An Utterly Incomplete Look at Research from 1825

This series looks at research from years past. I survey a handful of books and articles in a particular year from math, economics, philosophy, international relations, and other interesting topics. This project was inspired by my retrospective on Foreign Affairs' first issue from September 1922.

A persistent theme throughout the 1820s is the tension between Enlightenment ideals and conservative reaction. The books and articles discussed below capture various facets of this conflict. William Hazlitt’s collection of essays examines intellectuals from the turn of the century, many of whom became swept up in the Romantic movement and adopted illiberal views. J. C. L. de Sismondi’s survey characterizes international relations in the first quarter of the nineteenth century as a struggle between the forces of liberty and tyranny and is optimistic for the former. Liberal ideas were advancing steadily in education, as seen in Henry Brougham’s pamphlet on Mechanics’ Institutes and adult education and the plans to found additional universities in England outside of Oxford and Cambridge.

by Joseph Turner

Of the bunch below, I most enjoyed Samuel Bailey’s On the Nature, Measures, and Causes of Value and The Philosopher in the Kitchen by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin. The former proffers a subjective theory of value that is far ahead of its time both in content and style, and the latter is a time-capsule of French culture through a treatise on gastronomy.

There are several books I didn’t get to but are otherwise interesting and important. Appeal of One Half of the Human Race by William Thompson critiques the position of women in society and takes issue with fellow liberal James Mill’s claim in his Essay on Government that women need not be extended political rights. I discuss the preface below. Thomas Hodgskin’s pamphlet Labour Defended Against the Claims of Capital argues that labor is the source of all value and is, thereby, undercompensated. John Ramsay McCulloch’s Principles of Political Economy became the standard textbook in political economy until John Stuart Mill’s Principles from 1848. If I’ve missed anything interesting from 1825 that you enjoy, shoot an email my way at brettcmullins(at)gmail.com.

Economics

On the Nature, Measures, and Causes of Value by Samuel Bailey

Ravenstone’s Funding System

M’Culloch’s Discourse on Political Economy

Practical Observations upon the Education of the People by Henry Brougham

Philosophy

The Philosopher in the Kitchen by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

The Spirit of the Age by William Hazlitt

Philosophical Considerations on the Sciences and Savants by Auguste Comte

Mathematics

On the method of the least squares by James Ivory

Function Expressive of the Law of Human Mortality by Benjamin Gompertz

International Relations

Progress of Nations during the Last Twenty-Five Years by J. C. L. de Sismondi

Letter to Mrs. Wheeler by William Thompson

Miscellaneous

New University in London

Economics

A Critical Dissertation on the Nature, Measures, and Causes of Value

Author: Samuel Bailey

Link: Internet Archive

A common notion one finds in early nineteenth century economics is that commodities have an intrinsic value, determined by the amount of labor required to produce the good, in addition to market value. This book is an extended critique of the labor theories of value developed by David Ricardo and Thomas Malthus and expounded on by Thomas de Quincey.

Rather than an abstract property, Bailey argues that value is a relation between two commodities at a given time defined by their ratio of exchange. The relative value I assign to two goods depends on psychological considerations and may be different than the value that you assign. Moreover, the relative value may vary over time. This view requires comparatively little metaphysical baggage.

(probably)

Perhaps, instead, the amount of labor required is a good measure of value. Bailey contends that it’s unclear what’s even meant by a measure of value. A charitable view is that some common commodity such as money is a good measure of value, since we can use it as a medium to compare how much one is willing to exchange for a given commodity. This, however, falls short of the objective measure that classical economists desired, since money too can rise in value with respect to other commodities.

Another possibility is that the amount of labor required to produce a commodity is the cause of the value of the commodity. Surely, it’s a cause; however, there’s no reason to think its the cause. Even abstracting away from market conditions, the amount of capital employed in the production of a good ought to be considered as a factor. Importantly, it’s likely not the case that capital is just accumulated labor.

This book is very readable and provides a convincing critique of Ricardo’s labor theory of value. Bailey mentions Robert Torrens’ An Essay on the Production of Wealth (1821) as another recent contribution to political economy that avoids the labor theory pitfalls. In addition, Bailey’s work provides the most complete and modern citations of the time, which eases the burden of navigating the literature.

Ravenstone’s Funding System

Publication: The Quarterly Review

Link: Google Books

This is an unsigned review of the pseudonymous Piercy Ravenstone’s Thoughts on the Funding System and Its Effects (1824). This book critiques England’s method of funding its wars in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries through bond issuance, which Ravenstone alleges is both wasteful and to the benefit of the wealthy at the expense of the masses. The reviewer contends that issuing bonds by the state is more reasonable and cost effective than alternatives.

Assuming the state needs to raise money for a worthy cause such as defending its territory from an invading state, how might this be achieved? If the state doesn’t borrow directly through bonds or similar instruments, it can levy a tax on the public. While this seems like a more reasonable approach, since estates can be taxed proportional to their wealth, several wrinkles emerge. What do we do about estates that are wealthy but illiquid? Have them borrow against their assets? There are efficiencies of scale to be gained by negotiating this as a single borrower as the state would. Funding a war effort diverts capital from other investments; however, removing capital uniformly will have a worse effect on returns than only employing idle capital or capital that was less productively employed.

The reviewer throws around a lot of numbers, and it isn’t always clear where their calculations come from.

M’Culloch’s Discourse on Political Economy

Publication: The Westminster Review

Link: Google Books

This is a short and favorable review of John Ramsay McCulloch’s A Discourse on the Rise, Progress, Peculiar Objects and Importance of Political Economy (1824), which borders on advertisement. The reviewers regard this book as an important part of the coming-of-age of political economy, where the field became known and respected outside of a handful of thinkers. The reviewers pinpoint the year of ascendency to 1818, which is nearly fifty years after the publication of The Wealth of Nations (1776) and sandwiched between David Ricardo’s On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817) and Ricardo joining the House of Commons in 1819.

This is an unsigned review attributed to William Ellis and John Stuart Mill by Gonçalo L. Fonseca, the author and maintainer of the HETWebsite.

Practical Observations upon the Education of the People, Addressed to the Working Classes and their Employers

Author: Henry Brougham

Link: Internet Archive

Mechanics’ Institutes were established in the early nineteenth century to provide education and training for the working-class, particularly those in the manufacturing. The idea was to communicate the fundamentals of the natural sciences that underlie the processes in which the workers operate. These institutes more generally sought to rectify a glaring deficiency in adult education in Britain.

Henry Brougham was a Whig MP and a vocal advocate for popular education and other liberal causes such as expanding the voting franchise and slavery abolition. In this essay, he argues that providing time and a venue for workers to learn new skills and ideas would benefit the workers, the factories, and the community. On Brougham’s vision, these institutes would be joint ventures, where wealthy benefactors provide the funds for starting up, the factories guarantee the workers have sufficient time and place to meet, and the workers themselves participate and, eventually, govern the institute.

While there was some variation, the general blueprint is for an institute to house a library, hold reading groups, and offer full course lectures. Importantly, though, the institutes sought to fend off partisan dispute by discouraging or even banning books and lectures on theological or political matters. By the time of writing, several Institutes had been founded from London to the industrial north and Scotland. Many of these institutions exist today through lineal descent and form a large part of the higher education in the UK.

Philosophy

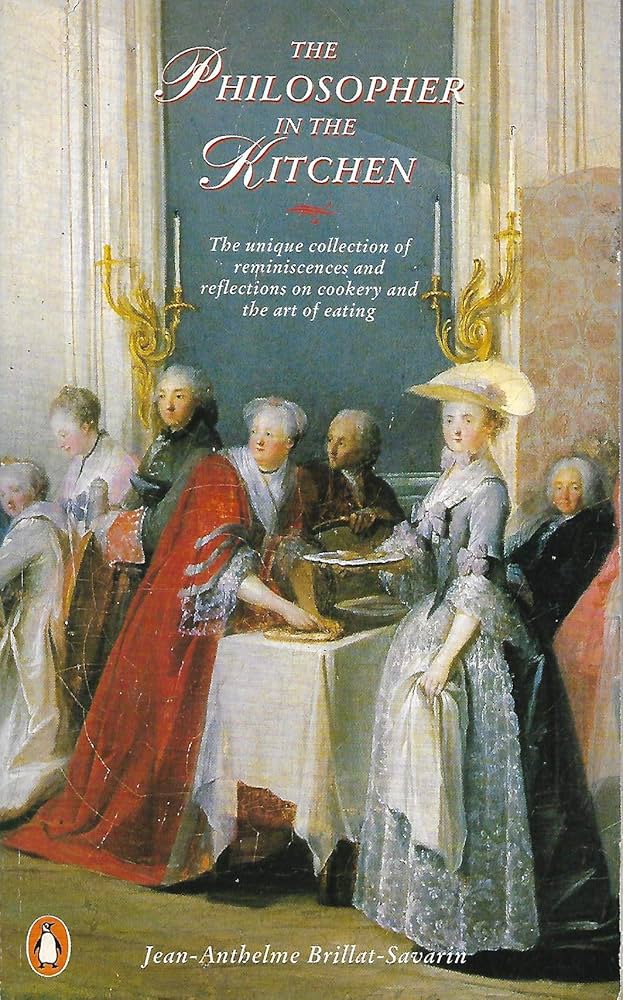

The Philosopher in the Kitchen

Author: Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

Translated by Anne Drayton (1970)

French Title: Physiologie du goût

Link: Internet Archive

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin was a French lawyer, politician, and noted gastronome. His part-memoir part-treatise, Physiologie du goût, is a prolegomena of sorts to the science of gourmandism. One may be tempted to think that this study of food and culture is merely a guide to gluttony. Brillat-Savarin is careful to dispel such notions. The glutton mindlessly consumes to excess, while the gourmand appreciates and enjoys to satisfaction. Far from a handbook to hedonism, this analysis of the art of the gourmand encompasses gastronomy, physical and mental health, and social interaction.

The book is written in short sections loosely divided into themes, mixing technical discussions of the author’s theory of food chemistry with recipes and tales from his eventful life. The writing is often witty and the translation by Anne Drayton is a pleasure to read. I was hooked from the beginning by the list of aphorisms that preface the main text; the best of which reads:

Dessert without cheese is like a pretty woman with only one eye.

In the section on physical and mental health, Brillat-Savarin discusses the importance of diet in maintaining health and longevity. He makes a case for the benefits of a low-carb diet for losing excess weight, becoming one of its first proponents.

There’s an amusing mention of a correlational health outcomes study by Louis-René Villermé from the prior year. This study finds that “good cheer is far from being harmful to health, and that, all things being equal, gourmands live longer than other men.” Elaborating on the methods:

He compared the various classes of society in which good cheer is habitual with those which are poorly fed, covering the entire social scale. He also considered the various quarters of Paris with one another according to their wealth, for it is well known that wide divergencies exist in this respect.

The most interesting section, however, is the discussion of restaurants near the book’s conclusion. Restaurants in the modern sense were a relatively recent innovation, appearing in Paris in the latter half of the eighteenth century and quickly spreading throughout Europe and beyond during the French Empire’s warring efforts.

The Spirit of the Age: Or, Contemporary Portraits

Author: William Hazlitt

Link: WikiSource

The conservative reaction to the French Revolution dampened liberal attitudes around the turn of the nineteenth century. This collection of essays captures this milieu through portraits of several prominent British figures, from philosophers to poets to MPs.

Outside of a few characters depicted as the embodiment of tyranny and injustice such the Tory MP Lord Eldon, Hazlitt’s general assessment is that each figure’s early work is superior to their later work due to their abandonment of liberal principles. Hazlitt is particularly critical in this regard to the Lake Poets.

In short bursts, Hazlitt’s style is engaging. The opening salvo sharply critiques Jeremy Bentham’s philosophical project as fantasy and navel-gazing. The discussion of Coleridge’s intellectual adventures demonstrates the breadth of Hazlitt’s interests. The profiles of various MPs give insight into the position of the intellectual in the political realm.

When read together, however, this collection grates on one’s mind. Hazlitt has a tendency to juxtapose figures and ideas as diametric opposites. For example, the article on long-time Edinburgh Review editor Francis Jeffrey contrasts the Whig-friendly Edinburgh Review with the Tory Quarterly Review. All that is right with the world is attributed to the Edinburgh and all the muck given to the Quarterly. To be fair, the Edinburgh Review is the better magazine in my estimation; yet, both are inferior to the Westminster.

Hazlitt can stretch his credibility to the point of becoming an unreliable narrator. The article on Walter Scott criticizes his conservative overtones through romanticizing the past; yet, when comparing Scott with Lord Byron, Hazlitt holds the former to be the greatest moralist of the age and the latter a phony liberal.

I most enjoyed the essays on Walter Scott, William Godwin, Horne Tooke, and James MacKintosh. I knew of Scott as the author of Waverley, the philosopher Godwin only as father to Mary Shelley, but was unaware of the interesting MPs: the jurist Tooke and the Scottish philosopher MacKintosh.

Philosophical Considerations on the Sciences and Savants

Author: Auguste Comte

Translated by Henry Dix Hutton (1877)

French Title: Considérations philosophiques sur la science et les savants

Publication: Le Producteur

Link: Internet Archive

Auguste Comte is a often presented as one of the villains in the history of social thought. Similar to Wittgenstein, there is the early Comte and the later Comte. The early Comte is interested in the history of thought and intellectual development and is often associated with the six volume Course of Positive Philosophy (1830-1842). It’s the later Comte associated with the System of Positive Polity (1851-1854) and his religion of humanity that is much reviled.

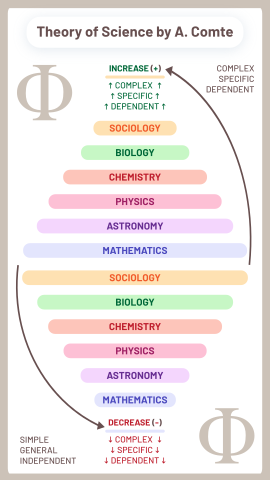

In this article, Comte introduces his law of three stages and the hierarchy of the sciences. The former holds that human intellectual development passes through three stages: theological, metaphysical, and positive. Theological thought is all encompassing and often anthropomorphized, attributing phenomena to supernatural beings. This mode of thought is rigid and allows little room for change. Metaphysical thought is still spooky but less centralized, allowing for the possibility of change. Positive thought is empirical, scientific, and decentralized and seeks to explain phenomena through general laws.

Comte argues that the sciences can be categorized into a hierarchy beginning with the natural sciences up through the social sciences, similar to other attempts to explain the unity of science. Fields of study in the hierarchy progress from bottom up with some fields being scientific while others are still spooky at a given time. In the early nineteenth century, physics and astronomy attained the status of a positive science, while the moral sciences were still largely theological and metaphysical, being dominated by Medieval theology and eighteenth century Enlightenment thought.

This leads to an interesting critique of encyclopedias and the organization of knowledge. Comte argues that such projects are only feasible once human thought has sufficiently developed; otherwise, two adjacent fields at different stages of development may offer mutually exclusive explanations for the same phenomena.

The article concludes with sketching a history of intellectual development. Early societies were theocracies, typified by Egypt, where there was no distinction between priest, philosopher, and state authority. Ancient Greece represented the transition to metaphysics with the distinction of the philosopher from the priest. This is illustrated by the differing philosophical attitudes of Plato and Aristotle. An antagonism between science and theology developed as they butted heads on social issues. Several attempts to reconcile the two under the auspices of theology e.g. by the Jesuits were at best temporarily successful. What remains is to create a social physics i.e. a positive social science. This, in turn, would lead to a reorganization of society in the hands of technocrats.

Mathematics

On the method of the least squares

Author: James Ivory

Publication: Philosophical Magazine

Link: T&F Online

Least squares is an estimation method that fits a line to a set of points that minimizes the sum of the squared distances from the points to the line and is a workhorse in statistics and machine learning. This method was introduced by Adrien-Marie Legendre in 1805 as a heuristic to correct for measurement error in astronomical data. Aside from an independent investigation from Robert Adrain in 1808, Carl Gauss and Pierre-Simon Laplace offered the first justifications for least squares in important publications from 1809 and 1810, where Gauss derived the normal distribution and Laplace proved the central limit theorem.

Ivory’s paper offers a few justifications for least squares and frames the problem in terms of reducing error from astronomical observations. Ivory begins by critiquing an approach from the early eighteenth century by Roger Cotes that correctly observed that averaging multiple noisy observations decreases error. The first two justifications are the most clearly developed. The first employs an analogy with levers and fulcrums to represent how each observation is weighted. The second is more reasonable and argues that least squares is principled and minimizes mean squared error.

from the Royal Society in 1814

Ivory is an interesting and tragic historical character. He was a Scottish mathematician of the first order and a chief exponent of the continental approach to analysis and mechanics and one of the first in Britain to use Leibniz’s notation for the differential and integral calculus. Despite receiving several awards from the Royal Society and even being knighted, Ivory was plagued by delusion and paranoia, which limited his contributions and resulted in controversies with other big names of the time.

On the Nature of the Function Expressive of the Law of Human Mortality, and on a New Mode of Determining the Value of Life Contingencies

Author: Benjamin Gompertz

Publication: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London

Link: JSTOR

Imagine you’re trying to determine whether or not a life insurance policy or an annuity is priced fairly. How might you go about this? A reasonable place to start is collecting data on how long people live and calculating a contingency table or an empirical distribution. Even if this sample is representative, this approach has several drawbacks, e.g., the estimated distribution is discrete and making the distribution more fine-grained comes at the cost of higher variance estimates. Calculating the present value of an instrument from a discrete distribution can be computationally expensive (especially using methods from the early nineteenth century).

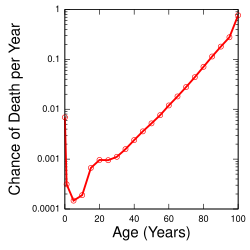

mortality rates (log scale) in the US in 2003.

Gompertz proposes a model for the mortality rate at age $x$ ($\mu_x$) that increases exponentially with age, now called the Gompertz Law of Mortality. In symbols, $\mu_x = Bc^x$, where $x$ is age, $B$ is the baseline mortality rate, and $c > 1$ is the acceleration of mortality. Much of the paper shows that the proposed model closely approximates various datasets for adulthood, except at very old age. This model provides several benefits. Being a continuous time model, calculating probabilities is as simple as integrating the mortality rate over the desired age range. Moreover, the estimation problem is reduced to two parameters $B$ and $c$ rather than the full empirical distribution.

While some may view life insurance as a bit of a morbid topic, Gompertz doubles down on the macabre by describing his model of the mortality rate as “a deterioration, or an increased inability to withstand destruction”.

International Relations

A Review of the Efforts and Progress of Nations during the Last Twenty-Five Years

Author: J. C. L. de Sismondi

Publication: Revue Encyclopédique

Translated by Peter Stephen Du Ponceau in The Port Folio (1825)

Link: HathiTrust

The period from the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth century was the age of revolutions. From Europe to the Americas and Africa, monarchies became less absolute - in some cases even overthrown - and power and wealth became more dispersed.

from the Online Library of Liberty

In this review, Sismondi surveys revolutions the world over. He characterizes this period as a conflict between two opposing forces: one pushing in the direction of Enlightenment ideas and greater individual liberty, and the other toward greater concentration of power. The former is the wave emanating from the overthrow of the ancien régime in France, and the latter is the conservative reaction.

Individual political movements run the gamut between these extremes; however, Sismondi identifies some patterns to help make sense of the aftermath. When revolutions come from within and capture the elusive public opinion, they tend to favor greater liberty and enfranchisement. In contrast, revolutions brought about by external actors tend to concentrate power, often in the hands of those same actors. Overall, however, the world is trending toward greater liberty and prosperity.

A review in the North American Review takes issue with some of Sismondi’s claims. Sismondi overplays the success of Enlightenment ideas in France; however, this is understandable, since Sismondi had to get his publication approved by the French censors. On the other hand, Sismondi underplays the success of such adoption elsewhere in Western Europe such as Germany and Italy. Perhaps, this was motivated by national rivalry. While I read Sismondi as relatively optimistic about Enlightenment ideals prevailing, the reviewer is even more so.

Letter to Mrs. Wheeler

Author: William Thompson

Link: Google Books

This letter to the political writer Anna Doyle Wheeler acts as the preface to Thompson’s Appeal of One Half of the Human Race. Thompson begins the letter by attributing the ideas proffered in the book as the joint product of himself and Wheeler. The core argument is that the position of women in society and the laws restricting their political rights are not only unjust but are suboptimal from an utilitarian perspective. By denying women education, political participation, and economic independence, society is squandering a vast reservoir of talent and potential.

This book is directly responding to a passage discussing representative democracy in James Mill’s Essay on Government for the Supplement to the Encyclopedia Britannica. Mill argues that, since subgroups of the population can represent the broader interest of the people, we should not extend political rights to women. This is a bit baffling to read, since Mill is a radical arguing for liberal reforms, and certainly rubs me the wrong way. I’m glad a response on this point exists! While I found it dragged on too long, this opening letter is a strong hook for the remainder of the book.

Misc

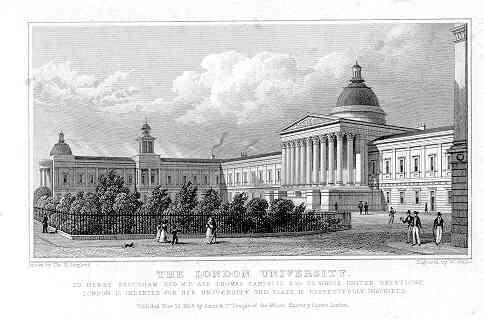

New University in London

Publication: Edinburgh Review

Link: Google Books

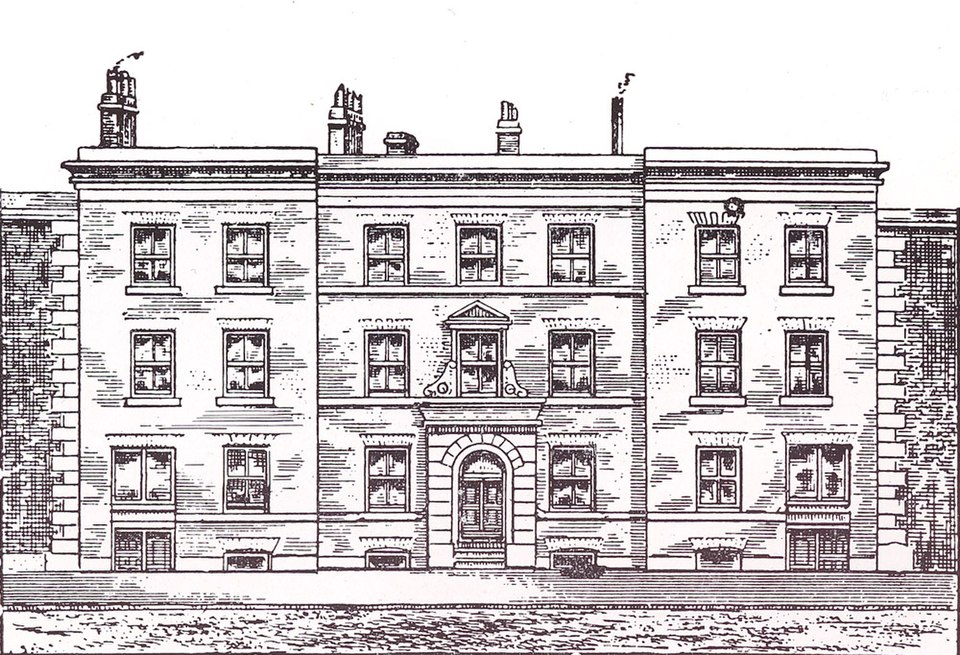

Since the eleventh century, Oxford and Cambridge were the only universities in England. With rise of the working class during the first industrial revolution, the early nineteenth century saw the founding of Mechanics’ Institutes and mutual improvement societies. In the 1820s and 1830s, several candidates popped up for a third university in England to meet the demand for education. This unsigned article discusses and advertises the founding of London University, now called University College London.

Thomas H. Shepherd (1828)

While the two university system may have made sense during the Middle Ages, the author argues that it is no longer the case. As the demand for education increased, Oxford and Cambridge were scarcely able to take on more students. The cost of attendance for room and board, tutors, and religious services were exorbitant and priced out many would-be students, an evergreen complaint. Without competition within England, educational standards had stagnated and not kept up with recent advances in knowledge. Moreover, the author cautions that sending young men far from home during their formative years is a recipe for debauchery.

London seems to be a natural fit for a university. Not only is it home to the Royal Society with its large pool of potential professors, but it has ample hospitals to justify a medical school. The author closes by advising that the proposed university was still raising funds. London University would open the next year in 1826.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee