that other states would work with and trust the offending state. This latter point was rushed and neglected to consider situations other than one state pitted against all others such as disagreement among coalitions.

Mr. Ingersoll’s Discourse

Publication: The North American Review

Link: JSTOR

Charles J. Ingersoll gave the annual address to the American Philosophical Society in 1823 on how American ideals are reflected in its social institutions through an extended comparison with European society. This review discusses several points illustrating the breadth of Ingersoll’s address but often circles back to education.

The ideals of representative democracy require an educated citizenry. As such, the United States developed an extensively funded system of public education at all levels by the standards of the time. In much of Europe, however, public education was looked on with suspicion by the ruling class and monarchs in particular. Ingersoll sees a future where American literature and science will displace that of Europe who held a commanding lead. The reviewer, however, thinks that space should be reserved in education for learning Latin and Greek. Not only do ancient languages sharpen the mind, but it allows us to pay reverence to the great writers of the past. This provides an amusing contrast to a writer one generation later who argues that the then-current methods of instruction in the ancient languages dull the mind at the “grindstone”.

At the time, books in the United States were subject to import duties, which Ingersoll sees as a hindrance to the spread and advancement of knowledge. Books were much cheaper to print domestically and copyright law was a bit of a mess i.e. unenforceable, so the duty increases the cost of speciality or antique books without favoring the domestic printing industry. The reviewer closes with a quite justified criticism of Ingersoll’s exuberance for America. In his many comparisons with Europe, Ingersoll finds himself exaggerating the gap between the two into a gulf at the expense of his credibility.

Observations on Parliamentary Reform

Author: David Ricardo

Publication: The Scotsman

Link: Internet Archive

It was commonly held in early nineteenth century Britain that freedom of the press was necessary and sufficient for the good governance of Parliament, though this idea had been quite contentious in the mid-seventeenth century. A free press provides a check on the authority of government:

The press, amongst an enlightened and well-informed people, is a powerful instrument to prevent misrule, because it can quickly organize a formidable opposition to any encroachment on the people’s rights, and, in the present state of information, perhaps there would not be found a minister who would be sufficiently daring to attempt to deprive us of it.

Ricardo holds, however, that, while a free press can be a powerful check on government action, it is a measure that works better in some cases than others, particularly large issues such as ill-motivated wars, sweeping changes to popular policies, etc. A free press can struggle to check incremental policies that are cumulatively detrimental to the public or policies that are sufficiently obscure. Ricardo argues that the only sufficient condition for good governance is mass enfranchisement, to ensure that those elected to the House of Commons represent and are accountable to the people at large.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee