Top Articles I've Read in 2020

∷

Books: 2025 - 2024 - 2023 - 2022 - 2021 - 2020 - 2019 - 2018

Below are the top articles I’ve read in 2020. This year’s list contains a nice mix of types of articles. A prominent theme in the list is economics and economic methodology with A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas, Economic Modelling as Robustness Analysis, and Thoughts on DSGE Macroeconomics. The Theory of Interstellar Trade is an oddball article from a young Paul Krugman. An introduction to (algorithmic) randomness is an excellent invitation to a technical area of mathematical logic, and Comments on Economic Models, Economics, and Economists is a fun and effective book review on methodology. Finally, there’s four thought provoking articles across political rhetoric, machine learning privacy, social contract theory, and international relations with The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Stealing Machine Learning Models via Prediction APIs, Self-organizing moral systems, The End of Grand Strategy.

The papers below are presented in chronological order.

A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas

Author: Robert A. Mundell

Publication: The American Economic Review

Published: September 1961

Link: Click Here

This article is an introduction to Optimum Currency Areas in both theory and application. The managing of currency through monetary policy by a central bank or other authority serves the purpose of absorbing unemployment through expansion when unemployment is high as well as curbing inflation when inflation is high. This, however, assumes that a region is homogeneous with respect to its need for monetary policy. Some countries may contain multiple regions, e.g., the US had the ailing Rust Belt and the booming Silicon Valley in the 2010s. Other countries may all belong to a single region, e.g., the Nordic countries. In the former case, monetary policy may benefit one region at the expense of another. In the latter case, monetary policy could be coordinated to reduce inefficiencies. The optimum currency scheme divides currencies among homogeneous regions.

The author is careful to note that currencies are not created in a vacuum and are an expression of national sovereignty. It may be the case that a country would accept the inefficiencies to retain control of its currency. However, ideas for economic integration, e.g., the European Union at the time, may prove a testing ground for both an appetite and the application of OCA, and they did!

This article is part of the American Economic Review’s Top 20 articles from the journal’s first 100 years.

The Paranoid Style in American Politics

Author: Richard Hofstader

Publication: Harper’s Magazine

Published: November 1964

Link: Click Here

The Paranoid Style in American Politics is a rhetorical analysis of American politics. The author describes a mode of rhetoric that is often divisive, conspiratorial, and mean-spirited. While the paranoid style is introduced in the context of right-wing thought in the 1960s (the present day of the article), author contends that “The paranoid style is an old and recurrent phenomenon in our public life which has been frequently linked with movements of suspicious discontent…and its targets have ranged from “the international bankers” to Masons, Jesuits, and munitions makers”.

The most interesting bit of the essay discusses examples that employ this style. While one might think that conspiracy theorists have jumbled patterns of thought or crippled epistemologies, the author contends that

“The higher paranoid scholarship is nothing if not coherent—in fact the paranoid mind is far more coherent than the real world. It is nothing if not scholarly in technique. McCarthy’s 96-page pamphlet, McCarthyism, contains no less than 313 footnote references, and Mr. Welch’s incredible assault on Eisenhower, The Politician, has one hundred pages of bibliography and notes. The entire right-wing movement of our time is a parade of experts, study groups, monographs, footnotes, and bibliographies.”

The author closes by conjecturing that this sort of thinking is not unique to a particular time and place; rather, it is part of the human psyche. This essay provides a useful lens when considering the divisive political rhetoric of the present day.

I came across this article while reading Close Companions? Esotericism and Conspiracy Theories from Egil Asprem and Asbjørn Dyrendal which deserves an honorable mention in this year’s list. This paper applies methods from religious studies to better understand conspiratorial thinking and rhetoric.

The Theory of Interstellar Trade

Author: Paul Krugman

Publication: Economic Inquiry

Published: 1978/2010

Link: Click Here

This is an satirical paper written by Paul Krugman in 1978 but not published for over 30 years. As the paper states, it is a serious analysis of a silly topic: the theory of trade across long (light years) distances. The setup is that interplanetary trade can be modeled as international trade; however, interstellar trade requires special considerations: transporting goods will take long periods of time even when traveling near the speed of light; and time becomes relative to the observer (whether on a specific planet or a cargo ship) in an Einsteinian universe.

Krugman “proves” two fundamental theorems of interstellar trade:

(1) “When trade takes place between two planets in a common inertial frame, the interest costs on goods in transit should be calculated using time measured by clocks in the common frame, and not by clocks in the frames of trading spacecraft”

(2) “If sentient beings may hold assets on two planets in the same inertial frame, competition will equalize interest rates on the two planets.”

In addition to being a joy to read, Krugman jabs at the conventions of economic research, pointing to problematic or absurd practices without offering a comprehensive critique. At its worst, this article is the amusing grumblings of a disgruntled researcher; at its best, it’s an interesting take on methodology.

I came across this paper while reading through the Fermat’s Library Journal Club backlog.

Economic Modelling as Robustness Analysis

Authors: Jaakko Kuorikoski, Aki Lehtinen, and Caterina Marchionni

Publication: The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science

Published: August 2010

DOI: 10.1093/bjps/axp049

This article argues that the practice of establishing derivational robustness in economics provides epistemic support for economic theories in lieu of empirical evidence. This attempts to explain what it is that economists do in much of their research.

The authors divide model assumptions into three categories: substantial assumptions, Galilean assumptions, and tractability assumptions. Substantial assumptions “identify a set of causal factors that in interaction make up the causal mechanism about which the modeller endeavours to make important claims”. These are the claims we expect to be veridical. Galilean assumptions act to isolate the causal mechanism modeled by the Substantial assumptions. Tractability assumptions simplify the problem, e.g. assuming some function is linear or simple and so forth.

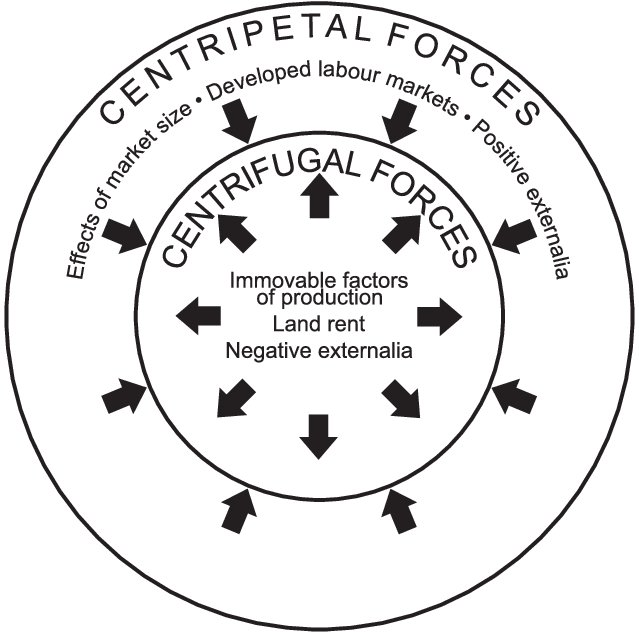

The act of establishing derivational robustness involves proving that the result attained from the Substantial assumptions holds under a variety of Galilean and Tractability assumptions. The authors provide an example from Economic Geography whereby a model is constructed by Paul Krugman showing geographic concentration of firms under particular conditions about transportation costs and other factors. Further research has extended Krugman’s results to show that they hold under more general Galilean and Tractability assumptions. This lends credence that the models’ Substantial core captures the essential mechanisms involved in this economic process.

I discussed this paper as part of my Economic Methodology Meets Interpretable Machine Learning series of posts.

Stealing Machine Learning Models via Prediction APIs

Authors: Florian Tramèr, Fan Zhang, Ari Juels, Michael K. Reiter, and Thomas Ristenpart

Publication: Proceedings of USENIX Security 2016

Published: August 2016

Link: Click Here

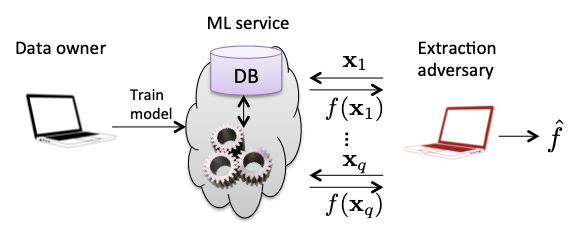

This article introduces the model extraction attack against deployed machine learning models. The goal of this attack is to reconstruct a model given oracle access to the model - a situation that’s common when machine learning models are deployed as a black box behind an API. Often deployment platforms will return more information to users than just the predicted label (in the case of classification) or the predicted value (in the case of regression). In this paper, the authors explore extraction attacks in the setting where confidence scores are additionally returned to the user.

To illustrate these sorts of attacks, consider the case of a binary logistic regression classifier with $n$ features. If confidence scores are provided, an adversary could fully reconstruct the model with $n+1$ (linearly independent) queries by solving a system of equations. The authors provide similar attacks with high (though not perfect) fidelity against multi-class logistic models, decision trees, and some neural networks.

Comments on Economic Models, Economics, and Economists: Remarks on Economics Rules by Dani Rodrik

Author: Ariel Rubinstein

Publication: Journal of Economic Literature

Published: March 2017

DOI: 10.1257/jel.20161408

This is a review of Economics Rules by Dani Rodrik by the economic theorist Ariel Rubenstein. Rubenstein is generally favorable to the book as it is written with non-economists in mind yet contains a substantive discussion of economic methodology. Rodrik argues that economics is a science since it uses models and he adopts a middle position between instrumentalism and realism on the status of models. The book is somewhat critical of economics education arguing for more pluralism.

At one point, Rubinstein goes on a tangent to discuss publishing in economics:

“I commonly ask theorists, both young and old, how many articles they actually read last year in Econometrica, the leading journal in economic theory, excluding those they read as referees. All the answers are either zero or one (with a mode of zero). Reading papers in economic theory has become an ordeal. The substance is lost in a sea of symbols and math.”

“Most disturbing is the unbearable length of papers. Card and Della Vigna (2013) noted that the average paper in the top-five journals almost tripled in length between 1970 and 2012. I (still) don’t believe that there is a paper in economic theory that requires more than fifteen pages, including proofs and references.”

Economics Rules is compared and contrasted throughout to Rubenstein’s book on economic methodology Economic Fables. This is a great review and makes me want to read both books in the future!

At the least, you should check out Rubinstein’s worldwide directory of coffeeshops.

Self-organizing moral systems: Beyond social contract theory

Author: Gerald Gaus

Publication: Politics, Philosophy, and Economics

Published: August 2017

This article introduces and explores the ethical diversity view of justice (sometimes called New Diversity Theory) which views justice as the dynamics of heterogenous moral agents. This is in contrast to views of justice where one argues that such and such is the preferred concept of justice, much like how traditional moral philosophy argues for a particular moral theory, e.g. deontology, as the preferred moral theory. We can see an example of this latter case in John Rawls’ social contract theory of Justice as Fairness where it is assumed that agents share homogenous beliefs behind the veil of ignorance.

With this backdrop, Gaus explores this view of justice through agent-based models where agents have utility judgments with respect to two moral rules and differentially value how others conform to their preferred rule. I wouldn’t put too much stock into these initial results; however, this paper helps to formulate the agenda for future research.

Jerry Gaus passed away unexpectedly in August 2020. His final book The Open Society and Its Complexities is to be published by Oxford University Press in 2021.

An introduction to (algorithmic) randomness

Author: Rutger Kuyper

Publication: Nieuw Archief voor Wiskunde

Published: March 2018

Link: Click Here

This article is an excellent short introduction to algorithmic randomness (not randomized algorithms!) that provides both intuition for the notions of randomness along with the clarity of precise mathematical definitions. This is the level of clarity and rigor that introductions and invitations in mathematics should strive for.

The author navigates through several candidate definitions of randomness using the mental model of infinite sequences of coin tosses as points in the Cantor space. On this journey, we move from all such sequences to consider only computable sequences - sequences that can be constructed by an algorithm. Finally, we arrive at the generally accepted concept of algorithmic randomness, Martin-Löf randomness, and discuss its three popular equivalent formulations.

If you’re looking for a more gentle treatment or just something odd, check out this profile on algorithmic randomness in Vice Magazine.

Thoughts on DSGE Macroeconomics: Matching the Moment, But Missing the Point?

Author: Anton Korinek

An Essay in Toward a Just Society: Joseph Stiglitz and Twenty-First Century Economics

Published: August 2018

Link: Click Here

This paper discusses the costs and benefits of the dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) approach to macroeconomics, the current dominant methodology over the past few decades. The salient characteristics of these models are that they are dynamic optimizations, i.e. over an infinite time horizon, include stochastic shocks to represent uncertainties, and constitute an equilibrium analysis (often general equilibrium) that has microfoundations, i.e. the macro-level concepts can be reduced to micro-level phenomena. Korinek focuses heavily on the latter of these.

One advantage microfoundations offer is welfare comparisons between alternative policy proposals. Though these are predicated on the macroeconomic model being correctly specified. DSGE models seem to be caught in an awkward place between prediction and inference much like many econometric models. For instance, when DSGE models are specified, one will often constrain the model so that some moments of random variables match the values observed empirically. Obviously, some moments will be left out, particularly higher moments that may deal with tail events.

The author argues that building macroeconomic models is increasingly becoming an engineering task where the innovations are in technical details of dynamical systems or dynamic optimization rather than conceptual insights into the macroeconomy. For instance, some macro-level phenomena may be emergent and not reducible to the micro-level which is not an uncommon theoretical phenomenon. The author offers an amusing thought experiment here:

“To put it more starkly, we know that physicists understand the micro-level processes that occur in our bodies in much greater detail and precision than medical doctors – but would you rather see your physician or your physicist if you fall sick, on the basis that the latter better understands the micro-foundations of what is going on in your body?”

The End of Grand Strategy: America Must Think Small

Authors: Daniel W. Drezner, Ronald R. Krebs, and Randall Schweller

Publication: Foreign Affairs

Published: May/June 2020

Link: Click Here

This article argues that the era of grand strategy in international relations is over. Grand strategy is the notion of a coherent direction to guide the decisions of a state. The authors argue that having a grand strategy, such as containment during the Cold War years or liberal internationalism until recently, is not feasible given the current divided and unstable state of US politics. These divisions are such that the country lacks a national identity, expertise in foreign policy (and in general) is questioned, and political polarization urges new administrations to try to erase the decisions of the prior administration.

“Grand strategy is dead. The radical uncertainty of nonpolar global politics makes it less useful, even dangerous. Even if it were helpful in organizing the United States’ response to global challenges today, an increasingly divided domestic policy has made it harder to implement a coherent and consistent grand strategy. Popular distrust of expertise has corroded sensible debate of historical lessons and prospective strategies. Populism has eviscerated the institutional checks and balances that keep strategy from swinging wildly.”

The authors suggest that the way forward amid this uncertainty is by adopting the principles of decentralization and incrementalism. The former refers to pulling unilateral power away from the executive branch; the latter to making smaller changes that will not result in enormous changes in policy every four years or so. I found this article particularly interesting as it shifts back and forth between the practice, theory, and metatheory of international relations.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee