Interesting Books I've Read in 2024

∷

Books: 2025 - 2024 - 2023 - 2022 - 2021 - 2020 - 2019 - 2018

Below are some interesting books I’ve read in 2024. The bulk of what I’ve been reading is either wrapped up in my research on differential privacy or for my project looking back at research from 100, 150, and 200 years ago. Two of the four recommendations below are from the latter project, but all four are of interest from an historical perspective. Wisdom’s Workshop is a history of the American research university from Medieval times to the present. William Stanley Jevons’ The Principles of Science is a wide-ranging treatment of logic and philosophy of science from 1874 that’s bursting with ideas - some more developed than others. Ballyhoo! is a history of professional wrestling and combat sports from its outlaw roots in the late nineteenth century through the first half of the twentieth century. Finally, John Ramsay McCulloch’s Discourse on Political Economy from 1824 is the first history of economic thought from the era of the classical economists.

Whenever I preorder a book or get it fresh from the press - which isn’t very often - I tend to have a strong reaction. In the case of Jerry Gaus’ posthumous The Open Society & Its Complexities from 2021, I loved how he combined a variety of evidence from anthropology and evolutionary theory with his work on strategic accounts of moral diversity.

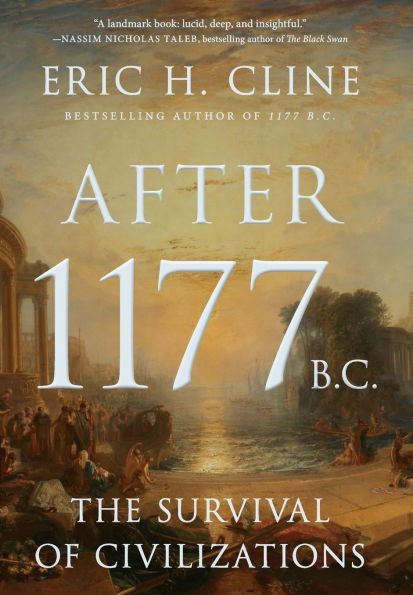

After stumbling across Eric Cline’s 1177 B.C. in a bookstore a few years ago and loving it, I eagerly awaited the coming sequel. Once After 1177 B.C. arrived in April of this year, I was left a bit disappointed. This book delivers in terms of continuing the narrative and revisiting old friends; however, Cline’s analysis is much less convincing this time around. He seeks to explain why, following the Late Bronze Age collapse, some civilizations eventually gained in power such as the Assyrians and Cypriots, some floundered such as the Egyptians, and others virtually disappeared such as the Hittites and Mycenaean Greeks. The proposed explanation is social resilience or adaptability, which boils down to redundancy in power structures, personnel, and social bonds. From this, Cline attempts to draw lessons for the world today, which comes off as more dubious than not.

If you have some thoughts on my list or would like to share yours, send me an email at brettcmullins(at)gmail.com. Enjoy the list!

Wisdom’s Workshop: The Rise of the Modern University

Author: James Axtell

Published: 2016

Wisdom’s Workshop traces the history of the American research university from the Medieval universities of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries to the sprawling multiversities of today. The narrative begins with a look at Medieval colleges. Of particular note are the horrid conditions of libraries. Before the advent of the printing press, accessing manuscripts was rather difficult for the average scholar. Not only were library hours limited by the available sunlight but the books were frequently chained to the shelves!

of Leiden by J. C. Woudanus (1610)

Early American universities such as Harvard College imported their structure from Oxford and Cambridge and were created to produce clergy and administrators for the colonies. These schools were small, only maintained a few faculty, and were largely clustered in New England.

The nineteenth century saw the proliferation of schools across the US but within a chaotic and unorganized system. These were largely secondary schools and liberal arts colleges. Graduate study in the modern sense was not present in the early nineteenth century outside of professional studies.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, students desiring research training in state of the art methods and thought studied at German (or nearby) universities. Looking at research in the US and UK at the time, we can clearly see the influence of this arrangement through an interest in both German thought and the virtues of their research-focused system of higher education. By the close of the nineteenth century, however, this system had been imported and adapted to form US graduate programs.

Axtell views the golden age of the research university as roughly from the gilded age to the Second World War. The university consisting of liberal arts undergraduate study and research-focused graduate study was fully formed; however, the universities retained many differences as to what material is taught, how it is delivered, and so on. The funding that flowed into universities during the response to the Great Depression and the war effort was a homogenizing force that standardized curricula and student expectations.

I anticipated a gloomy prediction of the future (along the lines of Brad DeLong’s Slouching Towards Utopia). Axtell, instead, suggests that the university will adapt and survive as it as done in the past. I strongly suggest this book for anyone getting a PhD or in academia more generally to better understand the context of the institution at which they work and study.

The principles of science: a treatise on logic and scientific method

Author: William Stanley Jevons

Published: 1874

Link: Internet Archive

A prominent debate in nineteenth century philosophy of science concerned the role of deduction in scientific reasoning. William Whewell proposed that scientific inference consists of induction to form general laws and deduction to apply or test these laws in particular cases. John Stuart Mill, on the other hand, argued that scientific inference is purely inductive and empirical.

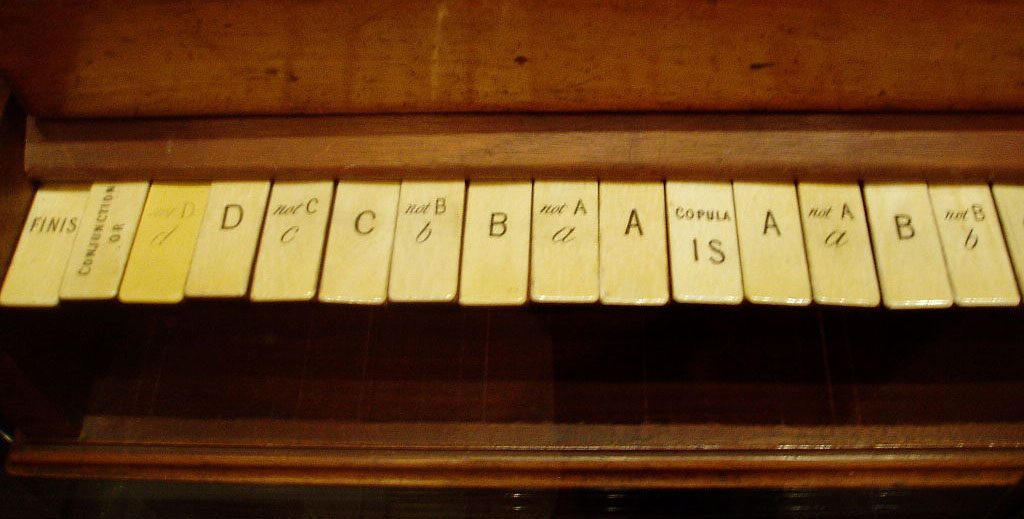

This book develops a wide-ranging account of scientific reasoning, in line with Whewell and unified by what Jevons’ calls the Law of Identity. While the notion of logical identity seems vacuous, it serves as the bedrock for Jevons’ analysis of various topics: logic, arithmetic, probability, induction, and the philosophy of science.

Jevons begins with an odd account of predicate logic, where formulas are constructed from the conjunction of predicates. We can think of a conjunction of predicates as the intersection of the extension of each predicate i.e. the subset of the domain that satisfies all predicates in the conjunction. He introduces operators such as or to join conjunctions into formulas. The accompanying unwieldy system of deduction is equivalent to reasoning about the extension of the formulas, though with a limited set of inference rules. At one point, the existential quantifier is even expressed as a predicate.

Jevons treats induction as the inverse of deduction. He draws an analogy to calculus, arguing that deductive inference, like calculating derivatives, is a more straightforward process than inductive inference, resembling integration. Given that induction with certainty is too epistemologically demanding, he argues that general laws, such as those in natural science, can only be established probabilistically.

from the Online Library of Liberty

Jevons gets a lot of milage out of the Law of Identity. In probability, it pops up as the principle of indifference, which says that all possible outcomes should be considered equally likely absent evidence favoring any outcome. This implies an epistemic interpretation of probability, where probabilities represent uncertainty or ignorance.

There’s so much going on in this book that my treatment above just scratches the surface. Jevons’ approach is idiosyncratic but interesting and bursting with ideas. With that being said, I find it difficult to recommend this book in general. I’m surprised, though, that I had never heard of this book before digging it up while planning my look back at 1874.

Ballyhoo!: The Roughhousers, Con Artists, and Wildmen Who Invented Professional Wrestling

Author: Jon Langmead

Published: 2024

From the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth, professional sports grew from a bed of chaos into the organized leagues we know and love today. Jon Langmead’s Ballyhoo! tells the story of professional wrestling’s role in this transformation through a series of vignettes built around promoter Jack Curley. In many ways, Curley exemplifies the American dream. He was born to an immigrant family in San Francisco, made his way to Chicago for the World’s Fair, stumbled into the shady world of combat sports promotion, and through several ups and downs rose to the top of his industry. By the end of his life, Curley would rub shoulders with high society in New York and beyond and be mentioned alongside contemporary sports icons Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey.

Along the way, pro wrestling evolved from outlaw fights and circus shows to sold-out events at Madison Square Garden. Wrestling has an alluring appeal that sets it apart from boxing and team sports: the possibility of a good show every time.

With thousands yelling and stamping their feet, mesmerized by the action in the ring, it represented the unusual alchemy of professional wrestling in its purest form: a bell, a referee, and two grown men dressed in their underwear, starkly lit, captivating a crowd by simulating athletic competition.

Langmead uses sports journalists from the time as a second voice in his narration. As we get to know them, they play the dual role of character and storyteller. Unlike an out-of-time narrator, these journalists capture the raw excitement of the events and engage in inside-baseball intrigue. From a New Yorker article Cauliflower and Pachyderms from 1934, journalist Alva Johnston speculates on audience psychology:

There is a common belief that wrestling matches are fixed…This adds greatly to the interest and partly accounts for the popularity of the sport. Betting men enjoy the added element of uncertainty; cynics appreciate the ugly rumors…The subject of fixing is always interesting; the question is not only whether a match has been fixed but whether it has been fixed securely, and whether somebody may not come along at the last minute and fix it the other way. Then, too, running like an unknown X through all calculation is the possibility that the thing maybe on the level.

The ambiguity of legitimacy and recurrent scandals is partly what makes the history of professional wrestling interesting. From the promoter’s perspective, to maintain popularity it’s best for the paying fan to focus on future cards and not to remember when the last big main event was either a bust or screwy. The long-term outcome of this strategy, however, is that much of the past gets forgotten. Langmead’s contribution is to dig up that past through extensive archival research and weave a gripping story.

A Discourse on the Rise, Progress, Peculiar Objects and Importance of Political Economy

Author: John Ramsay McCulloch

Published: 1824

Link: Google Books

This short book is regarded as the first history of economic thought from a classical economist but is as much an argument for the field of political economy itself. McCulloch presents economics as approximating a completed science and spends much of the book sketching its development. He begins with the mercantilists who thought about the right issues in the wrong way by, among other issues, advocating for restrictive trade policies. Dudley North is credited with turning the tide toward liberal thinking in the late seventeenth century.

from the Online Library of Liberty

François Quesnay and the Physiocrats were the first to systemize economics as a science of wealth i.e. think in terms of general laws. With The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith offered the first comprehensive treatment of economics. McCulloch argues that Smith’s work was a great leap forward but that it was still incomplete. He credits David Ricardo with filling in most of the gaps such as with the labor theory of value. This chronology is not substantially different than other texts such as Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers from 1953.

Though often confounded with political theory, McCulloch argues that political economy is a distinct field. He defines it as the science of wealth and the laws governing its production, distribution, and consumption. Political economy is indispensable to the legislator from taxation and regulation to trade between states. Doing otherwise is essentially being willfully ignorant.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee