An Utterly Incomplete Look at Research from 1925

This series looks at research from years past. I survey a handful of books and articles in a particular year from math, economics, philosophy, international relations, and other interesting topics. This project was inspired by my retrospective on Foreign Affairs' first issue from September 1922.

Seven years removed from the armistice, 1925 finds the Western intellectual world grappling with reconstruction, not merely of borders and economies but of the conceptual foundations underlying science and the social order. The selections below reflect this theme of rebuilding. Economists theorize about institutional frameworks and the distinction between productive investment and mere speculation. Philosophers return to perennial questions about universals and common sense with renewed rigor. Statisticians formalize the inferential machinery that would come to dominate empirical research.

Across several pieces runs a persistent question about international order: which arrangements are most beneficial for the future? Many of these books and articles are not merely retrospective analyses but forward-looking proposals: Root arguing that international institutions represent steps toward lasting peace; Flexner articulating a vision for the modern research university; Pirenne theorizing that the large networks of trade increase social complexity and material prosperity. There is a sense throughout of authors clearing ground and laying foundations for what comes next.

I most enjoyed Frank Ramsey’s Universals and the selections from The Atlantic: Speculation and Investment and A Modern University. While I only included two articles from The Atlantic, several were interesting and the magazine was a joy to read this year. A great example is Confessions of an Automobilist, an amusing take on the perils of buying and owning a car in the 1920s. It’s well worth digging through the archives for more!

I ran out of time to cover everything I wanted to this year. Two books in particular are worth mentioning. First is R. A. Fisher’s Statistical Methods for Research Workers, a highly influential practical guide for applied statistics; however, I cover a technical paper formalizing statistical notions from Fisher below. Second is Walter Lippmann’s The Phantom Public, which critiques the notion of an informed public capable of self-governance and offers interesting thoughts on social epistemology. If I’ve missed anything interesting from 1925 that you enjoy, shoot an email my way at brettcmullins(at)gmail.com.

Economics

Speculation and Investment by E. L. Smith

Law and Economics by John R. Commons

Review of The Trend of Economics by Allyn A. Young

Philosophy

Universals by Frank Ramsey

A Defense of Common Sense by G. E. Moore

The Obscurantism of Science by H. G. Townsend

Mathematics

Theory of Statistical Estimation by R. A. Fisher

International Relations

Lenin by Leon Trotsky

Am I a Liberal? by John Maynard Keynes

Steps toward Preserving Peace by Elihu Root

Miscellaneous

Medieval Cities by Henri Pirenne

A Modern University by Abraham Flexner

Economics

Speculation and Investment

Author: Edgar Lawrence Smith

Publication: The Atlantic

Link: The Atlantic Archive

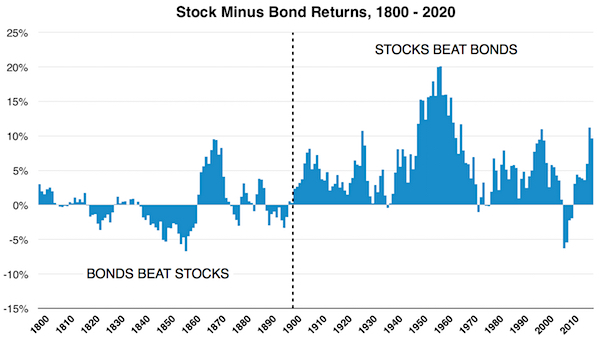

The prevailing wisdom regarding financial markets in the early twentieth century is that bonds were investments for the prudent, while stocks were speculation for the gambler. In his book Common Stocks as Long Term Investments (1924), Smith compares stock and bond performance for various 20-year periods over the past century and finds that diversified equity portfolios almost always outperformed high-grade bonds.

stock portfolios started outperforming bonds

This article attacks the distinction between speculation and investment by viewing various financial instruments as different flavors of the same dessert. Investing in a single stock exposes one to idiosyncratic risk that a firm will fail. This can be mitigated by investing in a basket of diverse stocks, where the idiosyncratic risks average out. Bonds, often thought to be the paragon of safety, are exposed to the risk of rising prices with respect to a given currency. While forwards and futures are viewed with suspicion as speculative instruments, they can be used to reduce one’s overall risk level through hedging.

Smith concludes that an investment should be defined by its ability to protect purchasing power and provide a real return, rather than just the type of security. John Maynard Keynes reviewed Smith’s book favorably in The Nation and Athenaeum. This line of work contributed to fueling the 1920s bull market by legitimizing holding common stock.

Law and Economics

Author: John R. Commons

Publication: Yale Law Journal

Link: JSTOR

Law and economics are often viewed as two related but distinct approaches to thinking about aspects of human behavior. While law codifies tried-and-true practices for contracts and other dealings, economics is seen as an abstract science of efficiency. This narrow view of economics, however, trims the field of most of its content, which is situated within various systems of legal and social rules. Commons argues that both law and economics are in the business of codifying good practices and are intertwined insofar as economic innovations influence the law, while legal innovations shift market dynamics.

This paper is a concise statement of a line of thought in Commons’ Legal Foundations of Capitalism (1924), which makes a case for an institutional approach to economics. On this view, one cannot understand the economy without understanding the legal working rules that define and shape all market activity at a given time. This contrasts markedly with the law and economics approach developed at the University of Chicago in the 1960s. Rather than using the law to understand the economy, Coase, Posner, and friends use economic principles (like efficiency, utility maximization, and price theory) to explain and evaluate legal rules as a system of incentives designed to achieve economic efficiency.

The Trend of Economics, as seen by Some American Economists

Author: Allyn A. Young

Publication: Quarterly Journal of Economics

Link: JSTOR

The Trend of Economics (1924) is a collection of essays from a (mostly) new generation of economists seeking to reorient the field along empirical and institutional grounds and free it from the perceived metaphysical baggage of the past. Young views the overall tone as particularly arrogant and the task as premature in seeking to replace the methods and foundations of economics. He reviews the articles in the volume arranged by the strength of their call for change, which ranges widely from Frank Knight’s contention that economics can only be successful as part-science, part-art to Wesley Mitchell’s burn-it-all-down and rebuild along institutional lines.

business cycles with his 1927 survey

While Young provides insightful commentary, we disagree on several articles. In particular, Young calls William E. Weld’s contribution “unsatisfactory” and not meriting “extended discussion”. However, I found this article refreshing due to Weld’s insistence that causal reasoning ought to become the primary method for the economist as reliable information becomes increasingly available. Young reserves most of his frustration for Wesley Mitchell, whom he regards as having done excellent work on business cycles but threw it all away in favor of Thorstein Veblen’s institutional approach.

Philosophy

Universals

Author: Frank Ramsey

Publication: Mind

Link: JSTOR

This paper takes aim at one of the oldest distinctions in philosophy: that between universals and particulars. This is the distinction between the idea of wisdom and Socrates, i.e., between the property and the thing that satisfies it. On the traditional view, going back to Aristotle and revived by Bertrand Russell, this distinction is fundamental to the structure of reality. Ramsey thinks it spurious, or at least far less fundamental than philosophers have supposed.

Ramsey takes a fresh look at subject-predicate propositions such as “Socrates is wise”. The traditional view takes Socrates as the subject (a particular) and wisdom as the predicate (a universal). The asymmetry seems baked into the grammar. But Ramsey observes that we can just as easily write “Wisdom is a characteristic of Socrates,” reversing the apparent logical roles. If the distinction between universal and particular were genuinely metaphysical, we shouldn’t be able to reverse position of terms without changing the meaning. More precisely, Ramsey argues that atomic facts like Socrates being wise can be analyzed with either term as the subject. The fact itself is symmetric; only our notation introduces asymmetry. Philosophers have mistaken a feature of language for a feature of reality.

The paper concludes that the whole framework of subjects and predicates, particulars and universals, has led philosophers astray. But the upshot is not that we need a better logical notation to capture the true structure of facts. Rather, Ramsey argues that we cannot know the forms of atomic propositions at all. This is a more radical conclusion than it might first appear: it cuts against the central ambition of Russell’s logical atomism, which sought to reveal the hidden structure of reality beneath the misleading surface of ordinary language.

A Defense of Common Sense

Author: G. E. Moore

In the collection Contemporary British Philosophy (2nd Series), edited by J. H. Muirhead

Link: Internet Archive

During the early twentieth century, British philosophy was heavily under the influence of the idealism of F. H. Bradley and J. M. E. McTaggart, though the two would pass away in 1924 and 1925, respectively. These philosophers argued for an understanding of reality where time, space, and individual objects are ultimately unreal or contradictory. In this article, G. E. Moore starts from common-sense propositions that we all (supposedly) know to be true, e.g., asserting “here is a hand” when looking at one’s hand, and uses them to shift the epistemic burden to idealist and other skeptical positions.

Moore’s strategy is to enumerate a series of common-sense propositions that he claims to know with absolute certainty. These include “There exists at present a living human body, which is my body,” “The earth had existed also for many years before my body was born,” and that other human beings have similar experiences and knowledge. From this epistemological foundation, we can infer metaphysical conclusions about the reality of time, space, and other minds.

Crucially, Moore thought that we can fully understand and know the truth of a statement like “here is a hand” in its ordinary sense, even if we cannot explain the complex metaphysical relationship between our sensory experiences and the physical object itself. He charges that skeptics confuse the two, assuming that because we cannot explain the metaphysics of perception, we do not know the object is there.

This article is the most notable essay from the second volume of Contemporary British Philosophy. While I covered the first volume in full last year, the second is largely more of the same, featuring a heavy dose of idealism, which was reflective of the established British philosophers of the time.

The Obscurantism of Science

Author: H. G. Townsend

Publication: The Journal of Philosophy

Link: JSTOR

Writing during the frenzy of the Scopes Trial, H. G. Townsend argues that science operates by producing models that act as a “magic veil” between the human mind and the “terrifying chaos of experience,” reducing the complex world into “static forms and desiccated categories”. While this simplification is necessary for the comforts of modern life, which allows a physician, for instance, to diagnose pneumonia rather than confronting the unique agony of an individual illness, Townsend posits that this practice can become a source of obscurantism when the simplified map is mistaken for the territory.

The crux of the issue lies in the gap between scientific inquiry and its popular assimilation. While scientists (hopefully) recognize the scope and limitations of their methods, popular science may present these findings as absolute mirrors of reality. This disconnect leaves the layman in a no man’s land, reasonably mistaking models for fact. The situation creates false expectations about what science can deliver, eroding trust especially when new ideas challenge established beliefs. Townsend finds that this reckless mode of communication is particularly prevalent with new ideas in sociology and psychology, e.g., IQ, and may push the layman toward reactionary alternatives.

Mathematics

Theory of Statistical Estimation

Author: R. A. Fisher

Publication: Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society

Link: Cambridge Core

Fisher’s 1922 paper On the Mathematical Foundations of Theoretical Statistics argues that statisticians needs precise notions such as consistency, efficiency, and sufficiency, and championed likelihood as the proper basis for statistical inference; however, it left much of the mathematics incomplete. This paper picks up where the former left off by rigorously deriving the sketched results including the information inequality (now known as the Cramér-Rao bound) and establishing the asymptotic optimality of maximum likelihood estimation.

Fisher’s broader program sought to refound statistics on new conceptual ground. The nineteenth century approach, inherited from Laplace and developed by statisticians such as Karl Pearson, relied heavily on inverse probability and Bayesian reasoning. Fisher found this unsatisfying and obscured what he saw as the central problem: extracting information from data. His alternative built everything on the likelihood function, which captured what the data said about parameters without requiring prior beliefs. Sufficiency told you when a statistic captured all the information; efficiency told you how close an estimator came to the theoretical optimum; consistency ensured convergence to the truth.

Fisher also published the book Statistical Methods for Research Workers in 1925, which largely eschewed mathematical rigor in favor of practical guidance. It offered scientists practical recipes for t-tests, contingency tables, and analysis of variance. SMRW was widely read by practitioners and came to be regarded as one of the most influential statistics books of the twentieth century.

International Relations

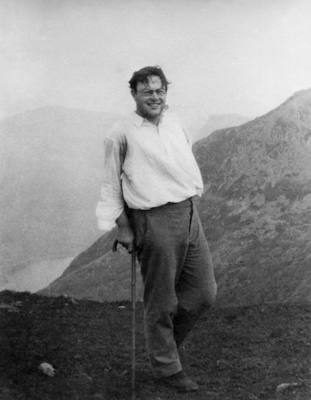

Lenin

Author: Leon Trotsky

Link: Internet Archive

In early 1924, Vladimir Lenin’s illness and subsequent death left the young Soviet Union with a power struggle between Trotsky and Stalin & friends. Both factions sought Lenin’s legacy as a source of legitimation. This book can be seen as part of Trotsky’s campaign to cement his relationship with Lenin and his contributions to the revolution.

The narrative begins in 1902 when Trotsky moves to London to write for the Russian Socialist newspaper Iskra, then managed by Lenin. We’re introduced to this book’s main quirk: characters oscillate between being called by their names and pseudonyms. In one sentence, it will be Vladimir Ilyich; the next it will be Lenin. This convention applies broadly with the activist Vera Zasulich going by three names at one point.

Trotsky sketches a varied picture of Lenin. On the one hand, he recounts an amusing trip to the opera in Paris in which he and Lenin traded shoes. Earlier on, Lenin purchased new leather shoes but found the fit unbearable. Trotsky was initially enthused with the trade but endured a painful walk home afterward. On the other, in political and economic matters, Lenin is cold and calculating, justifying his thinking on longtermist grounds.

We move forward in time in midst of the Civil War in 1918. This part offers the most interesting and substantive discussion in the book over whether or not to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, a peace treaty with the Central Powers withdrawing the Soviet Union from the First World War. Would signing the treaty be abandoning the efforts of laborers elsewhere? To save face, should they wait to sign the treaty until Germany attacks? If so, how much of a sacrifice is reasonable? A whole city? A whole region?

Am I a Liberal?

Author: John Maynard Keynes

Publication: The Nation and Athenaeum

Link: HET Website

The 1924 UK General Election saw a crushing defeat for the Liberal party, who lost 118 of its 158 seats in the House of Commons. This election split the electorate between Labor and Conservatives, a situation that has persisted (mostly) ever since. Foreseeing this, Keynes asks to which of the two parties he should switch his allegiance. On one side, he finds the Conservatives unpalatable whose hard-core is focused on preserving their accumulated power, status, and wealth, even at the expense of new ideas that would benefit everyone. On the other, he calls the hard-core of Labor “the Party of Catastrophe”, who only see the possibility of progress through tearing down existing institutions, even at the expense of new ideas that would benefit everyone.

Keynes sees room for a third party focused on addressing ever-changing economic issues through institutions, which are somewhat insulated from politics. This new Liberal party would need to shed the baggage of its predecessor, which remains mired in nineteenth century policy debates, to focus on economic issues currently facing the voting public, including the increasing role of women in the economy. Rather than forming a new coalition from the ashes of the Liberal party, both left and right parties in the West throughout the twentieth century adopted aspects of Keynes’ technocratic view. This article is prescient today as many Western democracies face similar issues of political polarization and disaffected voters.

Steps toward Preserving Peace

Author: Elihu Root

Publication: Foreign Affairs

Link: JSTOR

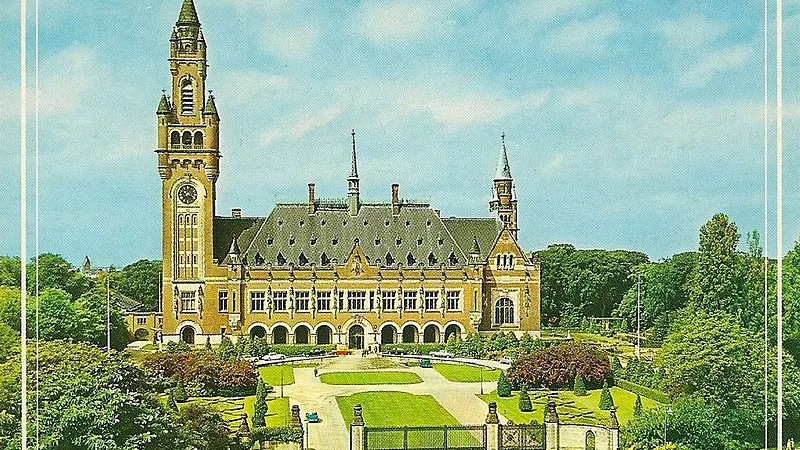

Since the late nineteenth century and given increased impetus by the First World War, diplomats sought a venue for states to arbitrate disputes with the aim of preventing armed conflict. Root, a former US Senator and Secretary of State, posits that the success of such a venue as well as laws and institutions more generally is determined by public opinion. Though public opinion heavily swayed toward ideas of outlawing war, there was no consensus route to accomplish this goal.

in The Hague

Root argues that we should support efforts such as the recently established World Court, even if such an institution isn’t perfect or doesn’t satisfy all of one’s particular asks. Part of the aversion to an arbitration venue as a means to a popular end is simply fear of the unfamiliar. Beginning with a narrow scope, such an institution can prove its worth and expand its scope as needed, legitimating itself over time.

Miscellaneous

Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade

Author: Henri Pirenne

Link: Internet Archive

Pirenne proposes that the shift from Antiquity to the Middle Ages was not caused by the internal decay of Rome or barbarian invasions but by an exogenous shock to trading networks. The Mediterranean functioned as a unified economic system until the Islamic conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries effectively partitioned the sea. The Carolingian era resulted from a land-locked Europe, where the absence of liquidity and long-distance exchange necessitated a retreat into the fragmented, subsistence-based hierarchy of feudalism.

The establishment of trading settlements outside of feudal walls was the locus of change toward a more complex economy. Since merchants required freedom of movement and property rights that feudal law could not support, their growing numbers eventually forced the landed aristocracy to grant charters of freedom. On this view, the medieval city is not an organic outgrowth of the agricultural village, but a distinct institutional innovation driven by the necessities of commerce.

This view that economic connectivity is the primary determinant of societal complexity is known as the Pirenne thesis. Pirenne considers the case of the Varangians (Scandinavians) in the eleventh century, who had a thriving trade network along the Dnieper and Volga rivers, linking the Baltic to Byzantine and Islamic markets. Various conflicts severed these river arteries and catalyzed the area’s regression into a feudal, agrarian state.

This book provides a concrete example of history through the lens of economic forces rather than a political or military narrative. Future work, however, would fail to substantiate Pirenne’s main ideas, particularly with regard to dating the fall in Mediterranean trade with Western Europe.

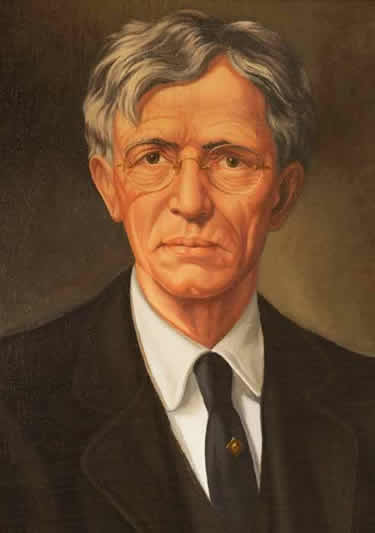

A Modern University

Author: Abraham Flexner

Publication: The Atlantic

Link: The Atlantic Archive

By the 1920s, American higher education looked remarkably like today’s multiversities and is a far cry from the wild west system of the nineteenth century. Publicly funded high schools offered an avenue to a four year college, after which one may continue on to a professional program or a research degree. This article argues that graduate education, particularly research institutions, ought to be unbundled from undergraduate colleges. To produce both knowledge and researchers, graduate study needs to be nimble and exploratory, allowing for quick pivots to new methods and ideas. Undergraduate education, however, is meant to build character and provide structure as much as it facilitates learning in the lecture hall.

Flexner views these goals as antithetical and holds that their commingling hinders both enterprises. He recommends unbundling the research institute. While this sounds drastic, their co-location is more historical contingency than not. Putting his words into action, Flexner cofounded the Institute for Advanced Study in 1930 and managed it for a decade, coinciding with the influx of eminent mathematicians and physicists from Europe including Albert Einstein, Kurt Gödel, and John von Neumann.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee