Interesting Articles I've Read in 2022

∷

Books: 2025 - 2024 - 2023 - 2022 - 2021 - 2020 - 2019 - 2018

Below is a collection of interesting articles I’ve read in 2022. There are two papers in differential privacy: A Better Privacy Analysis of the Exponential Mechanism and Differentially Private Approximate Quantiles. There’s an article in the history of mathematical philosophy and a survey introduction to an area of logic: The introduction of topology into analytic philosophy and Incomplete and Utter Introduction to Modal Logic. Two papers border on the practical side of the philosophy of science: Stylized Facts in the Social Sciences for social science research and Does Academic Research Destroy Stock Return Predictability? for finance.The World Putin Wants discusses Russia’s rhetoric from the war in Ukraine. To round out the collection, we explore the influence of a wayward early 20th century archaeologist, build a simple mathematical model of tennis, ponder whether NLP models have intentional states, and consider the role of private property among early humans.

Stylized Facts in the Social Sciences

Author: Daniel Hirschman

Publication: Sociological Science

Published: 2016

Link: Click here

Stylized facts are “empirical regularities in search of theoretical, causal explanations.” Hirschman presents a model of social science research where empirical researchers produce stylized facts that then become the data to which theoreticians model, thereby filling the role of phenomena and crucial experiments in the natural or experimental sciences. Some prominent examples of stylized facts include

“Democracies rarely go to war with each other”;

“The share of income going to the top 1 percent in the United States doubled since 1980”;

“Nations with debt-to-GDP ratios in excess of 90 percent experience lower GDP growth.”

Hirschman identifies four fundamental properties of stylized facts: they make ontological claims about the social world; they are often presented both in technical and lay terms; they frequently posit non-robust or associational relationships; and they serve as normative claims on how best to summarize the findings of a data analysis or to contribute to such-and-such debate. As the above examples illustrate, stylized facts need not be true (or general) and are often used (and abused) in policy debates.

In my view, this an exemplary philosophy of science paper which sheds light on actual scientific practice. In particular, this paper caused me to reflect my work on measuring income mobility. For instance, one way to frame the analysis in Earnings Mobility and the Great Recession is that we proffer the stylized fact that “among low-wage workers, earnings mobility increased following the Great Recession” and our follow-up analysis attempts to explain this finding.

The World Putin Wants: How Distortions About the Past Feed Delusions About the Future

Authors: Fiona Hill and Angela Stent

Publication: Foreign Affairs

Published: 2022

Link: Click here

In July 2021, Vladimir Putin published an essay presenting a suspect history of Russian relations with Ukraine as well as questioning Ukrainian sovereignty, which some analysts took as a pretext for an invasion. Such an invasion came in February 2022 and is ongoing at the time of writing. This article analyzes Russia’s rhetoric and strategy in the context of Putin’s essay and his other writings and speeches. The thrust of the argument is that “Putin seeks to build his version of a Russian empire.”

While I’ve seen several interesting articles on Ukraine, including much great reporting, I found that Hill and Stent’s article best explains the rhetorical grounds for the invasion. Here is a conversation between the authors from the Brookings Institute. Two other articles in a similar vein are Timothy Snyder’s Ukraine Holds the Future in Foreign Affairs and Russia’s Pseudo-Intellectuals in Francis Fukuyama’s American Purpose.

This article appeared in the centennial issue of Foreign Affairs. Earlier this year, I looked back at the magazine’s first issue from Fall 1922.

A Better Privacy Analysis of the Exponential Mechanism

Authors: Ryan Rogers and Thomas Steinke

Publication: DifferentialPrivacy.org

Published: 2021

Link: Click here

Private selection is a fundamental task in differential privacy where, given a collection of options and a score for each option calculated on a dataset, one chooses the approximately best option while limiting disclosure risk for records in the dataset.

This blog post summarizes recent research on the Exponential mechanism - the most common algorithm for private selection - and conversions between DP variants. A common workflow for designing complex differentially private algorithms is to first prove that the simple component algorithms satisfy a common DP variant with nice properties for one’s application such as Concentrated Differential Privacy, then convert the combined algorithm to a more interpretable and prevalent DP notion such as Approximate Differential Privacy.

The primary result discussed is an efficient conversion of Exponential mechanism to Concentrated Differential Privacy that improves on the best known result by a factor of 4. This is significant, since it allows for more accurate results while providing the same privacy guarantee. This result is used in my recent work designing differentially private synthetic data algorithms.

The introduction of topology into analytic philosophy: two movements and a coda

Authors: Samuel C. Fletcher and Nathan Lackey

Publication: Synthese

Published: 2022

Link: Click here

During the 20th century two distinct conceptions of topology found their way into philosophical discourse: geometric and algebraic.

The geometric conception is largely concerned with defining notions of points, events, and basic observations in space-time given the backdrop of relativity theory and logical atomism. The authors contend that the geometric conception entered into philosophy as a reaction to Einstein’s theory rising to prominence following the 1919 Eddington experiments. For instance, in the early 20th century, both Bertrand Russell and Rudolf Carnap were working on empiricism and the foundations of physics but only employed topological reasoning following the widespread adoption of general relativity. Later, the geometric conception of topology found additional application in mereology, providing a useful language to express formal ontologies.

The algebraic conception employs the correspondence between topology and logic stemming from results such as Stone’s representation theorem. One thread of this conception studies topological semantics for logics such as modal and intuitionistic logics. A second thread is topological learning theory which studies the learnability of hypotheses where the difficulty (or simplicity) of learning a hypothesis corresponds to the topological complexity of the hypothesis over the space of possible observation histories.

A Geometric Series from Tennis

Author: Michael K. Kinyon

Publication: The College Mathematics Journal

Published: 2005

Link: Click here

This is a short, fun article exploring the probability of winning a game in tennis if the probability $p$ of winning a point is known. After a bit of reflection and combinatorics, this probability can be represented as a geometric series to account for indefinite deuce/advantage point pairs. Solving for this probability is an excellent application of geometric series to everyday life.

The author takes the analysis an additional step by observing that this probability is non-linear and symmetric about $0.5$ as a function of $p$. Since $0.5$ is an inflection point, the gains in the probability of winning a game are much higher when improving against an evenly matched opponent than against a much better or much worse opponent.

In reading this, I am reminded of Pick the Largest Number, both of which were featured in Fermat’s Library Journal Club.

Does Academic Research Destroy Stock Return Predictability?

Authors: R. David McLean and Jeffrey Pointiff

Publication: The Journal of Finance

Published: 2016

Link: Click here

This paper estimates the effect of publishing investing strategies in academic papers on the performance of those strategies. The authors limit the study to long-short equity strategies that only use publicly available cross-sectional data i.e. observe prices at time $t$ to predict prices at time $t+1$. Data is gathered by reimplementing nearly one hundred proposed strategies and generating performance of the strategy within the initial sample period (in-sample), out of sample but prior to publication (out-sample), and post-publication. Note though that not all strategies could be implemented as originally described due to vagaries, changes to publicly available data, etc.

The idea is that the in-sample performance can be decomposed into generalization error (the paper calls this statistical bias), post-publication performance, and the effect of other traders using the same strategy post publication.

“We estimate the effect of statistical bias to be about 26%. This is an upper bound, because some investors could learn about a predictor while the study is still a working paper. The average predictor’s return declines by 58% post-publication. We attribute this post-publication effect both to statistical biases and to the price impact of sophisticated traders. Combining this finding with an estimated statistical bias of 26% implies a publication effect of 32%.”

An excellent complement to this paper is An Engine, Not a Camera. Also, the authors should be commended for the tremendous amount of work that must have went into this paper.

Witches and Aliens: How an Archaeologist Inspired Two New Religious Movements

Author: Jeb J. Card

Publication: Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions

Published: 2019

Link: Click here

The late-19th/early-20th century archaeologist Margaret Murray greatly influenced both fringe religious movements and science fiction. Murry was a prominent Egyptologist at University College London and was key in training a generation of Egyptologists.

Beginning with The Witch-Cult in Western Europe in 1921, Murry turned her attention to developing and popularizing the idea that “historical and folkloric accounts of witches are memories of an ancient persecuted religion, the Old Religion, dating back to the Pleistocene period.” The so-called “Witch-Cult hypothesis” had antecedents such as with the statistician Karl Pearson; however, its cultural influence greatly grew with Murry. Unfortunately, much of Murry’s evidence consists of a tortured interpretation of the witch trials in Europe in the late Middle Ages with a dash of alternative archaeology.

Murry’s later writing claimed that secret Old Religion cults were still in practice which directly influenced the founding of Gardnerian Wicca. This, in turn, lead to the spread of Wicca groups and the Neo-pagan movement which is still alive today.

A second thread of influence came through the science fiction writer H.P. Lovecraft whose writing incorporated themes of secret cults and such following reading Murry in 1923. Lovecraft explicitly mentions Murry’s “Witch-Cult” in both The Horror at Red Hook and The Call of Cthulhu.

Talking About Large Language Models

Authors: Murray Shanahan

Published: 2022

Link: Click here

Fall 2022 saw an increase in public interest in the latest round of generative NLP models often called large language models (LLMs). This timely article argues that researchers and practitioners ought to be cautious when assigning intentional states such as knowledge and belief to LLMs. Shanahan’s observation is not novel but is worth considering: while LLMs can have really impressive performance for some tasks, they “simply generate sequences of words that are statistically likely follow-ons from a given prompt.” So LLMs don’t reason like humans and, therefore, cannot be ascribed intentional states.

Assigning intentional states as shorthand is a common practice across many fields. For instance, ask any logician to read “$\mathcal{M} \models \varphi$” and they’ll likely say “$\mathcal{M}$ thinks $\varphi$”. Yet I venture that not many think that a model of arithmetic actually thinks. Matters are more tricky for NLP models and systems, since they are meant to mimic a human mode of communication. The difficulties with anthropomorphizing models can vary by domain as well. For instance, it seems much more reasonable to say that a bounding-box computer vision model “looks” than that ChatGPT “thinks”.

Incomplete and Utter Introduction to Modal Logic

Author: Danya Rogozin

Published: 2019/2020

Link: Click here

A modal logic is a formal system modeling deduction for modal expressions i.e. expressions that include truth value qualifiers. For instance, in standard propositional logic, sentences are formed by combining propositional variables $P, Q, R, \ldots$ with operators $\lor, \land, \neg, \rightarrow$ representing or, and, negation, and the material conditional. A modal propositional logic adds additional operators representing truth qualifiers such as “it is necessary that…”, “it is possible that…”, “it will be the case that…”, “it is permissible that…”, and so on.

Rogozin’s article is an ambitious introduction to modal propositional logic in two parts. After a brief history and mathematical background, the first part develops the syntax and typical semantics (Kripke semantics) for propositional modal logics. Whereas the first part surveys basic ideas in modal logic, the sequel dives into applications. The one I find most interesting is an alternative semantics (topological semantics) which interprets formulas in a modal logic in terms of the open and closed sets of a topological space. Moreover, imposing various structure on topological spaces corresponds to changing the expressivity of the logic. An open area of research involves identifying which structural properties correspond to which modal logics. See this paper for an example.

The prospective reader should note that the article contains quite a few typos and formatting errors. While it is rough around the edges, it reads as a labor of love that’s well informed and bursting with enthusiasm.

Primitive Communism: The idea of primitive communism is as seductive as it is wrong

Author: Manvir Singh

Publication: Aeon

Published: 2022

Link: Click here

This article argues against primitive communism: that early human tribes didn’t have private property. This view can be found in many classical economists in some form and is most closely associated with Karl Marx from his posthumous The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Singh describes Marx’s book as an early entry in big history. Much field work in anthropology demonstrates that there’s a wide range of behaviors in primitive societies and some form of private property is almost always present. The Open Society & Its Complexities - from last year’s book list - covers similar ground in great detail.

The author leaves us with the following quote:

“The popularity of the idea of primitive communism, especially in the face of contradictory evidence, tells us something important about why narratives succeed. Primitive communism may misrepresent forager societies. But it is simple, and it accords with widespread beliefs about the arc of human history. If we assume that societies went from small to big, or from egalitarian to despotic, then it makes sense that they transitioned from property-less harmony to selfish competition, too. Even if the facts of primitive communism are off, the story feels right…By drawing a contrast between an angelic past and our greedy present, primitive communism blinds us to the true determinants of trust, freedom and equity. If we want to build better societies, the way forward is neither to live as hunter-gatherers nor to bang the drum of a make-believe state of nature. Rather, it is to work with humans as they are, warts and all.”

Differentially Private Approximate Quantiles

Authors: Haim Kaplan, Shachar Schnapp, and Uri Stemmer

Publication: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning

Published: 2021

Link: Click here

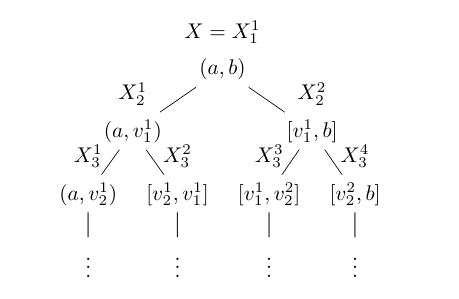

This paper presents a recursive schema for computing multiple differentially private quantile estimates. Given an ordered list of quantiles and a differentially private mechanism for computing a single quantile (they use this one from Adam Smith (2011) based on the exponential mechanism), this schema proceeds by first computing the middle quantile, then splitting the data domain into two sub-problems based on the middle quantile estimate, and repeating until all quantiles estimates are computed.

With differential privacy, each time an algorithm accesses the data to compute a value, measure error, and so forth, it incurs a privacy cost. An interesting property of differential privacy called parallel composition says that if an algorithm does the same operation on each member of a partitioned dataset, it only incurs the privacy cost once. So this schema only pays the privacy cost once each round.

Computationally, differentially private quantile algorithms typically scale with the size of the dataset. Since the data domain gets progressively divied up with each round, the quantile algorithms speed up each round.

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee