An Utterly Incomplete Look at Research from 1874

This series looks at research from years past. I survey a handful of books and articles in a particular year from math, economics, philosophy, international relations, and other interesting topics. This project was inspired by my retrospective on Foreign Affairs' first issue from September 1922.

1874 is a pivotal year in intellectual history. Or, at least, it’s a year in which two important mathematical seeds were planted. Léon Walras’ mathematical approach to economics completed the trio of books that led to the marginal revolution and introduced general equilibrium analysis. Georg Cantor published his proof that the set of real numbers is uncountable that led to the development of set theory.

A common theme in the selections below is materialism versus idealism. John Tyndall’s address to the British Association argues that naturalistic approaches to philosophy and science have been stymied by spooky approaches throughout the history of thought. John Draper argues that science and religion are inherently at odds. George Henry Lewes pokes holes in the speculative reasoning of Hegelianism and contrasts it with the analytical approach of Lagrange. In the other direction, F. H. Bradley argues that the historian’s task is complicated by the subjectivity and fallibility of testimony, presumably compromising additional enterprises.

I most enjoyed reading two books: Henry Sidgwick’s The Methods of Ethics and William Stanley Jevons’ The Principles of Science. Sidgwick’s book is a comprehensive study of nineteenth century moral philosophy that argues for utilitarianism. Jevons’ book is a wide-ranging account of scientific reasoning that’s bursting with interesting ideas and argues for a logical account of induction. If I’ve missed anything interesting from 1874 that you enjoy, shoot an email my way at brettcmullins(at)gmail.com.

Economics

Elements of Theoretical Economics by Léon Walras

The Mathematical Theory of Political Economy by William Stanley Jevons

Lombard and Wall Streets by Gamaliel Bradford

Taxation on the Working Classes by Thomas Edward Cliffe Leslie

Philosophy

The Methods of Ethics by Henry Sidgwick

The Presuppositions of Critical History by F. H. Bradley

The Anaesthetic Revelation and the Gist of Philosophy by Benjamin Paul Blood

Math

On a Property of the Set of Real Algebraic Numbers by Georg Cantor

On the problem of the eight queens by James Whitbread Lee Glaisher

International Relations

A Modern Financial Utopia by David A. Wells

The Metaphysical Basis of Toleration by Walter Bagehot

Philosophy of Science

The Principles of Science by William Stanley Jevons

Address Delivered Before the British Association by John Tyndall

On Professor Tyndall’s Recent Address by Thomas Davidson

On the Hypothesis that Animals are Automata, and its History by Thomas Huxley

Mind and Body by William Kingdon Clifford

Lagrange and Hegel: The Speculative Method by George Henry Lewes

The Great Conflict by John William Draper

The Limits of our Knowledge of Nature by Emil du Bois-Reymond

Other Topics

Universities: Actual and Ideal by Thomas Huxley

Economics

Elements of Theoretical Economics: Or, the Theory of Social Wealth

Author: Léon Walras

French Title: Éléments d’Économie Politique Pure, ou Théorie de la richesse sociale

Translated by Donald A. Walker and Jan van Daal (2014)

Link: Google Books

The marginal revolution in economics is typically attributed to the work of three economists in the early 1870s: William Stanley Jevons, Carl Menger, and Léon Walras. Each independently developed the concept of marginal utility and used it to explain the determination of prices. Though they arrived at similar outcomes, there are divergences in approach.

by Felix Dupuis (1862)

Walras’ Éléments is the more mathematically rigorous of the three. Somewhat akin to Lagrange’s formalization of Newtonian mechanics, Walras’ approach allowed one to reason about economic phenomena without resorting to the use of diagrams or verbal reasoning. Walras pioneered the general equilibrium approach that showed how prices for all goods and services in an economy could be determined simultaneously, thereby accounting for the interdependence of markets. The general equilibrium approach would not reach its peak influence until work by Arrow, Debreu, etc. in the mid-twentieth century.

I came away from reading this one a bit underwhelmed. Perhaps, I’ve not read as much classical economics such as Mill’s Principles of Political Economy (1848) to appreciate what’s going on. Perhaps, instead, it’s the translation. I read the 2014 translation of the third edition from 1896, which is largely an expansion of the original. Another English translation exists from 1954 by William Jaffé; however, this is translated from the fifth edition from 1926, sixteen years after Walras’ death, and contains substantial modifications of the original ideas.

The Mathematical Theory of Political Economy

Author: William Stanley Jevons

Publication: Journal of the Royal Statistical Society

Link: Google Books

This article introduces Léon Walras’ Éléments d’Économie Politique Pure in the context of Jevons’ work on the mathematical approach to economics. Note that Jevons is likely as motivated by establishing priority as with promoting the mathematical approach. While this approach is innovative, it’s not strictly due to its mathematical character; the theories of classical economists from Smith to Ricardo and Mill dealt with quantity and magnitude in the form of prices, taxes, values, rents, etc.

What differentiates the current approach from classical economics is, rather, the treatment of utility.

Economists, with few exceptions, have described utility as if it were a fixed and invariable quality of a substance, like its colours, density, hardness, or conductivity.

Jevons holds, instead, that utility depends on circumstance and personal idiosyncrasies. The crux of this approach is that utility diminishes with the quantity of a good consumed and that decisions ought to be made at the margins. This observation explains why a third pair of shoes is less valuable than the first and why widely abundant goods such as water are valued less than diamonds. This approach would come to be known as marginalism.

Lombard and Wall Streets

Author: Gamaliel Bradford

Publication: North American Review

Link: JSTOR

This is a review of Walter Bagehot’s examination of banking in the UK Lombard Street from 1873. Bradford criticizes Bagehot from two directions. The first is that Bagehot provides insufficient context to the reader in an effort to appear non-partisan. Debates over the convertibility of the currency raged in England since the turn of the nineteenth century. This culminated in the Bank Act of 1844 (also called the Peel Act after Prime Minister Robert Peel), which restored convertibility alongside a wholesale reform of the banking system.

Bradford argues that Bagehot views banks as another merchant in the market that are affected by external shocks like other firms: prospering in good times and attempting to weather bad times. In contrast, Bradford sees banks as intimately connected to the business cycle.

The banks are endowed with vast privileges to their own great profit, and with extreme liability to abuse to the great detriment of the public; and that the government is especially bound to protect the public from such abuse; in short, that deposit currency is just as much a subject of government regulation as note currency; and that in such regulation is to be found the effective amendment of the Act of 1844.

The Incidence of Imperial and Local Taxation on the Working Classes

Author: Thomas Edward Cliffe Leslie

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: Google Books

from Punch Magazine

February 27, 1969

For nearly two decades from the 1850s to the early 1870s, successive governments in the UK sought to reduce taxes and end the income tax; however, budget shortfalls arising from one-off outlays such as the Crimean War kept it in place. Both party leaders in the run up to the 1874 election, Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone, campaigned on ending the income tax. Though Disraeli and the Conservatives won, they kept the tax.

This article discusses how taxation in the UK affects the working class. While the tax system was thought to be favorable to the poor, Leslie argues that taxes in aggregate are regressive i.e. the effective tax rate decreases with income. Moreover, Leslie charges that the tax system does not account for one’s ability to pay but, rather, is based on the average profit of workers, a limitation inherited from the classical economists. Such taxes become particularly burdensome for workers in volatile industries.

Philosophy

The Methods of Ethics

Author: Henry Sidgwick

Link: Internet Archive

The landscape of moral philosophy in the nineteenth century can be divided into three accounts: egoism, utilitarianism, and intuitionism. Egoism considers how one’s actions affect one’s outcomes, utilitarianism considers how one’s actions affect everyone’s outcomes, and intuitionism considers the acts themselves. The latter account also posits a faculty for intuiting the rightness or wrongness of a given action. The Methods of Ethics is an in-depth discussion of these accounts and an extended argument for utilitarianism.

Sidgwick employs two main lines of argument: examining internal consistency and comparing to common sense notions of morality. The first is self-explanatory and presents problems for intuitionism since intuitions vary by time and place, among other issues. The second is more interesting since Sidgwick views ethical theories as guides to behavior (or, rather, as decision theories). This conception of moral philosophy is more prescriptive and positive than normative.

Egoism can be easily dismissed as not according with common sense. Common sense often approximates utilitarianism, which accounts for why moral conceptions differ in past times and other places. Sidgwick argues that intuitionism and utilitarianism are compatible - at least with respect to a particular place and time. Our intuitions evolve as civilization and its circumstances change.

This book had a long life receiving its seventh edition in 1907 and outlived Sidgwick, who died in 1900. While the seventh edition is most readily available today, I read the first edition, owing to a substantial revision with the second (1877). Note that the two editions that followed Sidgwick’s death were edited by E. E. Constance Jones.

This is an excellent study of moral philosophy and belongs among other great books in the area such as John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice (1971) and David Gauthier’s Morals by Agreement (1986).

The Presuppositions of Critical History

Author: F. H. Bradley

Link: HathiTrust

by R.G. Eves, 1924

This long essay analyzes the task of the historian. Unlike the scientist who makes inferences based on reproducible observations under experimental conditions (at least in the ideal), the historian relies on testimony and is situated in a particular cultural and civilizational setting. What differentiates historical testimony from scientific observation is that the latter is impersonal insofar as it abstracts away from the biases of the observer. The former, however, may be framed by the concerns of the present or is flavored by the observer’s proclivities. Bradley discusses the possibility of a critical history that relies on testimony but is impersonal and, thereby, trustworthy. Bradley’s core idea is reminiscent of Herbert Spencer’s view of the prospects for social science.

While Bradley’s writing style can be poetic, it is more often than not frustrating and borders on obscurantist. This surely seems purposeful as both the preface and appendices A through D are both more clearly written and better convey his argument than the main text. Appendix A, in particular, compares the task of the historian to that of a painter replicating a painting of a scene. The painter only has access to the scene through the original painting and has a personal style that differs to some degree from the artist of the original through cultural differences, personal taste, or artistic ability. Appendix E, however, muddies the water by dragging his argument into the morass of Hegelianism.

The Anaesthetic Revelation and the Gist of Philosophy

Author: Benjamin Paul Blood

Link: Internet Archive

This pamphlet collects two related essays: one long, The Gist of Philosophy, and the other short, the Anaesthetic Revelation. The former argues that approaches to metaphysics fail to be a complete description of reality from Plato, Aristotle, and the metaphysics of the ancients to Kant, Fichte, and German Idealism. More so than with Bradley, Blood has fleeting moments of clarity that quickly turn impenetrable. Some passages even read as if they were translated into another language and back. The Anaesthetic Revelation refers to a sort of ineffable resolution to metaphysical problems that Blood experienced while experimenting with Nitrous Oxide. Perhaps, the unintelligible quality of Blood’s writing can be attributed to the laughing gas.

William James wrote a review in The Atlantic. In three paragraphs, James better communicates Blood’s argument than the original pamphlet. He summarizes The Gist of Philosophy as Blood wading deep into metaphysics to free himself from it. James then connects the euphoric state Blood experienced while under Nitrous Oxide with Nirvana and other such states described by religious traditions. This work influenced James’ own Varieties of Religious Experience (1902).

Math

On a Property of the Set of Real Algebraic Numbers

Author: Georg Cantor

Publication: Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik

German Title: Über eine Eigenschaft des Inbegriffes aller reellen algebraischen Zahlen

Translated by William Ewald in From Kant to Hilbert, Vol. II (1996)

By the latter half of the nineteenth century, a rigorous foundation for real analysis was developing with formal approaches to continuity, limits, differentiability, integration, convergence criteria for infinite series, etc. from mathematicians such as Bolzano, Cauchy, Riemann, and Weierstrass. This short paper takes a big step in understanding the continuum by proving that the real numbers are uncountable.

Rather than the well-known diagonalization argument, Cantor argues that, for any sequence of real numbers and any non-trivial interval, there is an element of the interval not in the sequence, which shows that the reals cannot be enumerated. Cantor observes that this “turns out to be the reason why sets of real numbers which form a so-called continuum cannot be mapped one-to-one onto [the natural numbers]; thus I have discovered the difference between a so-called continuum and any set like the totality of real algebraic numbers.”

On the problem of the eight queens

Author: James Whitbread Lee Glaisher

Publication: The Philosophical Magazine

Link: Google Books

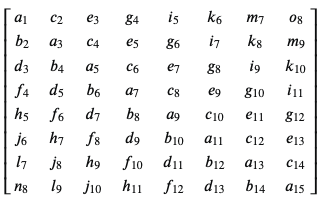

The eight queens problem is to count the number of ways of placing eight queens on a chessboard such that no queen is threatened by another. This paper discusses a method for solving this problem and generalizations to $n$ queens on an $n$ by $n$ chessboard from a German paper by Siegmund Günther.

Consider the chessboard as a matrix and code each entry of the matrix with two indices: the first is a letter denoting the upper-left to bottom-right diagonal and the second is the $\ell_1$ or taxicab distance from the upper-left corner entry. See the example to the right. By computing the determinant of the matrix and eliminating any term that repeats a letter or distance, the remaining terms are the solutions to the problem. There are 92 solutions to the original problem.

This paper became a cannon English-language reference for the eight queens problem and inadvertently spread misinformation about its history. Glaisher attributed priority to Carl Friedrich Gauss who learned of the problem in 1850; however, the problem was first proposed by Max Bezzel in a German chess magazine in 1848. Gauss offered some approaches but did not study the problem extensively; however, his solutions were communicated to another chess publication anonymously. The problem was solved by Giusto Bellavitis in 1861 and Carl Jaenisch in 1862.

International Relations

A Modern Financial Utopia

Author: David A. Wells

Publication: The Atlantic Monthly

Link: The Atlantic

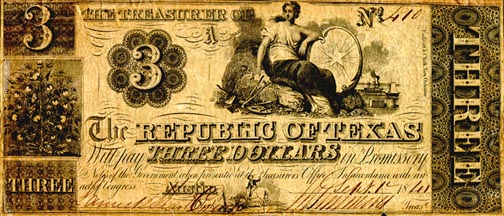

For ten years beginning in 1836, the Republic of Texas was an independent nation. During its brief existence, several attempts to build and sustain a currency were tried, made all the more urgent by the banking crisis in the United States that began in 1837 and the fact that Texas possessed little to no capital other than land.

One such attempt in 1837 that briefly stuck was the issuance of interest-bearing treasury notes. The interest these notes paid were a sufficient inducement to be held, and the notes were in small enough denominations to facilitate trade. In the following year, the government authorized the printing of additional notes - without bearing interest - which precipitated the rapid depreciation of the currency to be essentially worthless by 1842.

Wells argues that this episode illustrates the maxim that fiat currencies lead to national disasters via fiscal irresponsibility. On this issue, Wells was influenced by the economist William M. Gouge who was influential among policymakers including the Jackson administration.

The Metaphysical Basis of Toleration

Author: Walter Bagehot

Publication: The Contemporary Review

Link: Google Books

This article argues that states with a sufficiently developed culture should allow free speech or, rather, the free public expression of ideas. This does not extend to actions; Bagehot isn’t advocating anarchy! Rather, he presents a sort of marketplace of ideas view such that society will tend to weed out the bad ideas and align on beneficial norms, though society is not infallible and may even be prone to suboptimality. Imposing views by force through persecution is not sustainable in the long term.

Bagehot argues that the urge to persecute one’s fellow man is rooted in early humans’ need for stability and conformity, specifically to combat the widespread belief that the bad actions of one member of the community could cause divine punishment for the whole community.

Philosophy of Science

The principles of science: a treatise on logic and scientific method

Author: William Stanley Jevons

Link: Internet Archive

A prominent debate in nineteenth century philosophy of science concerned the role of deduction in scientific reasoning. William Whewell proposed that scientific inference consists of induction to form general laws and deduction to apply or test these laws in particular cases. John Stuart Mill, on the other hand, argued that scientific inference is purely inductive and empirical.

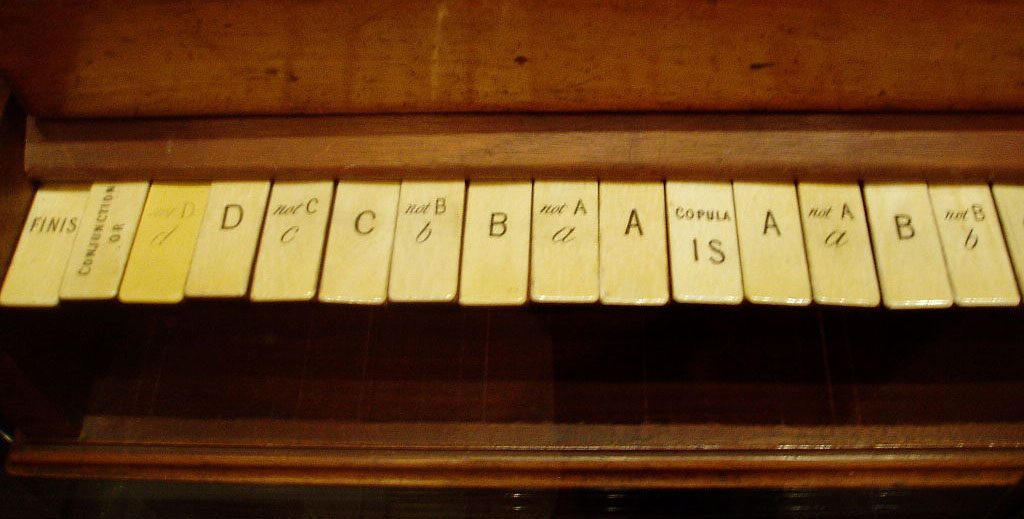

This book develops a wide-ranging account of scientific reasoning, in line with Whewell and unified by what Jevons’ calls the Law of Identity. While the notion of logical identity seems vacuous, it serves as the bedrock for Jevons’ analysis of various topics: logic, arithmetic, probability, induction, and the philosophy of science.

Jevons begins with an odd account of predicate logic, where formulas are constructed from the conjunction of predicates. We can think of a conjunction of predicates as the intersection of the extension of each predicate i.e. the subset of the domain that satisfies all predicates in the conjunction. He introduces operators such as or to join conjunctions into formulas. The accompanying unwieldy system of deduction is equivalent to reasoning about the extension of the formulas, though with a limited set of inference rules. At one point, the existential quantifier is even expressed as a predicate.

Jevons treats induction as the inverse of deduction. He draws an analogy to calculus, arguing that deductive inference, like calculating derivatives, is a more straightforward process than inductive inference, which resembles integration. Given that induction with certainty is too epistemologically demanding, he argues that general laws, such as those in natural science, can only be established probabilistically.

from the Online Library of Liberty

Jevons gets a lot of milage out of the Law of Identity. In probability, it pops up as the principle of indifference, which says that all possible outcomes should be considered equally likely absent evidence favoring any outcome. This implies an epistemic interpretation of probability, where probabilities represent uncertainty or ignorance.

There’s so much going on in this book that my treatment above just scratches the surface. Jevons’ approach is idiosyncratic but interesting and bursting with ideas. With that being said, I find it difficult to recommend this book in general. I’m surprised, though, that I had never heard of this book before digging it up while planning this project.

Address Delivered Before the British Association Assembled at Belfast

Author: John Tyndall

Link: Google Books

While evolution was a hot and controversial topic in the 1870s, it was far from the scientific consensus. Many eminent scientists of the day were decidedly conservative with respect to religious matters. Tyndall, an accomplished scientist in his own right, belonged to a circle called the X Club who advocated for naturalism and a demarcation between science and dogmatic religion.

In 1874, Tyndall was elected president of the British Association - a counterpart to the Royal Society - and delivered the keynote speech at the annual meeting. In this speech, Tyndall traces the history of philosophy as a conflict between naturalism and religious, spooky, and obscurantist approaches. Thus, we find Democritus, Epicurus, and other atomists advocating for a sort of materialist view, while Plato and Aristotle shift the focus to cumbersome metaphysics. In the Middle Ages, naturalistic approaches to philosophy were stamped out of Western Europe by Christian dogma, Neoplatonism, and Scholasticism but were continued elsewhere by Islamic scholars.

In the seventeenth century, we have Francis Bacon, Pierre Gassendi, and others beginning to advocate for experimentalism. The following century brings us Joseph Butler’s rejoinder in favor of Christian belief. The nineteenth century through the present saw the development of evolutionary theory from Darwin and Wallace’s biological evolution of species to Herbert Spencer’s social evolution.

The moral of this chronology is that naturalistic approaches to philosophy have met with pushback at every turn in the history of ideas, impeding our understanding of the natural world. Tyndall implores the reader (or listener rather) to dispense with dogmatic views that infringe on the accumulation of knowledge. This applies equally to religious sentiment - he cites Draper’s History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science (1874) - and idealist metaphysics - he cites Kant and Fichte. The latter is particularly ironic, since British idealism would become the dominant force in British philosophy for the next half century. In fact, the first major work from F. H. Bradley, The Presuppositions of Critical History, was published the same year.

On Professor Tyndall’s Recent Address

Author: Thomas Davidson

Publication: Journal of Speculative Philosophy

Link: JSTOR

A familiar trope in the history of intellectual thought is scientists doing philosophy badly and vice versa. In this response to John Tyndall’s sensational speech at the British Association, Davidson hammers Tyndall’s account of the history of philosophy as amateurish. In one instance, Tyndall mixes up the chronology and contributions of some pre-Socratic philosophers such as Pythagoras and Empedocles and, in general, Tyndall’s account of Aristotle is questionable.

Davidson charges that Tyndall is too reliant upon secondary sources such as George Henry Lewes’ account of Aristotle as a scientist and William Whewell’s history of science from 1837. Regarding external world skepticism, Tyndall punts to Herbert Spencer’s common sense account. While Davidson sympathizes with Tyndall’s aim, he found this talk and the accompanying buzz to be more harmful than not.

On the Hypothesis that Animals are Automata, and its History

Author: Thomas Huxley

Publication: Nature

Link: Nature

Just as we think of Descartes as primarily a philosopher and secondarily a mathematician today, he was held in similar regard in the late nineteenth century. In addition to his other work, Descartes made many contributions to physiology such as proposing a mechanism for the nervous system in terms of “animal spirits”. Much of his proposals were correct in broad strokes and were developed by physiologists over the following two centuries.

by Daniel Toretsky, 2013

One hypothesis that didn’t see wide adoption is that animals are automata i.e. animals behave mechanistically without free will or even consciousness. Huxley notes that this has strong ethical implications for how we think about animals. After presenting some dubious case studies, Huxley argues that we can at best claim that animals are conscious automata, since ruling out consciousness is too difficult.

This is the transcript of a talk given at the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Belfast in 1874, the same meeting as John Tyndall’s controversial address. An article version of Huxley’s talk was published in the Fortnightly Review.

Mind and Body

Author: William Kingdon Clifford

Publication: Fortnightly Review

Link: HathiTrust

Joesph Meehan

This article introduces a materialist, epiphenomenal view of the mind which reduces all mental states to brain states. While there are both physical and mental facts, no mental facts are needed to causally explain physical facts. Moreover, each mental fact has a corresponding physical fact, so even mental facts can be explained physically. Clifford supports this assertion by briefly surveying the brain and nervous system.

In contrast to Thomas Huxley’s view of automata, Clifford argues that humans are automata and confronts the objection that being an automaton is incompatible with free will. If free will is understood to be that one can reason and act without outside influences, then being an automaton is exactly what it means to have and exercise free will.

Lagrange and Hegel: The Speculative Method

Author: George Henry Lewes

Publication: The Contemporary Review

Link: Google Books

This is an excerpted chapter from the second volume of Lewes’ Problems of Life and Mind (1874). Lewes argues against Hegelian-style arguments by comparing the speculative method with Lagrange’s Mécanique analytique (1788). Lagrange’s treatment of mechanics synthesized much prior work in natural philosophy. Without relying on diagrams or other tools, he presented mechanics as a coherent algebraic system. Hegel’s approach sought to capture the mechanics of thought rather than the material world.

Hegel’s aim was to reduce the theory of the universe and the solutions of various problems to a single principle - namely the dialectical movement of contradiction in which one idea successively evolved another by union with its opposite.

Both methods are deductive, making inferences about the world from axioms and initial conditions. The difference, Lewes argues, is that Lagrange’s theory better corresponds to reality than Hegel’s. In both settings, we pull a state of the world into a model, reason to an outcome, then project back into the world. A perfect model, then, is isomorphic to the real world. This difference can be attributed to the motivations of the respective systems. The axioms and principles of Lagrange’s mechanics are (largely) empirically motivated rather than logically motivated. The scope of their approaches varies as well. Whereas Lagrange models motion, Hegel sets himself at the more ambitious task of modeling everything.

The Great Conflict

Author: John William Draper

Publication: Popular Science Monthly

Link: WikiSource

This is the preface to History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science (1874), which advances the conflict thesis that there’s an inherent intellectual conflict between science and religion, particularly Roman Catholicism. Draper characterizes the history of intellectual thought as a tug and pull between these two modes:

The history of Science is not a mere record of isolated discoveries; it is a narrative of the conflict of two contending powers, the expansive force of the human intellect on one side, and the compression arising from traditionary faith and human interests on the other.

This analysis is timely as science and technological pursuits supplant religious arguments as the basis of governmental policy.

Ecclesiastical spirit no longer inspires the policy of the world. Military fervor in behalf of faith has disappeared. Its only souvenirs are the marble effigies of crusading knights, reposing on their tombs in the silent crypts of churches.

The Limits of our Knowledge of Nature

Author: Emil du Bois-Reymond

Publication: Popular Science Monthly

Link: WikiSource

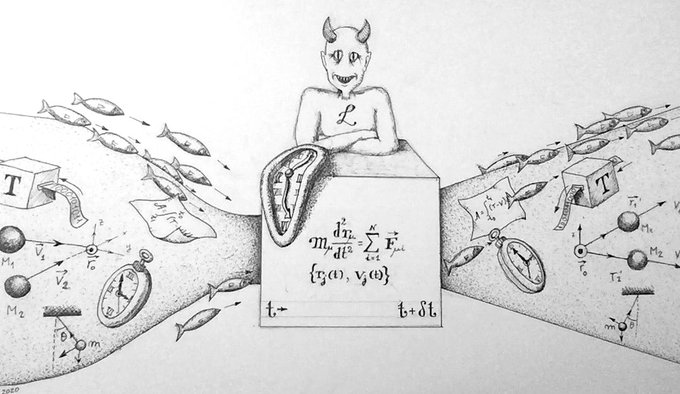

In Laplace’s A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities (1814), he imagines a mind that knows the position and velocity of every atom in the universe as well as the equations governing their behavior. Laplace posits that such as mind - or as it’s now called Laplace’s demon - can determine the events of the past as well as predict the future with the clockwork regularity of astronomical events.

Du Bois-Reymond disputes this sort of causal determinism by arguing that there are fundamental limits on what can be learned empirically, expressed by the motto “ignoramus et ignorabimus”. He points to two “incomprehensibles”: a fundamental account of matter and the mind-body duality. The Newtonian view of physics at the time viewed matter as divisible and extended in absolute space. But the idealized view of matter is as constructed from indivisible atoms that do not occupy space or, rather, are points in space. There have been several attempts to reconcile the mind and body such as Descartes’ causal interaction through the pituitary gland, Leibniz’s pre-established harmony, and the contemporary epiphenomenalism.

Other Topics

Universities: Actual and Ideal

Author: Thomas Huxley

Publication: The Contemporary Review

Link: Google Books

This is the transcript of the inaugural speech given by Huxley as Rector of the University of Aberdeen. Huxley offers a vision of higher education in Britain that includes the natural sciences alongside the arts. Aberdeen and other ancient universities in Britain still largely followed a curriculum around the trivium and quadrivium and didn’t have space for the experimental sciences. For instance, Aberdeen didn’t have a faculty of science; rather, scientists found their way into professional studies, particularly medicine.

the late nineteenth century

For Huxley, it’s not sufficient to require instruction in the natural sciences without an experimental and research component. Though only mentioning it once, he is undoubtedly influenced by the German model, which was seen as the best way to produce scientific knowledge. We see much of Huxley’s vision enacted today. As with much writing on higher education, we’re reminded that some experiences are evergreen: Huxley complains of how students are increasingly ill prepared for university education by the lax standards of secondary schools.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee