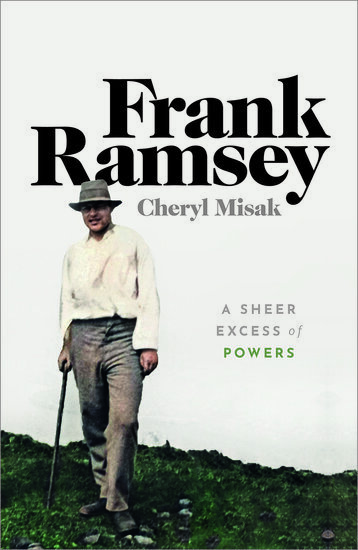

A Review of Frank Ramsey, A Sheer Excess of Powers by Cheryl Misak

Frank Ramsey (1903-1930) was a Cambridge philosopher who made significant contributions to a variety of areas on the outer boundaries of philosophy. To name a few well-known ideas to which he contributed: Ramsey theory in combinatorics, subjective probability, and intergenerational welfare economics.

My interest in Ramsey stems from the sheer variety in the ideas he originated and developed especially since they largely coincide with my interests. I first heard of Ramsey as an aside in an undergraduate seminar on logical positivism but only took away that he had something to do with Wittgenstein. I encountered him again soon afterward while reading commentary on J. M. Keynes’ A Treatise on Probability. I became curious about what was going on in interwar Cambridge where an economist writes a book on the foundations of probability and then is critiqued by a mathematical philosopher who goes on to develop a massively influential account of probability and decision making himself. After listening to the well-known BBC Radio program on Ramsey’s life, I was hooked but didn’t go much deeper than reading a handful of essays from The Foundations of Mathematics and other Logical Essays, a collection of drafts and notes published just after Ramsey’s death and edited by Richard Braithwaite. Little did I know that all this paints an incomplete picture of Ramsey’s thought.

This brings us to Cheryl Misak’s book which is a comprehensive biography of Ramsey’s short but eventful life. It is divided into three parts roughly corresponding to early life, undergraduate studies, and professional career. Below is a brief look at each part.

part one

These chapters cover Ramsey’s family history and origin story up through his graduation from Winchester College, a selective boarding school in England. The author paints a vivid picture of the harsh conditions and (now odd) strictures of English boarding school life. One instance in particular had living quarters so cold that the children were able to keep snowmen indoors. During this time, the first World War broke out which the author uses to frame the political persuasions and nationalist fervor of the time.

part two

In part two, Ramsey is an undergraduate in mathematics at Trinity College struggling with his personal and romantic life, refining his political positions, and following his many interests. During this time, Ramsey becomes involved with various clubs and societies - some quite exclusive such as the Apostles - is introduced to the Bloomsbury Group, and seeks out psychoanalysis in Vienna to cure his anxieties. It’s also during this time that Ramsey worked with Wittgenstein on translating the Tractatus into English producing what’s known as the Ogden translation.

Alongside Ramsey’s story is an exploration of the backdrop of 1920s Cambridge in midst of change. The colleges and Tripos exams were being reorganized, the PhD was established as the path to professorship, and women could increasingly attain education at Cambridge through Newnham and Girton colleges (though not as full students until the late 1940s). Among the young intelligentsia, psychoanalysis was the topic du jour (a bit like cryptocurrencies today!). Though some topics are relegated to passing comments, the author helps transform this intellectual hotbed from an alien world to something more familiar.

part three

The third part is where this book excels (or at least grabs my interest). It focuses on Ramsey’s intellectual life once he obtained a university position in King’s College. The author (given her pragmatist leanings) focuses on Ramsey’s gradual adoption of a sort of Peircean pragmatism and how pragmatist elements are found increasingly throughout Ramsey’s work. For instance, in Truth and Probability, belief through actions (or hypothetical actions as betting odds) rather than something along the lines of the rationalist/logical probability of Keynes form the basis for Ramsey’s subjective probability.

It was during this time that Ramsay made his contributions mentioned in the introduction. Ramsey Theory came out of a paper in mathematical logic called On a Problem of Formal Logic that considered the decidability of a particular set of formal languages - an area that would later develop into computability theory. Collaborating with Keynes, Piero Sraffa, and especially Arthur Pigou, Ramsey produced interesting neoclassical analyses of intertemporal saving and taxation.

In the last year of Ramsey’s life, Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge and absorbed much of Ramsey’s time with his demanding personality. Ramsey pushed back against logical positivism and the picture theory of the Tractatus and advanced pragmatist-flavored positions. The two also discussed mathematics and logic - intuitionism in particular - and Ramsey even served as Wittgenstein’s PhD advisor.

Though he was spending much time outside of philosophy proper, Ramsey was also working on a book developing a pragmatist account of truth when he died, potentially as an extension of Truth and Probability. Though sections of his notes were published in a heavily edited form soon after his death by Richard Braithwaite, the notes from this book as well as notes on intuitionism in mathematics were not published in full until 1991.

reflections

Much like with my commentary on Exact Thinking in Demented Times, the author focuses a great deal of time (especially in parts one & two) on Ramsey’s personal life, especially his love life and associated anxieties. While a biography is surely not complete without some such detail, this focus potentially crowds out other topics.

As with any figure that dies young, the question of what they would have done and what would be their effect on such-and-such fields had they lived looms ever present. While it’s fun to speculate on whether or not Ramsey would have worked with Turing at King’s, collaborated with Wittgenstein on the philosophy of mathematics, and continued to develop pragmatist positions, it’s not clear where the line is between a helpful exercise and speculative fiction. The author handles this well by addressing but not dwelling on the questions.

Going into this book, my understanding of Ramsey was largely consistent with the “popular conception” which viewed him as an analytic philosopher who made numerous contributions to a variety of areas; however, this does not capture the pragmatic turn that Ramsey undertook during the last few years of his life, especially evident when Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge. The notes detailing the pragmatist positions Ramsey was developing were only published relatively recently (or at least well after the BBC Radio program). It was a pleasure to learn about how Ramsey sought to carve out his own positions and break away from the currents of the early Analytic philosophy of Wittgenstein, Russell, and the Vienna Circle.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee