An Utterly Incomplete Look at Research from 1875

This series looks at research from years past. I survey a handful of books and articles in a particular year from math, economics, philosophy, international relations, and other interesting topics. This project was inspired by my retrospective on Foreign Affairs' first issue from September 1922.

The Fortnightly Review was a prominent British periodical in the 1870s, edited by John Morley, publishing articles on a wide range of topics including literature, philosophy, politics, and economics. A quick perusal of the selections below illustrates that the Fortnightly had an excellent year in 1875. Once I started digging in, I found more interesting articles than I had time to read, particularly in the first six issues (January to June). Not only do the topics heavily overlap with those covered in this project, but the articles are generally well-written and often thread the line between academic rigor and popular style. To a modern reader, this means that they are complex enough to have something interesting to say but accessible enough to figure out the context.

Looking more broadly, we can see two themes from this year’s selections. Several articles probe at the boundary where empirical science ends and metaphysics begins. John Tyndall argues that it is not outside of the scientist’s purview to discuss cosmological questions such as the origin of the universe. William Kingdon Clifford outlines the limits of applying scientific laws to predict both the distant past and remote future. W. R. Greg asks whether there are truths that cannot be discovered through human faculties.

In economics, there is a clear embrace of the subjective theory of value. William Stanley Jevons’ popular account of the institutions facilitating exchange presents the subjective theory of value as the theory of value. George Darwin reconciles John Elliott Cairnes’ cost-of-production theory of value with Jevons’ marginal utility theory. In an odd article, Henry Dunning Macleod argues that political economy is the science of exchange, best analyzed through the subjective theory of value.

There are two books I’d like to revisit at some point. I didn’t have a chance to read Cary Eggleston’s first-hand account of the American Civil War, A Rebel’s Recollections, initially published serially in The Atlantic the year prior. Additionally, I ran out of time and was not able to finish On Miracles and Modern Spiritualism from Alfred Russel Wallace, though I cover the opening essay below.

If I’ve missed anything interesting from 1875 that you enjoy, shoot an email my way at brettcmullins(at)gmail.com.

Economics

Money and the Mechanism of Exchange by William Stanley Jevons

A New Standard of Value by Walter Bagehot

Karl Marx and German Socialism by John MacDonell

Theory of Exchange Value by George H. Darwin

What Is Political Economy? by Henry Dunning Macleod

Philosophy

The Scottish Philosophy by James McCosh

Mr. Spencer on Social Evolution by John Elliot Cairnes

Can Truths be Apprehended Which Could Not Have Been Discovered? by W. R. Greg

A Recent Work on Cosmic Philosophy by Frederick Pollock

Mathematics

On the Integration of Discontinuous Functions by Henry John Stephen Smith

International Relations

The European Situation by Émile de Laveleye

A Note on Representative Government by Thomas Hare

The Liberal Eclipse by John Morley

Philosophy of Science

An Answer to the Arguments Against Miracles by Alfred Russel Wallace

The First and Last Catastrophe by William Kingdon Clifford

Reply to the Critics of the Belfast Address by John Tyndall

Miscellaneous

Are Languages Institutions? by William Dwight Whitney

Life Insurance by Simon Newcomb

Economics

Money and the Mechanism of Exchange

Author: William Stanley Jevons

Link: HathiTrust

This book bills itself as a prolegomenon to Walter Bagehot’s Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market (1873), one of the first popular books to describe the banking system and liquidity crises; however, it’s much more than that. The first several chapters are a (rather speculative) anthropological look at the origin and nature of money and exchange. Next, we move to a history of coins and currency. Once commerce becomes sufficiently widespread, different forms of currency such as token and representative currencies as well as various bills and bonds are used alongside commodity money, e.g., gold coins, out of convenience. This raises the question of what money is and how liquid an asset must be to be considered money. Similar to what one may find in an introductory economics text today, Jevons notes that there are several notions of money depending on how liquid we want it to be (and we usually want it to be rather liquid).

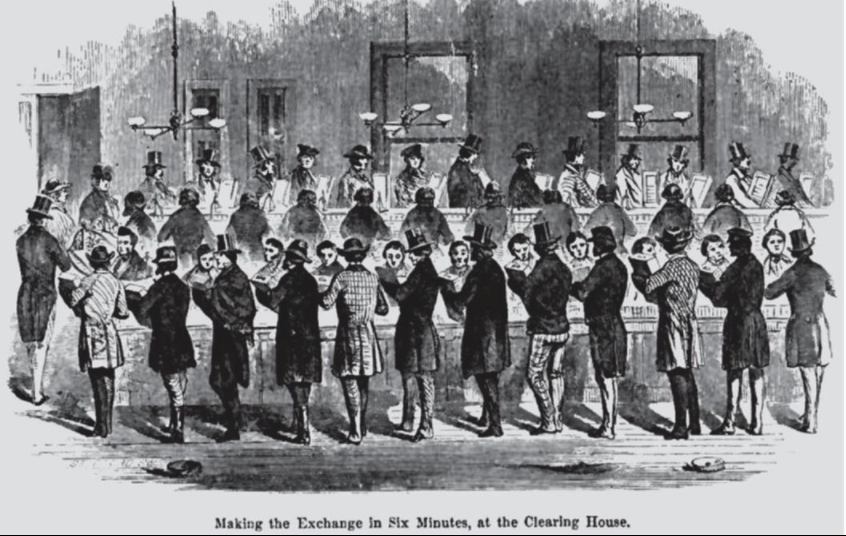

The most interesting part - and the part most worth reading today - describes the banking system through simple examples and introduces the relatively recent innovation of clearing houses, venues for settling checks and other sorts of transactions between banks. While these institutions are depicted as chaotic as the New York Stock Exchange trading floor prior to the millennium, they greased the wheels of the financial system by providing structure and lessening the need to exchange physical currency among banks. Outside of some minor suggestions, Jevons leaves the questions of policy for Bagehot.

A New Standard of Value

Author: Walter Bagehot

Publication: The Economist

Link: HathiTrust

Bagehot responds to an idea for an improved standard of value near the conclusion of William Stanley Jevons’ Money and the Mechanism of Exchange (1875). A standard of value is a common unit for measuring the value of goods and services, usually in the form of currency. The conventional wisdom in the nineteenth century was that coined precious metals, often gold or silver, were the appropriate standard of value. Jevons argued that this leads to unnecessary economic volatility because changes in the value of the commodity backing a currency often necessitates price changes with cascading effects, bankrupting some and delivering a fortune to others. Gold, in particular, had been on a price rollercoaster over the prior two centuries.

Jevons’ suggests backing currency by a basket of goods rather than a few precious metals, a precursor to CPI or other price indices. If the goods composing the basket are sufficiently uncorrelated, then the resulting standard of value would be stable. Bagehot finds the idea wholly impractical. Eliminating a common conversion between currencies would impede international trade and particularly harm London since a large portion of international payments flow through the city. Since commodities regularly experience fluctuations in value, it would be difficult to calculate at any time how much the currency was worth, especially for specifying contracts or settling debts. Moreover, standards on the quantity of the basket goods would need to be defined and enforced.

Karl Marx and German Socialism

Author: John MacDonell

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: Google Books

This article seeks to introduce the socialist ideas of Karl Marx to a broader audience. In the 1870s, Marx was overshadowed by Ferdinand Lassalle, who was widely seen as the sole leader of German socialism, though Lassalle died in 1864. Marx’s ideas differed significantly from Lassalle’s. Marx argued that the movement from capitalism toward socialism transcended the state, while Lassalle emphasized the state’s central role in reform. MacDonell offers a critical sketch of Marx’s economic ideas as one of pessimism and protracted misery for the working class followed by extreme optimism for revolution and the future.

MacDonell sought to improve discourse around Marx’s ideas. English economists largely dismiss Marx’s work as “puerile” and based on unreasonable assumptions, while converts adhere to Marx’s teachings beyond all reason. MacDonell thought we shouldn’t throw out the observation that unfettered industry can worsen the lives of the working class along with Marx’s economic theories. This article is particularly timely given the founding of the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany the same year. The party’s platform, the Gotha Program, sided with Lassalle’s ideas emphasizing the central role of the state, which Marx criticized in his Critique of the Gotha Programme, published later by Fredrick Engels in 1891. Socialism was a thorn in the side of the recently unified German empire; though, it was one concern among many.

Theory of Exchange Value

Author: George H. Darwin

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: Google Books

John Elliott Cairnes is considered one of the last classical political economists and passed away in 1875 soon after this article was published. Darwin seeks to reconcile Cairnes’ understanding of exchange value based on relative costs of production, developed in Cairnes’ Some Leading Principles of Political Economy Newly Expounded (1874), with William Stanley Jevons’ marginal utility theory. Darwin provides a clear, intuitive statement of subjective utility and diminishing marginal utility through examples such as the diamond-water paradox.

from the Online Library of Liberty

Cairnes views exchange value between two commodities as proportional to the ratio of their total costs of production. Darwin observes that this follows as a consequence of Jevons’ system assuming perfect competition, i.e., where prices equal the cost of production. Jevons’ “equation of exchange” shows that the utility maximizing rate of exchange between two commodities - understood as the ratio of their marginal utilities and today called the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) - is equal to the ratio of their prices, a standard result in modern consumer theory.

What Is Political Economy?

Author: Henry Dunning Macleod

Publication: The Contemporary Review

Link: HathiTrust

The dominant conception of classical political economy in the 1870s was “the consumption, distribution, and value of wealth”. Macleod takes issue with this account arguing that past writers varied significantly on their understanding of all four technical terms. Some examples: François Quesnay, whom Macleod regards as the rightful founder of political economy, held that all wealth is agriculture. Adam Smith held that labor determined value in some places and that the market determined value in others. John Stuart Mill is portrayed as hopelessly confused about the meaning of terms.

Macleod prefers a definition he attributes to Richard Whately: “the science of exchange”. This account builds a scientific basis for economics alongside established sciences such as mechanics, the science of motion, and optics, the science of light. Macleod begins the article oddly by claiming that his earlier work started a revolution in economic thought, thereby implicitly equating himself with other revolutionary thinkers such as Newton. I first thought he was taking claim for the marginal revolution; however, Macleod does not view the marginal utility principle as significant in his history of economic thought. Perhaps, he was simply talking about the subjective theory of value instead.

Philosophy

The Scottish Philosophy: Biographical, Expository, and Critical from Hutcheson to Hamilton

Author: James McCosh

Link: Internet Archive

The Scottish philosophy refers to an approach to philosophical problems developed in Scotland during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This book is part-encyclopedia, part-narrative history of its development. McCosh advances the idea that the Scottish school is defined by its focus on human psychology, its use of inductive methods, and its connection with the Christian religion.

Francis Hutcheson is the most important precursor to the story. Writing in the early eighteenth century, Hutcheson develops a moral theory based on the existence of a moral sense or faculty that guides one’s behavior. Next, we’re introduced to our first antagonist: David Hume. Hume argues that if our knowledge of the world is derived from sense experience, then it is not possible to justify general metaphysical principles such as cause and effect, which poses a serious skeptical challenge to empiricist views. Our first protagonist, Thomas Reid, replies that there are basic principles at work in human reasoning and belief formation that account for our knowledge of the world, a view now called common sense Realism. Much subsequent work sought to elucidate these principles of the mind inductively through introspection.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the common sense school butted heads with the idealist approach developed by Immanuel Kant and others in Germany, our other antagonists. Idealism roughly holds that the metaphysical principles in question are built into how we perceive the world. Our story culminates in William Hamilton who combined ideas from Reid and Kant but was ultimately unsuccessful in McCosh’s estimation. He concludes by positing that metaphysics will have to rapidly integrate the results of the natural sciences to remain relevant and combat idealism. This was particularly relevant during a time of rapid scientific advance and the coming wave of idealism in Britain.

While important to establishing the legacy of the Scottish school, I hesitate to recommend this book. The writing is dry in the first third, a bit better in the second, but eventually comes alive in the third. McCosh unfairly handles James Mill to the point of nearly calling him the devil incarnate. Despite being the president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), McCosh barely touches on the Scottish philosophy in America outside of John Witherspoon. Moreover, on McCosh’s telling, everyone including the great skeptic David Hume apparently became a Christian on their death bed.

My copy - the 1966 Georg Olms Verlag printing - has quite the quirk: the font size is inconsistent throughout and can change dramatically between chapters. Roughly, chapter size is proportional to the importance of the subject. Longer chapters on, e.g., Thomas Reid or David Hume have a perfectly nice typesetting. Shorter entries, however, size the font to keep the discussion to just a page or two. In more than one case, this yields extremely small, borderline unreadable text!

Mr. Spencer on Social Evolution

Author: John Elliot Cairnes

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: Google Books

Cairnes argues that Herbert Spencer’s account of social evolution is not empirically verified and is based on a flawed analogy between biological and social evolution. Spencer holds that societies evolve in a manner similar to species, with social structures developing from simple to complex forms, coining the phrase “survival of the fittest” to describe this process. In this view, societies spontaneously evolve new social structures to meet changing conditions, the moral of which is to let nature take its course.

Cairnes charges Spencer with running to consider the consequences of this theory before providing ample (or any) justification. Moreover, Spencer’s positivist social theory does not account the early Medieval period, i.e., the Dark Ages, where civilization declined. Cairnes claims that Spencer provides less historical evidence than the positivist Comte, whom was not held in high regard at the time.

Social evolution as a whole has greater theoretical than empirical challenges. There are major disanalogies between the evolution of societies and the evolution of species. In particular, the evolution of societies is the result of human intentions and actions, while the evolution of species is not. Spencer responds in a short comment claiming that Cairnes has mischaracterized his work and holds his preliminary comments in The Study of Sociology (1873) to too high of a standard.

Can Truths be Apprehended Which Could Not Have Been Discovered?

Author: W. R. Greg

Publication: The Contemporary Review

Link: HathiTrust

Imagine one obtains an idea or proposition in some way like from an apple falling on one’s head. Supposing the proposition is true, Greg asks if we could have discovered the proposition through human faculties and empirical evidence irrespective of its content. For propositions that we can verify, he answers in the positive, since the cognitive tools used to verify the proposition are the same used to arrive at it, i.e., verifiability implies discoverability. His evidence for this is a bit shaky so far, but Greg points out that this explains the futility of attempting to verify religious, spooky, or supernatural propositions using rational or empirical methods. Since these ideas are not discoverable by humans - being outside the scope of our cognitive architecture - they are not verifiable.

This is an interesting short paper, but is it right? Within the scope of mathematical logic, there’s a counterexample with Gödel’s first incompleteness theorem, which says that any theory sufficiently strong enough to model arithmetic contains a true sentence that’s not provable, called a Gödel sentence for the theory. The Gödel sentence is verifiable by its construction; however, it’s not provable from below.

A Recent Work on Cosmic Philosophy

Author: Frederick Pollock

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: HathiTrust

Outlines Of Cosmic Philosophy (1874) is a broad exposition of evolutionary theory from John Fiske applied to social and philosophical quandaries. In this review, Pollock praises much of the book and its attack upon Comte and the positivists; however, he argues that it falls short with respect to metaphysics. Certain metaphysical entities are classed as “the unknowable”, which Pollock takes to be a holdover from Kant’s antinomies. This notion can also be viewed as an optimistic version of von Hartmann’s unconscious. One thing that’s apparent is that both Pollock and Fiske conflate the theories of social evolution from Herbert Spencer with natural selection regarding speciation. This book seems to be seeing how much mileage one can get out of the natural selection argument.

Mathematics

On the Integration of Discontinuous Functions

Author: Henry John Stephen Smith

Publication: Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society

Link: Hathitrust

In the undergraduate calculus sequence, students first encounter integration through the Riemann integral, which calculates the area under a curve of a real-valued bounded function by approximating it with rectangles. In particular, you partition the domain into intervals of length at most $d$ and, for each interval, create a rectangle of width the length of the interval and height a value of the function on the interval. Summing up the areas of the rectangles approximates the area under the curve. If all goes well, as $d \rightarrow 0$, the sum of the areas of the rectangles converges to the desired value.

Riemann showed that continuous functions are integrable and they remain integrable if you allow for a finite number of discontinuities. At the other end of the spectrum, consider the function that takes the value 1 on the rationals and 0 on the irrationals. This function is discontinuous everywhere and not integrable i.e. the rectangle approximation will fail to converge. But how discontinuous can a function be and still be integrable?

In this paper, Smith makes progress toward an answer through a counterexample to a proposed solution from the German mathematician Hermann Hankel in 1870. Hankel proposed that a bounded function is integrable if and only if the set of discontinuities is “scattered”. By this, he meant a topological notion of being small, which we now call nowhere dense. Smith’s counterexample is a function with a scattered set of discontinuities yet is not integrable. The part of his construction that causes issues for integrability is that the set of discontinuities has non-zero “size” in the domain. We call this sort of construction a fat Cantor set.

Smith’s construction foreshadows the development of measure theory in the first decade of the twentieth century, which offered a rigorous notion of “size”. In 1907, Giuseppe Vitali and Henri Lebesgue independently proved that a bounded function is Riemann integrable if and only if the set of discontinuities has measure zero. This differs from Hankel’s result since not all topologically small sets are measure-theoretically small, as evidenced by Smith’s example. These two ways of being small are dual notions that are deeply intertwined.

International Relations

The European Situation

Author: Émile de Laveleye

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: HathiTrust

Following the Franco-Prussian war and the unification of the German Empire, continental Europe found itself in a state of precarious peace. This article updates de Laveleye’s 1873 survey of the relations between European states. de Laveleye thinks that a reasonable observer should expect impending war to result from Germany’s twin chief issues: the Catholic Church and its border with France.

Internally, the unified Germany was divided into a Protestant north and Catholic south. Beyond religious differences among the people, the government sought to stamp out the influence of the Catholic church in state functions, a conflict known as Kulturkampf. To some, the Catholic Church threatened the sovereignty of Germany and could provoke a civil war between the Catholics and Protestants. To complicate matters, the recently annexed Alsace from France is heavily Catholic. de Laveleye views the border between France and Germany, the Rhineland, as an open invitation to further hostilities. France desires to avenge its defeat and reclaim its lost territory. At the same time, Germany may desire expansion; however, it is externally checked by a likely coalition of Catholic states.

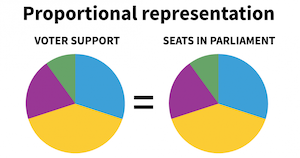

A Note on Representative Government

Author: Thomas Hare

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: Hathitrust

Thomas Hare was a nineteenth century political reformer who sought to solve political problems through the systematic redesign of institutions, particularly with respect to electoral reform. He advocated for a ranked style of proportional voting system, now called single transferable vote, which he believed would give a voice to those with unpopular but important opinions, including both intellectual elites and minorities. In particular, Hare’s scheme would eliminate local constituencies in favor of nationwide voting. As to the disfunction of the current system, Hare points to the case of William Gladstone, who, as a popular prime minister, in the early 1870s, faced several challenges for his seat in Parliament by weaponized local constituencies.

This article responds to Leslie Stephen’s critique of Hare’s proposal from an earlier issue of the Fortnightly Review from the same year. Stephen viewed Hare’s system as an over-engineered and overly complicated piece of “political machinery.” He thought that it placed too much faith in the intricacies of a new voting system to solve fundamental political and social problems stemming from the cognitive limitations of the voting public.

The Liberal Eclipse

Author: John Morley

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: HathiTrust

Following the defeat of the liberals in the 1874 UK general election, the popular former Prime Minister William Gladstone retired from leadership in the Liberal Party, leaving somewhat of a power vacuum at the top. Two possible contenders for leadership in the House of Commons were Lord Hartington and William Edward Forster. Morley argues strongly against the latter who has alienated parts of the Liberal party coalition through various sectarian accommodations to the national education system, which Forster helped push through as legislation in 1870.

Morley offers a cynical view of politics:

There are three sorts of men in the world; first those who earnestly care about social improvement. Second, those who don’t believe in it nor care about it, and boldly say that they do not. Third, those who do not care about it, but pretend that they do. The first are the Radicals; the second are the old Tories; the third are the modern Whigs, whether calling themselves Conservatives or Liberals. Political progress varies with the degree of propulsion which the first sort of men are able to exert upon the third sort.

Without Gladstone, Morley views the Liberals as a rudderless coalition with no identifiable direction. This is an interesting time capsule, since Gladstone would soon return from his hiatus and become Prime Minister again once the Liberals regained power in the 1880 general election.

Philosophy of Science

An Answer to the Arguments of Hume, Lecky, and Others Against Miracles

Author: Alfred Russel Wallace

Link: Google Books

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, scientific consensus increasingly moved toward naturalistic explanations of the world. At the same time, the spiritualism movement was in vogue and built around mediums, seances, and other spooky stuff. In this essay, Wallace argues that the prima facie rejection of “unnatural” explanations is unwarranted by challenging the accounts offered by David Hume and W. E. H. Lecky.

Hume held that it’s never rational to believe in miracles or spiritual happenings since it’s more likely that an observer is mistaken than a law of nature is violated. Wallace contends that Hume’s definition of miracles is so narrow that it excludes the possibility of advancing science by classifying any gap in theory as incredible. While it’s reasonable that testimony on isolated supernatural events is likely in error, some events are well attested such as the powers of mediums during seances at the time.

Lecky argued that the decline of belief in magic and miracles and the increasing secularization of government accompanied the advancement of society. Belief in spiritual events has been a constant since antiquity, and the preference during the past century for naturalistic explanation is an aberration. Wallace suggests one possible explanation for the decline is that the persecution of witches in Europe suppressed the practice of magic until the rise of the spiritualism movement. This perennial account of magic equates the witches of the early modern period with mediums of the day.

Wallace’s arguments for taking spiritualism seriously are ultimately unconvincing. Many tactics employed are reminiscent of those from science skeptics today. An example: we should be open to any alternative account of phenomena, including spooky accounts, since the frontier of science is frequently incorrect and fails to anticipate new findings. This essay is included in Wallace’s On Miracles and Modern Spiritualism: Three Essays (1875).

The First and Last Catastrophe

Author: William Kingdon Clifford

Publication: The Fortnightly Review

Link: HathiTrust

This paper considers how much scientific reasoning can inform speculation about the beginning and end of the world. Specifically, to what extent can we rewind and fast-forward the known physical laws to tell us about the deep past and deep future? Clifford begins with a lengthy informal description of James Clerk Maxwell’s statistical view of mechanics and the physical world as atoms, homogenous in kind, bouncing around in the ether.

Clifford argues that our laws are local in that we can reason about the past and future to some extent; however, our purview of the past is much shorter than the future due to entropy and the arrow of time. More generally, we have no reason to think that the present physical laws are either necessary or hold eternally in our world. Perhaps, our laws hold today but not in the deep past or future. Or that our laws evolved as part of a system and could have been otherwise. These conclusions throw some kinks in simplistic approaches to grand speculations about the universe.

Reply to the Critics of the Belfast Address

Author: John Tyndall

Publication: Popular Science Monthly

Link: WikiSource

John Tyndall’s 1874 keynote address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science was met with intense public backlash and criticism. Tyndall advocated for naturalism and painted a picture of naturalistic science as continually in conflict with religion, much to the detriment of our understanding of the natural world. His critics ranged from dismissing his arguments by attributing them to a sour mood to challenging his domain of discourse. It’s the latter argument that I want to focus on.

from Vanity Fair, 1872

While Tyndall is acknowledged as an expert in physics and the experimental sciences, his critics allege that he overstepped his bounds when speculating about the origins of life and the universe, since these matters are beyond the scope of experimental science. On this view, no results from a lab experiment could ever tell us about the origins of the universe. By advocating for naturalism, Tyndall is wading wholly unprepared into the depths of philosophy and theology.

While Tyndall is largely guilty of this charge, this does not undermine the thrust of his argument. He notes that scientists routinely go beyond the empirical evidence when developing and evaluating scientific theories. Moreover, this sort of inductive reasoning is a reliable guide to understanding the natural world, including its more remote parts. The dispute on this point is really about who gets to claim cosmology and other such areas of inquiry. Should cosmology be informed by our best current theories in physics or should it remain the domain of metaphysical speculation?

Misc

Are Languages Institutions?

Author: William Dwight Whitney

Publication: The Contemporary Review & Popular Science Monthly

Link: WikiSource

Popular Science Monthly

Whitney contrasts two competing perspectives on the study of language: metaphysical and common sense. The former sees language in purposeful terms, as developing toward a particular end, or as an essential property distinguishing humans from other animals. The latter takes language as it exists and asks empirical questions about its nature and function. Metaphysical views on language tend toward sweeping theories and grand narratives and encapsulate the views of leading theorists of the time such as the philologists Max Müller and Friedrich Schlegel. In contrast, Whitney supports the lay view that language is a tool for communication, shaped by practical needs and social interactions. He argues that language evolves organically as a social institution, influenced by cultural and historical contexts rather than by a predetermined purpose or design.

Whitney became involved in an intense feud with Müller over the origin and evolution of language throughout the 1870s. In the latter half of this article, he frames the dispute as his interlocutor uncharitably interpreting his book Language and the Study of Language (1867) while downplaying his admittedly “polemical” language.

Life Insurance

Author: Simon Newcomb

Publication: The International Review

Link: Google Books

Newcomb discusses the economics of mutual life insurance companies. Life insurance is inherently an interesting (and subtly grim) product to price because, unlike fire insurance, not everyone’s house will burn down. The mutual bit means that the company’s beneficiaries are the policyholders rather than investors/stockholders.

the Online Library of Liberty

Newcomb observes that there’s an asymmetry between life insurance contracts and other sorts of financial products: if you miss a payment with life insurance, you “forfeit” all that’s been paid in by no longer being covered. On one view, each payment covers one’s risk of death up through the next payment, and policyholders pay proportional to their risk. On another, the insurance company is more like a savings bank where you make regular deposits and withdraw a fixed amount upon death. Adopting the latter view, Newcomb argues that a policyholder that made regular payments up to some point is owed some compensation when their policy is terminated early, particularly due to non-payment.

He concludes by arguing that insurance could run on a leaner budget if they could get rid of those pesky agents. By the latter half of the nineteenth century, on Newcomb’s view, life insurance had become so ubiquitous - at least among this article’s audience - that agents were no longer necessary to inform the consumer.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee